Beneficence in Nursing: Understanding Ethics, Nonmaleficence and the Principles of Clinical Ethics in Patient Care

In the complex environment of health-care delivery, nurses continually encounter decisions that reach beyond technical competence and into the domain of moral judgement. At the heart of such judgement lies a foundational ethical principle: the duty to act for the good of others. In nursing practice, this translates into the concept of beneficence in nursing, a guiding imperative for providing purposeful, compassionate nursing care that advances patient well-being while remaining attentive to the risk of harm. Indeed, beneficence and nonmaleficence—its close companion—form twin pillars of clinical ethics, requiring nursing professionals to deliver interventions which promote health and prevent injury.

For nursing students embarking on their professional journey, understanding the principle of beneficence becomes essential. It is not simply a theoretical construct; it is woven into every element of patient care, from everyday comfort measures to acute intervention decisions. Moreover, in the broader context of nursing ethics and health-care systems, the principle of beneficence requires careful alignment with patient autonomy, justice, and safety. In short, nurse decision-making demands more than doing what is clinically indicated—it demands doing what is ethically sound.

This article offers a comprehensive guide to the principle of beneficence as it applies in nursing: what it means, why it matters in nursing practice, how it relates to nonmaleficence, and how nurses can apply it in real-world situations. By exploring examples, discussing ethical dilemmas, and presenting strategies for sound ethical decision-making, the aim is to equip nursing students with a sharp and nuanced understanding of how beneficence operates in practice—and how they can uphold it in their future nursing roles.

What is Beneficence in Nursing Medical Ethics?

Beneficence in nursing ethics refers to the moral obligation of nurses to act in ways that promote the welfare and well-being of patients. It is a proactive ethical commitment: not merely avoiding harm, but taking deliberate steps to produce benefit—physically, psychologically, and socially—for those under a nurse’s care. In clinical ethics the concept anchors many everyday choices nurses make, from timely pain relief to advocating for community resources that address social determinants of health. This principle is embedded in nursing codes and standards that emphasize compassion, protection of safety, and advancement of patient well-being.

Core features nursing students should note

- Action-oriented duty. Beneficence is a duty to do good: intervene, prevent, or remove conditions that threaten a patient’s interests. This distinguishes it from duties that are primarily about not causing harm.

- Context sensitivity. What counts as “good” must be judged in light of clinical evidence, the patient’s values, and the situation (e.g., acute vs. palliative care).

- Relational scope. In nursing, beneficence often extends beyond clinical acts to relational and advocacy roles—comfort, education, and coordination of services that improve outcomes.

How is Beneficence Defined?

Philosophical and clinical bioethics sources commonly define beneficence as a moral requirement to promote good and prevent or remove harm. Textbooks and the “four principles” approach characterize it as one of four principal pillars (beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, justice) used to structure ethical analysis in health care. In applied nursing literature, scholars refine the definition by distinguishing:

- Positive beneficence (taking steps to produce benefit — e.g., performing an intervention expected to improve health); and

- Utility considerations (weighing the magnitude and likelihood of benefit against burdens or risks).

Clinical guidance emphasizes that beneficence must be evidence-informed (what actions reliably improve outcomes) and sensitive to patient preferences — otherwise, “doing good” risks becoming paternalistic or ethically problematic. Nursing scholarship calls for operational definitions that fit nursing care contexts (comfort care, education, advocacy) and for instruments that can measure how beneficence is applied across clinical settings.

Why is Beneficence Important in Nursing?

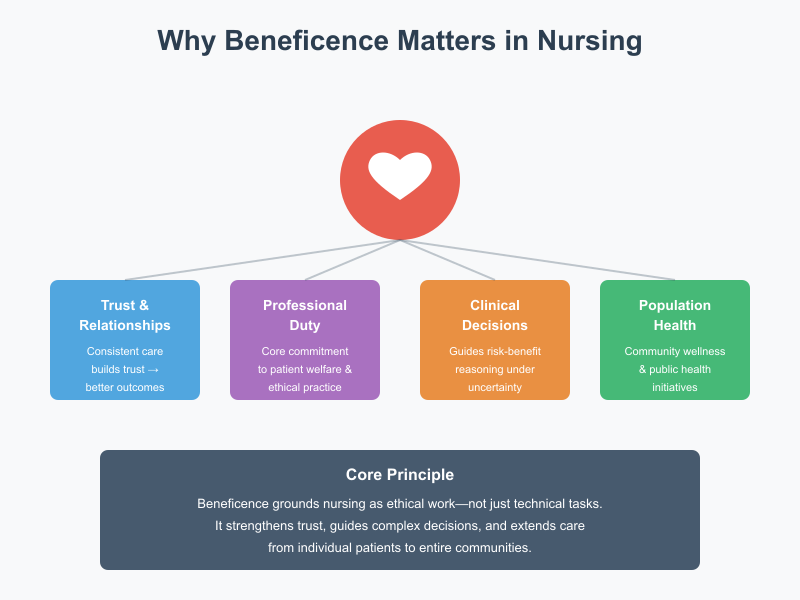

Beneficence is central to trust, professional identity, and clinical effectiveness:

- Trust and therapeutic relationship. When nurses consistently act to benefit patients, trust strengthens; patients are likelier to participate in care plans and share information essential to safe, effective care. (Trust → adherence → better outcomes).

- Professional imperative and duty of care. Nursing codes frame beneficence as part of the nurse’s primary commitment to patients. This grounds routine obligations—advocacy, pain management, safety interventions—as ethical work, not only technical tasks.

- Decision-making under uncertainty. Clinical situations often present trade-offs (e.g., aggressive treatment with potential benefit but significant risk). Beneficence provides an ethical touchstone for assessing expected benefits, guiding risk–benefit reasoning alongside other principles such as autonomy and justice.

- Population and systems level impact. Beneficence extends to public and community health efforts (e.g., vaccination campaigns, health education) where nurses act to promote collective welfare in addition to individual patient good.

What Are Examples of Beneficence in Practice?

Below are typical clinical and relational examples that illustrate how beneficence appears in everyday nursing practice. For each example I highlight what benefit is created, how the nurse acts, and ethical considerations.

- Pain assessment and management

- What: Reducing suffering and improving functionality.

- How: Regular pain assessments, timely analgesia, advocating for multimodal pain control and reassessment.

- Ethical note: Balancing benefit of pain relief against risks (sedation, respiratory depression) requires careful judgement and collaboration. (Example of beneficence that must be weighed with nonmaleficence.)

- Preventing falls and injuries

- What: Prevents harm, preserves independence.

- How: Implementing fall-risk screening, environmental safety checks, toileting schedules, and education for families.

- Ethical note: Measures should respect dignity and autonomy (e.g., avoiding unnecessary restraints). This is beneficence implemented with respect for autonomy.

- Patient education and discharge planning

- What: Promotes safe recovery and reduces readmissions.

- How: Teaching wound care, medication timing, red-flag symptoms, arranging community support.

- Ethical note: Education empowers patient autonomy while promoting benefit—an ethically integrative activity.

- Advocacy for social needs

- What: Addresses social determinants that affect health (transport, food security).

- How: Referrals to social work, community resources, coordinating care.

- Ethical note: Broadens beneficence from clinical interventions to social welfare acts that are essential to patient care.

- Compassionate presence and emotional support

- What: Reduces anxiety, fosters coping, enhances dignity.

- How: Active listening, validating concerns, supporting families during difficult conversations.

- Ethical note: Although non-procedural, these actions are ethically significant components of nursing care and core to the moral heart of the profession.

Beneficence Vs Nonmaleficence in Healthcare

In clinical ethics, beneficence and nonmaleficence are closely linked but distinct moral commitments. Beneficence directs clinicians to take positive steps to promote patient welfare — to “do good” — while nonmaleficence requires that clinicians avoid causing harm — to “do no harm.” Together they form complementary pillars of ethical practice: beneficence motivates action that benefits patients, and nonmaleficence constrains those actions by requiring attention to potential harms and risks. In nursing, this relationship shapes everyday decisions (e.g., treating pain vs. avoiding sedation-related respiratory depression), policy development (safety protocols), and professional identity (the nurse as both caregiver and protector of safety).

What is Nonmaleficence and Why Does it Matter in the Ethical Principles of Nursing?

Definition and core meaning. Nonmaleficence is the ethical obligation to avoid causing unnecessary harm or needless risk of harm to patients. Philosophically and in clinical guidance it is often stated simply as “do no harm,” but in practice it requires careful risk assessment, harm-minimization strategies, and humility about the limits of interventions. Where beneficence pushes for benefit, nonmaleficence pulls back to ensure benefits are not outweighed by preventable harms.

Why it matters in nursing practice.

- Patient safety and trust: Nonmaleficence underpins safety initiatives (infection control, medication checks, fall prevention) that protect patients from iatrogenic harm. Nursing actions designed around minimizing harm strengthen trust and therapeutic relationships.

- Clinical prudence: Nonmaleficence requires critical appraisal of interventions (is this procedure more likely to help than to injure?), prompting nurses to escalate concerns, seek second opinions, or delay interventions when risk is high.

- Ethical limits on action: Nonmaleficence sets moral boundaries that restrain even well-intended interventions — for instance, aggressive life-prolonging treatments that cause suffering may be ethically questionable if they produce more harm than benefit. This is especially salient in palliative and end-of-life care.

How Do Beneficence and Nonmaleficence Work Together in the Medical Field?

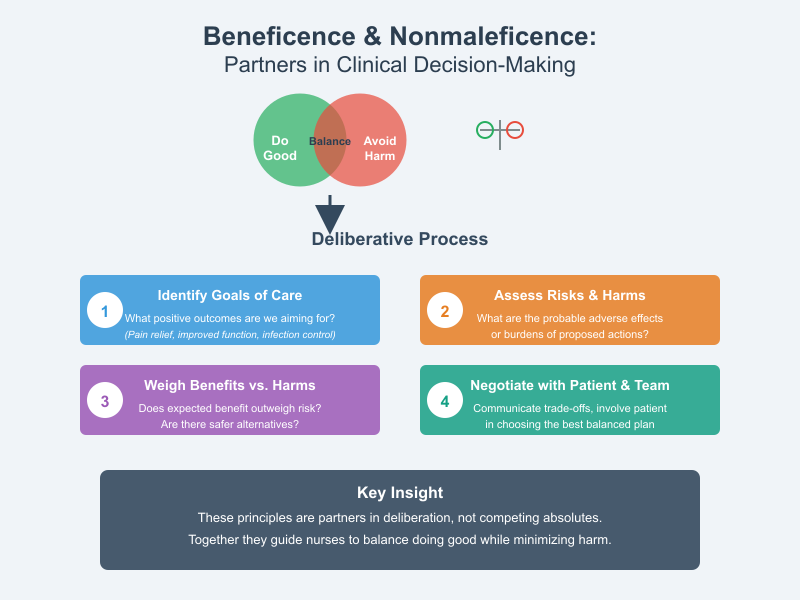

Beneficence and nonmaleficence are best seen as partners in a deliberative process rather than competing absolutes. In clinical decision-making nurses typically use both principles to:

- Identify goals of care (beneficence): What positive outcomes (pain relief, infection control, improved function) are we aiming for?

- Assess risks and harms (nonmaleficence): What are the probable adverse effects or burdens of proposed actions?

- Weigh benefits against harms (balancing): Does expected benefit sufficiently outweigh risk? Are there safer alternatives that preserve benefit with less harm?

- Negotiate with the patient (respect for autonomy) and team: Communicate trade-offs, document preferences, and involve the patient (or surrogate) in choosing the plan that best balances doing good and avoiding harm.

Framework example — analgesia in an elderly patient:

- Beneficence supports giving analgesics to relieve suffering and improve mobility.

- Nonmaleficence requires assessing fall risk and sedation: an opioid dose that controls pain but increases fall risk may be harmful.

- Working together means choosing multimodal pain relief, using the lowest effective dose, adding nonpharmacologic measures (ice, positioning), and monitoring closely — thereby maximizing benefit while minimizing harm. This process illustrates how the two principles guide concrete nursing actions.

Can Beneficence Conflict with Nonmaleficence in Nursing Practice?

Typical conflict scenarios. Conflicts arise when actions that promise benefit carry meaningful risk of harm. Common settings include:

- Aggressive treatments with severe side effects (e.g., chemotherapy in frail patients): potential for prolonged survival vs. high treatment burden and toxicity.

- Resuscitation decisions: Attempting CPR may offer possible survival but has high likelihood of poor outcome and suffering for some patients; the beneficent desire to save life must be tempered by nonmaleficence concerns.

- End-of-life interventions vs. comfort care: Life-prolonging interventions may conflict with goals of comfort, creating tension between doing good (preserving life) and preventing harm (avoiding undue suffering).

Strategies for resolving conflicts (practical steps for nursing students):

- Use structured ethical reasoning: Identify the benefits and harms clearly, consult the four-principles framework (beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, justice), and map possible outcomes.

- Prioritize patient values: If a competent patient refuses an intervention that could help, respect for autonomy may prevail — the nurse should explain benefits and harms but not coerce. If the patient lacks capacity, involve surrogates and apply best-interest standards.

- Seek interdisciplinary input: Discuss with physicians, palliative care, ethics committees, and family to ensure a balanced view of likely benefits and harms; nurses often bring vital bedside knowledge to these deliberations.

- Document rationale and monitoring plans: When proceeding with a risky but potentially beneficial action, document the reasoning, obtain informed consent if possible, set clear monitoring and stop criteria to minimize harms.

Case vignette (decision practice):

An 82-year-old patient with advanced heart failure is offered an invasive ventricular assist device that could extend life but carries high perioperative mortality and morbidity. The nurse must: explain risks and benefits (education), assess the patient’s goals (life extension vs. comfort), advocate for palliative consultation, and support shared decision-making. Here beneficence (prolong life) and nonmaleficence (avoid suffering) are balanced through patient-centered deliberation and interprofessional collaboration.

What Are the Ethical Implications of Beneficence in Nursing Ethics?

Beneficence in nursing is central to the ethical foundation of patient care. It represents the moral heart of the nursing profession, compelling nurses to act in ways that promote the best interest of their patients. The ethical principle of beneficence goes beyond simply avoiding harm; it embodies the nurse’s duty to actively do good — to provide care that enhances well-being, relieves suffering, and promotes healing. In this way, beneficence aligns with the principles of biomedical ethics and is closely related to nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice, which together form the four main ethical principles that guide nursing care and medical ethics.

The ethical implications of beneficence extend deeply into everyday nursing practice. Nurses must constantly balance the principle of beneficence with respect for patient autonomy and the principle of nonmaleficence — ensuring that actions taken to do good do not simultaneously cause harm or override a patient’s right to make independent choices. For instance, administering pain medication demonstrates beneficence by relieving suffering, but the nurse must also consider nonmaleficence by monitoring for potential side effects such as respiratory depression. In such cases, beneficence requires careful judgment, evidence-based decision-making, and continuous patient assessment.

Furthermore, beneficence has institutional implications for healthcare professionals and organizations. Upholding the ethical principles in nursing means designing policies and systems that encourage safe and compassionate care — such as implementing fall prevention programs, promoting infection control, and fostering communication that respects the patient’s emotional and cultural needs. The principle of beneficence therefore drives nurses and healthcare institutions to create environments that protect patients’ physical and psychological integrity while supporting their dignity and comfort.

How Do Nurses Make Ethical Decisions Involving Beneficence?

Ethical decision-making in nursing requires integrating clinical ethics and their application with compassionate judgment. Nurses frequently face complex decisions where the principles of beneficence and autonomy or beneficence and nonmaleficence may seem to conflict. To navigate such dilemmas, they often rely on structured ethical reasoning models such as the Four-Box Approach or the Principles of Clinical Ethics Framework developed by Beauchamp and Childress. These frameworks emphasize that ethical principles of nursing should be balanced rather than applied rigidly.

A practical example of beneficence-based decision-making occurs in end-of-life care. A nurse caring for a terminally ill patient may recommend palliative sedation to relieve unbearable pain. This act of beneficence aims to improve comfort but must be weighed against nonmaleficence, considering that sedation could shorten life. The nurse must also uphold patient autonomy by ensuring informed consent and discussing the patient’s preferences and values. Ethical decision-making, therefore, is not a simple algorithm but a reflective process that blends empathy, moral reasoning, and professional responsibility.

Another example is when a nurse advocates for a patient’s need for mental health support after a traumatic diagnosis. Beneficence requires that the nurse go beyond routine clinical tasks and demonstrate beneficence by advocating for psychological care, promoting communication between the patient and care team, and connecting the patient to counseling services. Here, beneficence in practice involves both direct clinical interventions and moral advocacy — showing how nursing ethics is inseparable from compassion and advocacy.

In every care setting, nurses apply beneficence by making daily micro-decisions: repositioning patients to prevent pressure ulcers, providing emotional support during procedures, and ensuring that patients understand treatment options. Each decision reflects beneficence as a core principle in medical ethics — the commitment to enhance health and well-being through knowledge, empathy, and moral integrity.

What Role Does Patient Autonomy Play in Beneficence?

The interplay between beneficence and autonomy is one of the most important aspects of health care ethics. While beneficence motivates nurses to act for the patient’s welfare, autonomy asserts the patient’s right to self-determination — to make choices about their own medical care. The principle of patient autonomy is grounded in respect for human dignity and the belief that patients are moral agents capable of making informed decisions about their health.

Sometimes, beneficence and autonomy collide when a nurse believes that an intervention is in the patient’s best interest, but the patient refuses it. For example, a diabetic patient may decline insulin therapy because of fear or cultural beliefs. The nurse, guided by beneficence, might feel obligated to persuade the patient to accept the treatment, but ethical practice requires respecting the patient’s choice. In such cases, balancing beneficence involves engaging in empathetic dialogue, providing education, and exploring underlying reasons for refusal rather than overriding autonomy.

Beneficence and respect for autonomy must therefore coexist. A nurse shows beneficence by respecting a patient’s values and choices, even when those choices differ from clinical recommendations. This respect is a form of care ethics — recognizing that beneficence is not only about actions that improve health outcomes but also about fostering trust, empathy, and human connection in nursing and medical practice. The ethical obligation is to support the patient’s informed decision-making process, ensuring that their choices are respected without judgment while continuing to advocate for their welfare.

How Can Ethical Dilemmas Arise from the Principle of Beneficence?

Ethical dilemmas frequently arise when applying the principle of beneficence, especially when competing ethical values are at stake. One common dilemma involves conflicts between beneficence and nonmaleficence, such as when a potentially beneficial treatment poses significant risk. For instance, a nurse may face a decision about whether to continue an aggressive chemotherapy regimen that offers marginal benefit but causes severe side effects. Acting beneficently means promoting healing, yet beneficence may conflict with the duty to avoid harm.

Another dilemma occurs when beneficence conflicts with patient autonomy. A nurse may believe that a treatment or procedure is in the patient’s best interest, but the patient’s personal values or cultural beliefs lead them to decline it. This tension forces nurses to navigate the line between advocating for the patient’s welfare and respecting their right to make autonomous decisions.

Ethical dilemmas can also arise from institutional or systemic constraints. Limited resources, staffing shortages, or policy restrictions may prevent nurses from providing the level of care they believe beneficence requires. In these cases, beneficence in health care becomes a matter of ethical advocacy — where nurses must raise concerns, seek institutional support, and push for systemic changes that uphold patient welfare.

To manage these dilemmas, nurses often engage in ethical reflection and consult interdisciplinary teams, including ethics committees. By integrating the principles of beneficence and autonomy with clinical ethics and their application, nurses can arrive at decisions that are morally sound and patient-centered.

Ultimately, understanding and applying the ethical principle of beneficence helps nurses navigate the moral complexities of nursing practice. It encourages compassion guided by critical thinking and professional accountability. Beneficence is not merely an abstract ethical concept; it is a living standard that shapes every decision a nurse makes — from the smallest act of kindness to complex clinical interventions.

How Can Nurses Promote Fundamental Principle of Beneficence in Their Practice?

Promoting beneficence in nursing practice involves a conscious commitment to acting in the best interest of the patient at all times. In nursing ethics, beneficence is defined as the obligation to “do good,” which extends beyond merely avoiding harm. It requires nurses to engage in deliberate acts of kindness, compassion, and professional responsibility. The ethical principle of beneficence obliges nurses to provide care that enhances the patient’s well-being, promotes healing, and alleviates suffering.

In day-to-day patient care, beneficence manifests in several ways. A nurse who ensures timely administration of pain medication, provides emotional reassurance to a distressed patient, or advocates for improved discharge planning demonstrates beneficence. Likewise, preventing pressure injuries by frequent repositioning of immobile patients shows proactive beneficence—it reflects a deliberate act to enhance health outcomes.

The principle of beneficence also applies at the organizational and community levels. Nurses promote beneficence when they engage in health education programs, participate in infection control initiatives, or contribute to policies that protect vulnerable populations. Each of these actions serves a collective form of beneficence in healthcare, reinforcing the ethical obligation to improve public health outcomes while upholding professional integrity.

Beneficence is inseparable from nursing practice and the broader framework of medical ethics. It demands not only technical proficiency but also moral reasoning and empathy. By integrating the principles of clinical ethics—beneficence, nonmaleficence, justice, and autonomy—nurses ensure that every clinical decision is grounded in ethical reflection and patient-centered care.

What Strategies Can Nurses Implement to Uphold Beneficence?

Upholding beneficence in nursing requires intentional strategies that support ethical decision-making and consistent delivery of high-quality nursing care. The following approaches help nurses ensure that their actions conform to the ethical principles of nursing:

- Engage in Evidence-Based Practice:

Beneficence demands that care decisions are informed by the best available evidence. Using clinical guidelines, research findings, and institutional protocols ensures that patient interventions produce genuine benefit and minimize risk. For instance, evidence-based fall prevention programs demonstrate both beneficence and nonmaleficence, as they aim to prevent harm while promoting safety. - Practice Ethical Reflection and Moral Reasoning:

Nurses must continuously reflect on whether their actions serve the patient’s best interest. Ethical reflection involves considering whether an intervention aligns with the principle of beneficence, patient autonomy, and clinical ethics. Participating in ethics rounds or discussing complex cases with peers helps nurses navigate moral uncertainty, particularly in situations where beneficence may conflict with other ethical principles. - Advocate for Patients:

Advocacy is a direct expression of beneficence in nursing. When systemic barriers or policy limitations affect patient outcomes, nurses demonstrate beneficence by speaking up on behalf of those under their care. For example, advocating for equitable access to medication or safe staffing levels ensures that patients receive optimal medical care, aligning with the principles of beneficence and justice within biomedical ethics. - Maintain Cultural Sensitivity and Empathy:

Beneficence in health care ethics requires nurses to recognize the cultural, spiritual, and personal values of each patient. What constitutes “doing good” may differ across cultures. Providing care that respects diversity reflects both beneficence and respect for autonomy. - Foster Interprofessional Collaboration:

Beneficence flourishes in a collaborative environment. Effective teamwork among healthcare professionals enhances safety, accuracy, and holistic care. Working closely with physicians, social workers, and therapists ensures that beneficence and nonmaleficence are achieved through comprehensive planning and mutual accountability. - Commit to Lifelong Learning:

Beneficence requires continuous professional growth. Nurses must stay informed about evolving standards of practice, emerging technologies, and new ethical frameworks. A nurse who continually refines clinical competence demonstrates the ethical commitment to take positive action for the good of others—a core aspect of beneficence.

How Can Effective Communication Enhance Beneficence?

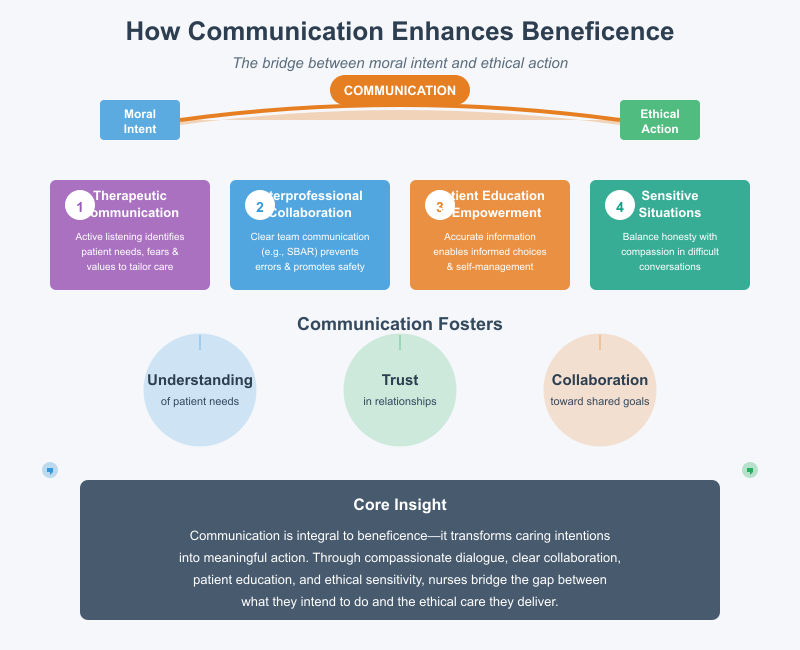

Effective communication is integral to beneficence because it fosters understanding, trust, and collaboration—key elements of ethical patient care. In the context of nursing ethics and medical ethics, communication serves as the bridge between moral intent and ethical action.

- Therapeutic Communication with Patients:

Compassionate and active listening allows nurses to identify patients’ physical and emotional needs accurately. By understanding a patient’s fears, preferences, or values, the nurse can tailor interventions that truly reflect beneficence. For example, listening to a terminally ill patient’s concerns and ensuring their comfort through palliative measures demonstrates beneficence aligned with nonmaleficence—doing good while avoiding unnecessary suffering. - Clear Interprofessional Communication:

Collaboration among healthcare professionals is essential to uphold beneficence. Poor communication can result in medical errors that violate nonmaleficence. Using structured tools such as SBAR (Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation) ensures that patient information is communicated clearly and accurately, promoting safety and continuity of care. - Educating and Empowering Patients:

Education is a form of beneficence. By providing accurate, understandable information, nurses enable patients to make informed decisions consistent with their personal values. This fosters respect for patient autonomy while upholding the principle of beneficence. For instance, educating a diabetic patient on proper nutrition and insulin use enhances self-management and long-term wellness. - Ethical Communication in Sensitive Situations:

In emotionally charged circumstances—such as end-of-life discussions, withdrawal of treatment, or disclosure of a poor prognosis—communication must balance honesty with compassion. Beneficence requires that nurses communicate truthfully while minimizing distress, demonstrating respect for the patient’s dignity and emotional well-being.

Effective communication thus transforms beneficence from an abstract moral concept into a lived ethical practice. It ensures that beneficence and nonmaleficence coexist harmoniously, guiding both verbal and nonverbal interactions toward compassionate, patient-centered outcomes.

Conclusion

In summary, beneficence in nursing ethics stands as a guiding moral principle that compels nurses to act in ways that promote the well-being, health, and safety of patients. It is the heart of ethical nursing practice, ensuring that every decision and action taken by nurses is motivated by the intent to do good and enhance patient outcomes. Beneficence goes beyond simply avoiding harm—it requires proactive engagement in acts of kindness, compassion, and clinical excellence.

The principle of beneficence is inseparable from nonmaleficence, as both work together to balance the duty to do good with the obligation to avoid harm. However, in some situations, nurses face ethical dilemmas where the application of beneficence conflicts with patient autonomy or clinical realities. For instance, continuing aggressive treatment for a terminally ill patient may seem beneficent, but it may also prolong suffering, thereby violating nonmaleficence. Navigating such conflicts requires nurses to use sound ethical judgment, empathy, and critical thinking grounded in nursing ethics and medical ethics frameworks.

To promote beneficence in nursing, nurses must uphold professional standards, engage in patient advocacy, and foster open, compassionate communication with patients and families. This ensures that care decisions reflect patients’ values and preferences while achieving the highest level of ethical care. Continuous education, reflective practice, and collaboration with interdisciplinary teams further strengthen nurses’ ability to apply beneficence effectively in diverse care settings.

Ultimately, beneficence embodies the essence of nursing—the moral commitment to prioritize human dignity, health, and compassion. When nurses integrate beneficence into every aspect of care, they not only fulfill their ethical duty but also uphold the trust society places in the nursing profession as a cornerstone of ethical and humane healthcare.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the ethical principles of beneficence and non-maleficence?

The ethical principles of beneficence and non-maleficence are foundational in nursing ethics. Beneficence requires nurses to act in the best interest of patients by promoting well-being and preventing harm, while non-maleficence means avoiding actions that could cause injury or suffering. Together, they ensure that nurses balance doing good with preventing harm in all aspects of patient care.

What is the principle of beneficence in nursing?

The principle of beneficence in nursing emphasizes the moral obligation to help patients, promote healing, and enhance quality of life. It guides nurses to provide compassionate, evidence-based care that improves patient outcomes and supports physical, emotional, and psychological well-being.

What is the role of the nurse in non-maleficence?

The nurse’s role in non-maleficence is to ensure patient safety by avoiding harm through careful practice, adherence to clinical standards, and vigilant monitoring. This includes preventing medication errors, minimizing patient discomfort, and advocating against unnecessary or harmful interventions.

What is an example of beneficence and non-maleficence in nursing?

An example of beneficence and non-maleficence in nursing is when a nurse administers pain medication to relieve a patient’s suffering (beneficence) while carefully monitoring the dosage to avoid potential overdose or side effects (non-maleficence). This balance reflects ethical decision-making that prioritizes both compassion and safety.