Wound Healing Stages: Understanding the Four Stages of Wound Healing

Introduction to Wound Healing and Its Importance

Wound healing is a fundamental biological process that restores skin integrity and tissue function following injury. In clinical practice, understanding the stages of wound healing is essential for nurses, as it provides a structured framework to assess wounds, anticipate complications, and implement appropriate interventions. A wound, whether acute or chronic, triggers a complex sequence of cellular and molecular events designed to close the injury, rebuild tissue, and restore the skin’s protective barrier.

The wound healing process is highly coordinated, involving a series of overlapping phases, each with distinct cellular activities and clinical characteristics. Platelets, white blood cells, and growth factors orchestrate the early response, while epithelial cells, fibroblasts, and collagen deposition dominate the later stages of tissue repair. By recognizing the nuances of each stage of healing, nurses can identify deviations from normal progress, such as delayed healing, poor wound healing, or wound infection, and adjust wound care strategies accordingly.

In addition to facilitating clinical assessment, knowledge of the four stages of wound healing equips nurses to optimize patient outcomes. From the initial inflammatory phase to the proliferative and remodeling phases, each stage requires tailored interventions to support angiogenesis, granulation tissue formation, and eventual wound closure. Proper wound care, including monitoring the wound bed, edges of the wound, and overall wound site, ensures that the healing process progresses efficiently while minimizing complications such as excessive scarring or chronic wound development.

Furthermore, the significance of wound healing extends beyond individual patient care. It informs nursing decision-making regarding chronic wound management, advanced wound care interventions, and at-home wound care instructions for patients recovering outside the hospital setting. Understanding the four stages of wound healing also allows nurses to anticipate the natural timeline of recovery, recognize signs of abnormal healing, and integrate evidence-based strategies that promote proper wound healing and tissue repair.

This article offers a comprehensive exploration of wound healing stages, highlighting the biological mechanisms, clinical implications, and practical considerations for nursing practice. By following a structured approach to the wound healing process, nursing students and practicing clinicians can enhance their understanding of wound assessment, implement effective wound care, and contribute to optimal healing and repair in diverse patient populations.

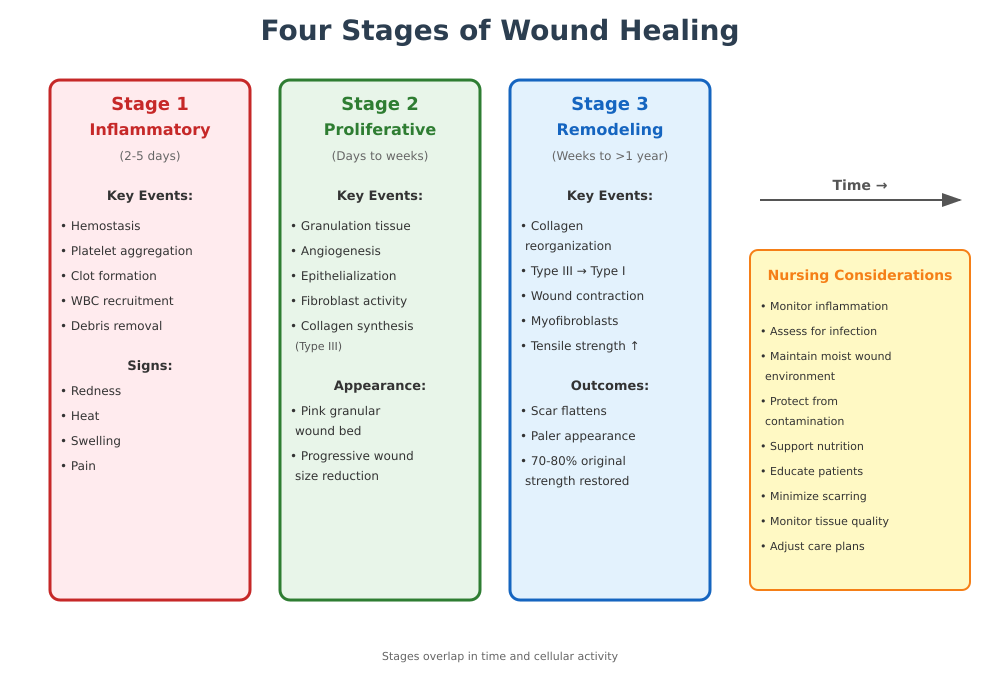

The Four Stages of Wound Healing

The body repairs an injury through a highly coordinated sequence of biological events, traditionally described as four stages of wound healing—hemostasis, inflammatory, proliferative, and remodeling. These stages overlap in time and cellular activity but each has definable characteristics nurses must recognize to support proper wound care and optimal tissue recovery.

Hemostasis and Inflammatory Phase

Explanation of the Inflammatory Phase as the First Stage of Wound Healing

Immediately following injury, the first concern for the body is to stop bleeding and prevent microbial invasion. This initiates the inflammatory phase, beginning concurrently with hemostasis, the mechanism that brings bleeding under control through vascular responses and clot formation.

Role of Platelets, White Blood Cells, and Clot Formation

Platelets are among the first responders at an injury site. They aggregate and release chemical mediators that trigger clot formation, creating a temporary matrix composed of fibrin and cellular debris that stabilizes the wound and provides a scaffold for cellular migration. These mediators include growth factors that attract white blood cells to the wound site, where they phagocytose debris and pathogens—this decontamination is central to establishing a clean field for repair.

Duration of the Inflammatory Phase

The inflammatory phase typically lasts around 2 to 5 days after injury, though this timeline can vary depending on individual health and wound severity. During this period, vasodilation increases blood flow to the wound area, facilitating immune cell recruitment and nutrient delivery.

Signs of Normal Inflammation vs. Early Wound Infection

Normal inflammation is marked by redness, heat, swelling, and pain—reflecting increased blood flow and immune activity. A wound that continues to be excessively warm, painful, or producing purulent discharge beyond the expected inflammatory period may signal wound infection, requiring timely clinical assessment.

Proliferative Phase

The proliferative phase succeeds the inflammatory stage and is characterized by substantial tissue rebuilding. This stage may begin within days of injury and continues for several weeks.

Key Events: Granulation Tissue Formation, Epithelialization, Angiogenesis

During this stage, granulation tissue forms in the wound bed as new capillaries sprout through angiogenesis, ensuring an adequate blood supply. Epithelial cells migrate from the wound edges to resurface the wound, gradually restoring the skin barrier. These processes are interdependent: a robust capillary network enhances nutrient delivery, promoting surface coverage and wound closure.

Role of Fibroblasts and Collagen Deposition

Fibroblasts are dominant cellular players in this stage; they synthesize collagen, a critical structural protein that provides strength and support for the developing tissue. Initially, type III collagen predominates, later replaced by stronger type I collagen as healing progresses.

Importance of Proper Wound Care During This Phase

Appropriate wound care during proliferation includes keeping the wound surface moist but not macerated, protecting against contamination, and supporting capillary growth. Environmental conditions influence cellular activity; for example, maintaining an oxygen-rich environment supports collagen synthesis and angiogenesis.

Identifying Normal vs. Abnormal Proliferation

Normal proliferation produces a pink, granular wound bed with progressive reduction in wound size. Conversely, signs such as slow healing, an uneven or poor-quality tissue bed, or persistent wound infection suggest impaired progression and may require intervention.

Remodeling (Maturation) Phase

The remodeling phase is the final stage of the healing cascade and may last from several weeks to over a year, depending on the original wound’s size and severity.

Process of Collagen Remodeling and Wound Contraction

During remodeling, collagen fibers reorganize into a more orderly structure, replacing type III collagen with stronger type I. Wound contraction—driven by specialized cells called myofibroblasts—reduces the wound’s overall dimensions. Tensile strength increases over time, though the healed tissue typically regains only about 70–80% of the pre-injury strength.

Duration and Characteristics of the Remodel Phase

This phase begins around three weeks post-injury and can continue for months. The scar gradually becomes flatter and paler as excess capillaries regress and collagen fibers align along tension lines.

Strategies to Minimize Scarring and Improve Healed Tissue Appearance

Approaches such as gentle mobilization, pressure therapy, and ensuring adequate nutrition during remodeling may support optimal collagen organization and reduce excessive scar tissue. Nursing strategies that protect the wound from undue tension also contribute positively.

Role of Nursing Interventions in Supporting Tissue Strength and Wound Remodeling

Nurses monitor progress, educate patients on protecting healing tissue, and adjust care plans to support collagen realignment. Recognizing when a wound appears hypertrophic or keloid can prompt discussions about specialized referral or therapeutic options.

Identifying and Managing Wound Complications

Understanding how to recognize and manage complications during healing stages is essential for nursing practice. When the process of wound healing deviates from expected patterns, clinicians must distinguish between normal responses and signs that indicate problems such as wound infection or poor wound healing. This section explores how to assess complications, underlying factors that affect wound healing, and strategies for managing chronic wound conditions and acute injuries that fail to progress through appropriate healing phases.

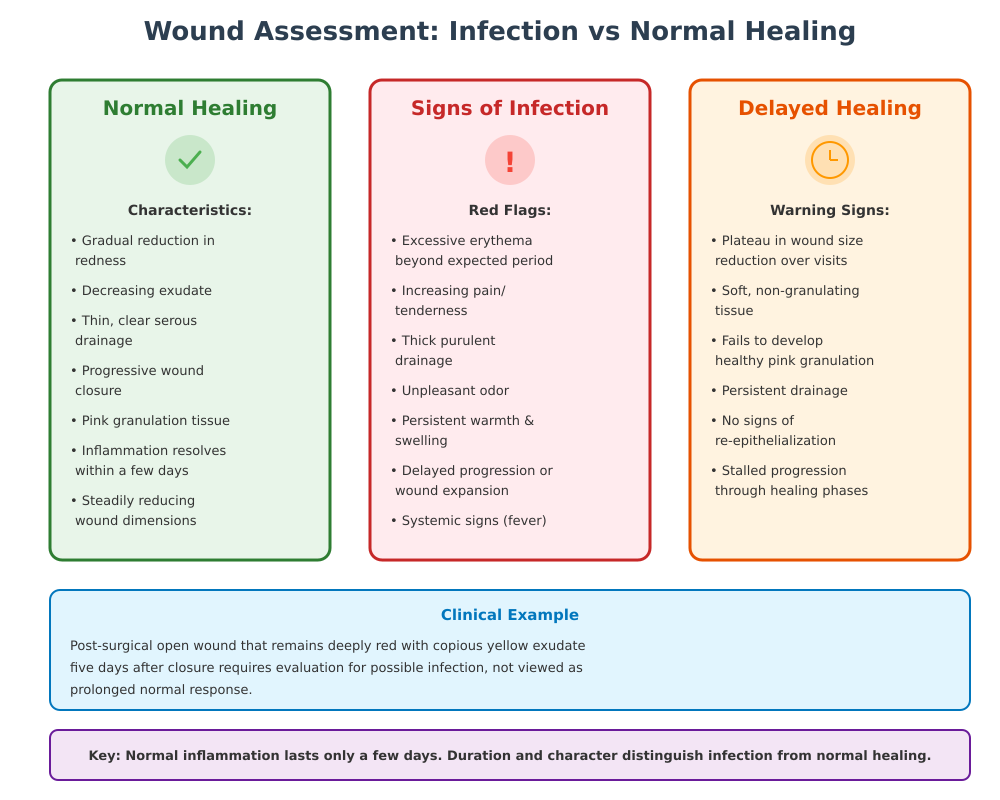

Recognizing Wound Infection and Delayed Healing

After initial injury, it is expected that the wound bed and surrounding skin will exhibit some degree of redness and warmth as part of inflammation. However, prolonged or worsening changes may indicate pathological infection rather than a normal immune response.

Signs of Wound Infection

A normal wound typically shows a gradual reduction in redness and exudate as healing progresses. In contrast, signs of wound infection may include:

- Wound edges that appear excessively erythematous or inflamed beyond the expected inflammatory period.

- Increasing pain or tenderness at the wound site that is disproportionate to what is typical for the healing stages.

- Thick, purulent drainage with an unpleasant odor from the wound bed, which differs from the thin, clear serous fluid seen in uncomplicated healing.

- Localized swelling and delayed progression toward wound closure or even wound expansion rather than contraction.

For example, a post-surgical open wound that remains deeply red with copious yellow exudate five days after closure requires evaluation for possible infection rather than being viewed as a prolonged normal response.

Infection vs. Normal Inflammatory Response

Clinicians distinguish a pathological infection from normal inflammatory activity by duration and character. The inflammatory phase of healing is expected to last only a few days; persistent warmth, swelling, and systemic signs such as fever indicate that the body may be struggling with microbial colonization rather than resolving tissue injury.

Recognizing Delayed Healing

Delayed healing or poor wound healing manifests when tissue repair stalls and the wound fails to progress through the expected healing phases. Indications include:

- Plateau in reduction of wound dimensions over several clinic visits.

- Soft, non-granulating wound tissue that fails to develop healthy pink granulation.

- Persistent drainage without signs of re‐epithelialization.

Factors Affecting Wound Healing

Multiple systemic and local factors can affect wound healing, making some patients more susceptible to complications.

Chronic Conditions and Poor Blood Flow

Conditions like peripheral vascular disease impair blood flow, reducing oxygen and nutrient delivery critical for cellular activity in healing. For patients with diabetes, compromised perfusion and neuropathy contribute to ulcers that linger and progress to chronic wounds, especially on lower extremities.

Nutrition, Systemic Diseases, Growth Factor Levels

Adequate protein and micronutrients such as zinc and vitamin C are essential for collagen synthesis and cellular proliferation. Insufficient dietary intake or metabolic disorders can diminish growth factor production and fibroblast function, stalling repair processes.

Medications and Comorbidities

Medications such as corticosteroids suppress immune function, affecting inflammatory cell recruitment and collagen deposition. Comorbidities like renal failure or immunosuppression further predispose patients to pathological healing responses.

Acute vs. Chronic Wounds

Understanding the distinction between acute wounds and those that become chronic is essential for targeted intervention.

When a Wound Is Considered Chronic

A wound that fails to move through timely healing stages or shows minimal measurable closure over several weeks (commonly 4–6 weeks) is often classified as a chronic wound. These injuries remain in a prolonged inflammatory state without adequate progression into the reconstructive phases, making them prone to recurrent infection and tissue breakdown.

Early Recognition of Acute Wounds Turning Chronic

Early indicators that an acute injury may be transitioning toward chronicity include stalled granulation formation, persistent pain, and repeated signs of inflammation without forward progression. For instance, a traumatic skin wound that shows minimal granulation after two clinic visits may require reevaluation of underlying causes such as ischemia or repetitive trauma.

Wound Care Strategies Across Healing Phases

Effective wound care requires a thorough understanding of the biological and clinical requirements at each phase of wound healing. Nursing interventions must be tailored to the specific stage of healing, whether managing an acute wound, preventing complications, or optimizing tissue strength during the remodeling phase. Proper care supports the healing process, reduces the risk of wound infection, and promotes optimal restoration of skin integrity.

Immediate Wound Care

The earliest interventions after an injury focus on stabilization, contamination prevention, and support for the body’s intrinsic repair mechanisms.

First Aid and Wound Protection

Immediately after injury, the wound site must be assessed, cleaned, and protected. Gentle irrigation with sterile saline removes debris while preserving wound tissue. Covering the wound bed with a sterile dressing minimizes the risk of contamination and protects the wound edges from mechanical trauma. For example, in a superficial skin wound caused by a laceration, applying a non-adherent dressing and securing it properly prevents reopening and supports wound closure.

Promoting Clot Formation and Preventing Infection

During the first stage of wound healing, platelets aggregate at the wound area, forming a clot that stabilizes the injury. Nursing strategies such as gentle compression and elevation help maintain hemostasis and blood flow, supporting proper wound healing. Antiseptic measures, including hand hygiene and careful dressing changes, prevent microbial colonization that could lead to an infected wound, compromising the healing and repair process.

Care During Proliferation

The proliferative phase is marked by the formation of granulation tissue, epithelial cells migration, and angiogenesis—the growth of new blood vessels to support tissue regeneration. Nursing interventions during this phase are critical to maintain an environment conducive to cellular proliferation and extracellular matrix formation.

Supporting Angiogenesis and Collagen Deposition

Adequate perfusion is essential to promote blood flow to the wound bed, delivering oxygen and nutrients that facilitate fibroblast activity and collagen synthesis. For instance, in a post-surgical skin wound, maintaining mild compression without restricting circulation can optimize wound tissue oxygenation, accelerating healing stages.

Maintaining a Moist Environment to Optimize Healing

Moist wound environments support skin cells migration across the wound edges, enhancing wound repair and reducing the risk of scab formation that can slow epithelialization. Modern wound care dressings—such as hydrocolloids or foam dressings—maintain moisture, protect the wound bed, and allow exudate management without disrupting the delicate new tissue forming in the wound site.

Care During Remodeling

The final phase of wound healing focuses on strengthening tissue, reorganizing collagen, and minimizing scar formation. Although the wound may appear superficially healed, active remodeling continues for weeks to months.

Reducing Scar Formation and Improving Cosmetic Outcomes

During remodel, collagen fibers align along lines of tension, contributing to wound contraction and tissue strength. Nursing strategies include supporting wound management techniques that minimize excessive strain on the wound edges. Topical silicone gels, massage therapy, and controlled tension through bandaging can reduce hypertrophic scarring and promote smoother new skin formation.

Pressure Management and Protective Measures

Protecting the wound area from repetitive stress, friction, or shearing forces is essential. For example, patients recovering from pressure ulcers benefit from frequent repositioning and use of pressure-relieving devices to maintain skin integrity and prevent delayed wound healing. Nurses also monitor for slow healing and intervene promptly if signs of wound infection appear, ensuring that the healing process progresses efficiently toward healed wound status.

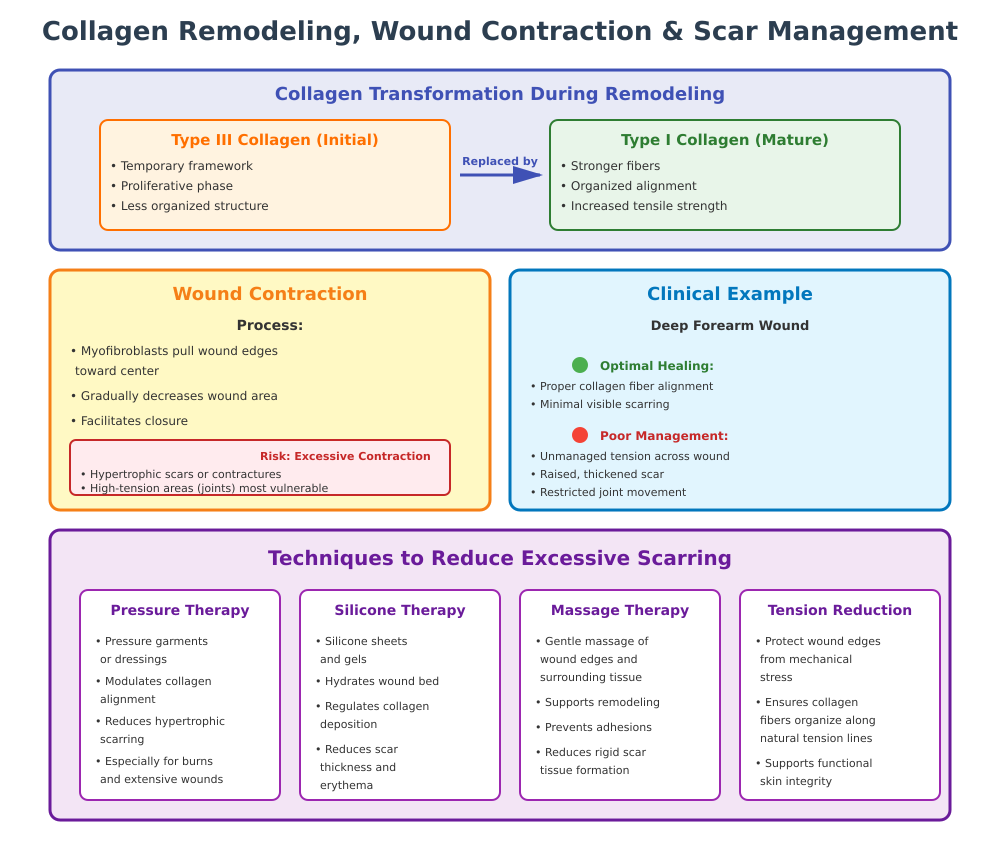

Scar Formation and Tissue Repair

The final stages of wound healing culminate in scar formation and tissue restoration, where the body remodels the wound tissue to regain structural integrity and skin function. Understanding the interplay between collagen deposition, wound contraction, and scar formation is essential for nurses to implement interventions that support effective healing and repair, minimize complications, and improve the long-term appearance of the healed wound.

Relationship Between Collagen Deposition, Wound Contraction, and Scar

During the remodeling phase of healing, fibroblasts actively replace temporary collagen laid down in the proliferative stage with more organized, stronger fibers. Initially, type III collagen provides a framework for tissue repair, but over time it is replaced by type I collagen, which increases tensile strength and contributes to wound contraction.

Wound contraction is the process by which the wound area gradually decreases in size as myofibroblasts pull the wound edges toward the center. While contraction is beneficial for reducing wound size and facilitating closure, excessive contraction can contribute to hypertrophic scars or contractures, especially in areas with high tension or mobility, such as joints.

For example, a deep skin wound on the forearm may heal with minimal visible scarring if collagen fibers align properly during remodeling. However, if tension across the wound site is not managed, the resulting scar may be raised, thickened, or restrict joint movement. Understanding this biological relationship allows nurses to anticipate areas at risk for poor wound repair and tailor interventions accordingly.

Techniques to Reduce Excessive Scarring

Several strategies can minimize abnormal scar formation and optimize tissue quality:

- Pressure Therapy: Application of pressure garments or dressings can modulate collagen alignment and reduce hypertrophic scarring, especially in burn wounds or extensive cutaneous wounds.

- Silicone Sheets and Gels: These materials hydrate the wound bed and regulate collagen deposition, reducing scar thickness and erythema.

- Massage Therapy: Gentle massaging of the wound edges and surrounding tissue supports remodeling and prevents adhesions or rigid scar tissue formation.

- Tension Reduction: Protecting wound edges from excessive mechanical stress during the remodeling phase ensures that collagen fibers organize along natural tension lines, supporting functional skin integrity.

For example, a patient recovering from an abdominal incision may be instructed to perform gentle scar massage once the wound is clean and epithelialized, while avoiding strenuous movements that stretch the healing tissue. These techniques, combined with careful monitoring, reduce the risk of pronounced scar development and improve cosmetic outcomes.

Role of Wound Care in Optimal Healing and Repair

Proper wound care throughout all healing phases directly influences scar formation and tissue strength. Early-stage interventions that reduce infection risk, maintain a moist wound bed, and support granulation tissue development set the stage for effective remodeling. During proliferation, protecting epithelial cells and supporting collagen synthesis ensures that the new tissue forms in a structured manner.

Nurses play a critical role in ongoing wound management by:

- Monitoring wound edges for abnormal thickening or delayed epithelialization.

- Educating patients on protective measures to avoid trauma to the wound site.

- Adjusting dressings to optimize moisture balance without maceration.

- Recognizing early signs of poor wound healing that may predispose to excessive or irregular scar formation.

Effective wound care not only promotes timely wound closure but also improves the quality of the healed wound, maintaining both functional and aesthetic skin integrity.

Conclusion

Understanding the wound healing stages is fundamental for nursing practice, providing a structured framework for assessing, managing, and supporting patients with both acute wounds and chronic wounds. From the initial inflammatory phase, where platelets and white blood cells orchestrate clot formation and early immune defense, through the proliferative phase, characterized by granulation tissue, angiogenesis, and collagen deposition, to the final remodeling phase, where tissue strengthens and scar formation occurs, each phase of wound healing has distinct clinical and biological implications.

Effective wound care requires an appreciation of these dynamic processes. By monitoring the wound bed, wound edges, and overall wound site, nurses can identify deviations such as wound infection, delayed healing, or excessive wound contraction, and implement timely interventions. Strategies tailored to each stage—ranging from immediate protection and promoting clot formation to supporting epithelial cells migration, collagen organization, and proper wound management during remodeling—ensure optimal tissue repair and functional skin integrity.

Additionally, recognizing factors that affect wound healing, including systemic diseases, nutritional status, and blood flow, allows nurses to individualize care plans and anticipate potential complications. In chronic or complicated wounds, early identification and evidence-based advanced wound care interventions can prevent further tissue damage and facilitate effective healing.

Ultimately, mastery of wound healing stages empowers nurses to provide comprehensive, patient-centered care, guiding the healing process from initial injury through to healed wound with minimal complications and optimal functional and aesthetic outcomes. By integrating scientific understanding with clinical vigilance and proper wound care strategies, nursing professionals can enhance recovery, promote wound repair, and improve the overall quality of patient care.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the 4 stages of wound healing?

The four stages of wound healing are:

- Hemostasis (first stage) – clot formation to stop bleeding.

- Inflammatory phase – immune cells like white blood cells clean the wound and prevent infection.

- Proliferative phase – granulation tissue forms, epithelial cells migrate, and collagen is deposited to rebuild tissue.

- Remodeling (maturation) phase – collagen is reorganized, wound contraction occurs, and the scar forms as tissue strengthens.

How do you know if a wound is healing properly?

A properly healing wound shows:

- Gradual reduction in wound size

- Healthy pink wound tissue and granulation tissue

- Minimal drainage that is clear or serous

- Edges slowly closing without excessive redness or swelling

What color is a healing wound?

- Healthy healing wounds are usually pink to red, indicating good blood flow and new tissue formation.

- Yellow may indicate slough, while black can signal necrosis, requiring intervention.

What are the 4 C’s of wound care?

The 4 C’s of wound care are:

- Clean – keep the wound clean to prevent infection.

- Cover – protect the wound bed and edges of the wound.

- Control – manage exudate and maintain a moist environment.

- Change – regularly replace dressings and assess healing progress.