Sample Statement of the Problem in Research: How to Write a Strong Problem Statement

Every successful research project begins with a clear understanding of what needs to be examined, explained, or improved. At the center of this process is the problem statement—a focused description of the issue that the study aims to address. Whether you’re working on a research paper, research proposal, or full research study, the statement of the problem defines the direction of your investigation and helps you stay aligned with your goals.

A strong problem statement in research is more than a simple declaration of what’s wrong; it explains why the issue matters, identifies what is missing in existing research, and describes how your study can contribute to solving it. In this sense, it acts as the foundation for the entire research process, linking the purpose of your study to clear research objectives and methods.

Imagine, for example, a research problem exploring the lack of digital literacy among nursing students. Without a precise statement of the problem, the study might wander aimlessly through general discussions of technology in education. But when you take time to write a problem statement that pinpoints the gap—such as the limited integration of online learning platforms in nursing programs—it becomes easier to design focused questions, select methods, and produce meaningful results.

Throughout this article, you’ll learn how to identify a specific problem, structure a clear and concise statement, and develop the confidence to craft a problem statement that strengthens your research writing. You’ll also find practical examples and insights that show how a well-defined problem leads to more effective and impactful research. Ultimately, understanding the purpose and function of a problem statement is key to producing good research that contributes real value to your field.

What is a Sample Statement of the Problem in Research?

A statement of the problem is a short, focused declaration that explains the gap, difficulty, or need your research intends to address. It goes beyond simply naming a topic: it locates a specific issue within an area of research, describes the nature of that issue, and explains why the issue warrants investigation. Think of it as the framing sentence (or short paragraph) that translates a broad interest into a concrete research problem ready for systematic study.

A useful way to picture it is as a bridge between an observed situation and an intended contribution. For example, a broad observation — “many teachers report burnout” — becomes useful research only when narrowed into a concise statement that specifies who is affected, in what context, and what is not yet understood (for instance: “Despite rising reports of burnout among early-career secondary school teachers in urban districts, there is limited evidence about how mentorship programs influence their retention”). That focused statement of the problem tells readers what’s wrong, where the gap lies, and hints at what kind of evidence the study will provide.

Key characteristics of a good statement of the problem:

- It is focused on a single central issue rather than several unrelated problems.

- It identifies a real gap in existing knowledge or practice.

- It explains the context and the practical or theoretical consequences of leaving the gap unaddressed.

- It explains the context and the practical or theoretical consequences of leaving the gap unaddressed.

- It sets up the scope for the subsequent research question(s) and objectives.

Why is a Problem Statement Important in Research?

A clearly articulated statement of the problem serves several vital roles in the life of a study:

- Guides Scope and Focus: By defining what will (and will not) be studied, it prevents the project from drifting into unrelated areas. This helps you avoid the common pitfall of a project that is “too broad” to be actionable.

- Justifies the Study’s Relevance: A strong statement demonstrates the significance of the research by showing the real-world or theoretical consequences of the issue. It answers the implicit question reviewers and stakeholders always ask: “Why does this matter?”

- Shapes Research Questions and Objectives: Once the problem is clearly stated, specific research questions and research objectives naturally follow. The statement acts like a north star for the rest of the study—methods, sampling, and analysis should all align with it.

- Informs Methodological Choices: Knowing whether the core issue is exploratory (understanding a phenomenon), explanatory (testing relationships), or evaluative (assessing an intervention) helps determine whether qualitative, quantitative, or mixed research methods are appropriate.

- Anchors the Literature Review and Design: The literature review becomes targeted: it searches for what is known about the stated problem, the gaps, and the conceptual frameworks that might help. Likewise, the research design—how you will collect and analyze data—derives from the nature of the problem.

For example, a statement that emphasizes a lack of longitudinal evidence about student engagement will lead to different methods (e.g., cohort design, repeated measures) than a statement emphasizing unexplored experiences (which would suggest qualitative interviews).

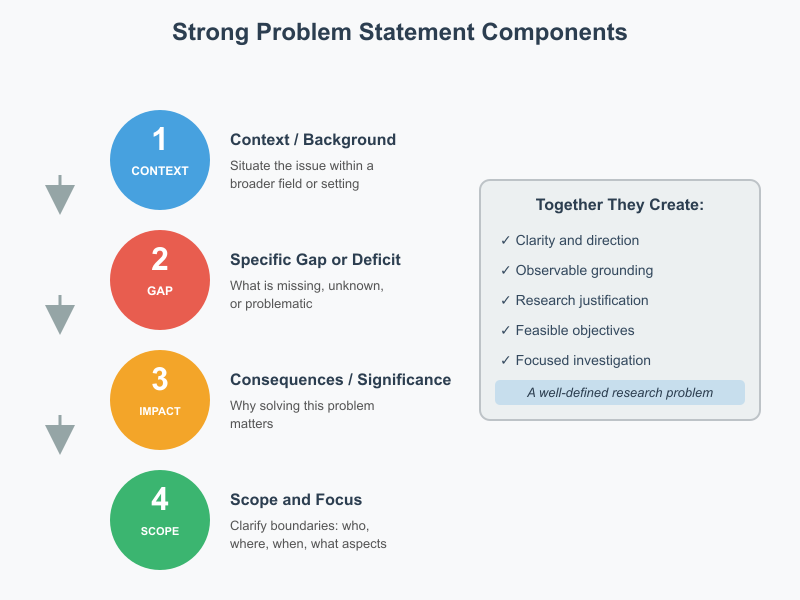

What Are the Key Components of a Strong Problem Statement?

A strong statement of the problem commonly contains four interrelated components. Each component helps to create clarity and direction:

- Context / Background: Briefly situate the issue within a broader field or setting. This orients readers and shows that the problem is grounded in observable facts or literature.

- Specific Gap or Deficit: State exactly what is missing, unknown, ineffective, or problematic in current knowledge or practice. This is the heart of the statement: the identifiable gap that the research project will address.

- Consequences or Significance: Explain what happens if the gap remains unaddressed—practical consequences, policy implications, or theoretical limits. This element communicates why solving the problem matters.

- Scope and Focus: Clarify the boundaries of the study (who, where, when, and which aspects are considered). This prevents overreach and helps shape feasible objectives.

A concise template that many researchers use (and adapt) is:

“In [context], [specific problem] exists, resulting in [negative consequences]. However, [what is not known or has not been done]. This study seeks to [purpose / aim].”

Example:

“In urban community clinics, patient follow-up rates after discharge are low, leading to increased readmission rates and poorer long-term outcomes. Little is known about how a structured telephone follow-up protocol affects 30-day readmission rates among elderly patients. This study aims to evaluate whether implementing a standardized telephone follow-up reduces readmissions and improves care continuity.”

Note how this example provides context, defines the gap, notes consequences, and states an aim tied to the gap.

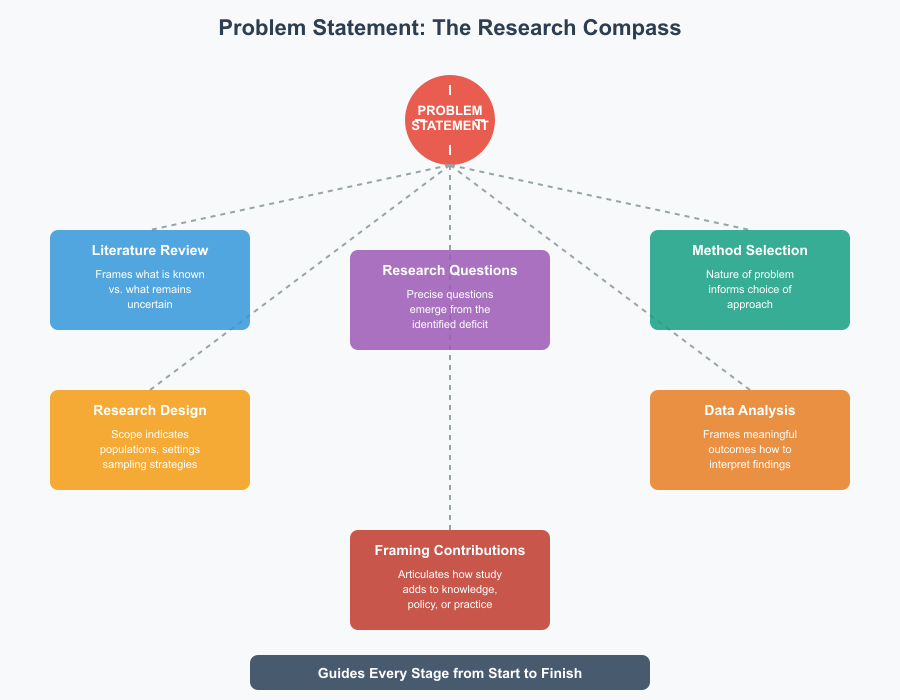

How Does a Problem Statement Guide the Research Process?

The problem statement is the operational compass for the entire research process. Its influence appears at each stage:

- Literature Review: The review is framed around what is known about the stated problem and what remains uncertain—targeted searches rather than general reading.

- Formulation of Research Questions: Precise questions emerge from the deficit identified. For example, a gap about intervention effectiveness becomes a comparative or evaluative question; an unclear phenomenon becomes an exploratory question.

- Selection of Methods: The nature of the problem (e.g., causal vs. descriptive) directly informs whether you choose experiments, surveys, qualitative interviews, or mixed approaches.

- Research Design and Sampling: The scope in the statement indicates which populations, settings, and time frames are relevant and therefore which sampling strategies are appropriate.

- Data Analysis and Interpretation: The statement frames what outcomes or themes are most meaningful to analyze and how findings should be interpreted relative to the initial gap and significance.

- Framing Contributions: Finally, the statement helps you articulate the study’s contribution—how it adds to knowledge, policy, or practice—which is essential for writing conclusions and proposals.

Put simply, when the statement is clear and targeted, every subsequent decision becomes easier and more defensible. When it is vague, researchers risk mismatched methods, unfocused analysis, and unclear conclusions.

How to Identify a Research Problem?

Identifying a viable research problem begins with curiosity plus critical reading. Start by scanning recent literature, conference proceedings, policy reports, and practitioner notes in your field to notice recurring gaps, contradictions, or unanswered questions. Pay attention to statements like “little is known about…”, “the effect of X on Y is unclear”, or “previous studies are limited by…”. Those phrases often signal a fertile area for inquiry.

Next, translate a general interest into a focused issue by asking where the unmet need lies (practice, policy, or theory), who is affected, and what the consequences are. For example, if you are interested in online learning, the observation “students report low engagement” becomes a research problem when you specify population, context, and measure: “Undergraduate engineering students in blended courses show lower engagement on group projects, leading to lower pass rates.” That articulation points toward precise research questions and achievable objectives.

As you move from observation to definition, test the potential problem against practical criteria: is it researchable (can it be investigated with available methods and data?), significant (does it matter to stakeholders or theory?), and original (does it add something beyond existing studies?). If the answer to all three is yes, you likely have a strong basis for a research proposal or project.

What Are the Common Sources of Research Problems?

Research problems commonly emerge from several predictable sources:

- Gaps in the Literature: After a targeted literature review, you may find topics that have been little studied, studied only in narrow contexts, or studied with conflicting results. These gaps are classic places to build a research paper or study.

- Practical Needs and Professional Practice: Problems observed in workplaces, schools, clinics, or communities often generate practical research that aims to solve a real issue. For instance, a hospital noticing frequent medication errors might prompt an evaluative study.

- Theoretical Limitations: When existing theories fail to explain new phenomena or empirical findings, researchers can formulate problems that test or extend those theoretical boundaries.

- Policy Changes and Social Trends: New laws, technologies, or societal shifts can create novel problems requiring timely research.

- Replication and Verification Needs: Sometimes earlier findings need verification in new contexts, populations, or with improved methods—this is especially common when earlier studies used small samples or weak designs.

- Methodological Shortcomings: If prior work used methods that limit inference (e.g., cross-sectional surveys for causal claims), a study using stronger research methods can address the shortcoming.

Each of these sources points to different kinds of studies—exploratory, explanatory, evaluative—and helps you determine appropriate methods and scope.

How Can You Narrow Down a Broad Topic into a Specific Problem?

Narrowing a broad topic requires iteration and boundary-setting:

- Specify Population and Setting: Define who and where. Instead of “teacher burnout,” try “early-career secondary teachers in urban public schools.”

- Define the Outcome or Phenomenon: Be explicit about what aspect you will examine—retention, performance, mental health indicators, etc.

- Limit the Time Frame or Conditions: Consider focusing on a particular period (e.g., first two years of teaching) or condition (schools implementing a new curriculum).

- Identify the Gap in Knowledge or Practice: Ask what is not known or what intervention has not been tried. This becomes the core of your specific problem.

- Draft and Refine Short Statements: Write several one- or two-sentence formulations and test them against feasibility and significance. A concise version should help you derive research questions and research objectives.

Example progression:

Broad topic: “Digital learning in higher education.”

Narrowed topic: “Use of discussion forums in blended nursing courses.”

Specific problem: “Low forum participation in blended nursing courses correlates with poorer clinical reasoning scores; the causal dynamics remain unexplored.”

This specific problem can now be translated into research questions and a feasible design.

What Questions Should You Ask to Define Your Research Problem?

When defining your research problem, ask these probing questions:

- What exactly is happening, and who is affected? (clarifies population and phenomenon)

- Where and when does it occur? (defines context and scope)

- Why does it matter? (identifies significance and potential consequences)

- What do we already know, and what is missing from existing studies? (links to a focused literature review)

- Is the problem measurable or observable with available methods? (assesses feasibility)

- What would solving or better understanding this problem enable? (frames the study’s contribution)

- What are realistic research objectives and possible research questions derived from this problem? (connects problem to design and aims)

Answering these questions helps you move from a general interest to a concise and actionable problem that supports clear research questions and an appropriate research design.

How to Write a Strong Problem Statement?

Writing a strong problem statement begins by translating a real-world issue or theoretical gap into a focused research aim that others can understand and act on. The goal is to make the problem intelligible, relevant, and researchable.

Steps to follow:

- Begin with context. Open with a short description of the setting or population affected. Context anchors the reader and shows that the issue is grounded in observable reality.

- Specify the gap. Clearly indicate what is unknown, inconsistent, or ineffective in existing work. This is the piece your study will address.

- State the consequences. Explain why the gap matters. Who is affected and what negative outcomes follow if the issue is not addressed?

- Link to purpose. End with a sentence that ties the gap to the aim of your study—what you propose to examine, test, or evaluate.

Example (applied):

Context: Many community health clinics lack standardized follow-up after hospital discharge.

Gap: There is limited evidence on whether brief telephone follow-up reduces 30-day readmission among elderly patients.

Consequence: Higher readmission increases costs and worsens patient outcomes.

Purpose sentence: This study will evaluate whether implementing a standardized telephone follow-up protocol reduces 30-day readmissions among discharged patients aged 65 and older.

Practical tips:

- Draft several versions and tighten each iteration to remove unnecessary words.

- Ensure the final version can lead directly to specific research objectives and a testable plan.

- Avoid wording that presumes an outcome (don’t claim effectiveness before you study it).

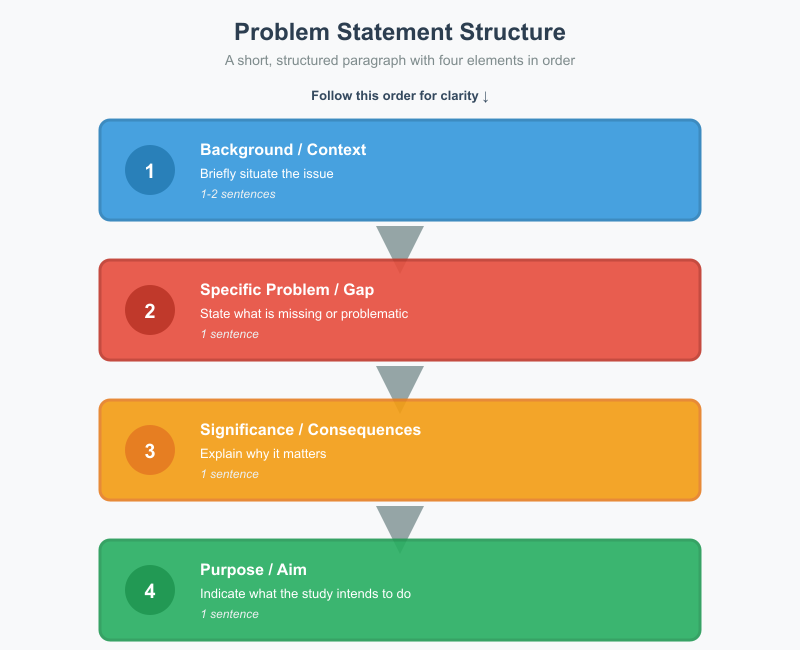

What Structure Should a Problem Statement Follow?

A clear structure helps readers quickly grasp the issue and its importance. Use a short, structured paragraph that contains these elements in order:

- Background / Context (1–2 sentences): Briefly situate the issue.

- Specific Problem / Gap (1 sentence): State what is missing or problematic.

- Significance / Consequences (1 sentence): Explain why it matters.

- Purpose / Aim (1 sentence): Indicate what the study intends to do about it.

Template you can reuse:

“In [context], [specific problem] exists, leading to [negative consequence]. However, [what is unknown]. This study aims to [purpose/aim].”

Example (education):

“In urban secondary schools, novice teachers report high attrition in their first three years, contributing to staffing instability. There is limited evidence on whether structured mentorship programs improve retention in these settings. This study aims to assess the effect of a year-long mentorship program on the retention rates of early-career teachers.”

Why this works:

- It’s concise but complete.

- Each sentence has a discrete role; reviewers can quickly see context, gap, significance, and aim.

- It naturally produces research questions and objectives.

What Language and Tone Should You Use in Your Problem Statement?

Tone and language should be precise, objective, and professional. Your writing should convey seriousness without being overly technical or verbose.

Guidelines:

- Use neutral, evidence-based language. Avoid emotive or persuasive phrases; focus on facts and gaps.

- Prefer active voice and plain language. “X lacks evidence” is clearer than “there are concerns that X…”

- Avoid jargon when possible. If technical terms are necessary, define them briefly.

- Be careful with claims. Don’t make causal claims unless supported by prior research; state what is unknown instead.

- Be concise. Every word should serve a purpose in framing the issue.

Example contrast:

Weak tone: “This terrible problem is causing chaos in clinics and must be fixed.”

Better tone: “In several clinics, inconsistent discharge follow-up is associated with higher readmission; the impact of a standardized follow-up protocol has not been established.”

How Can You Ensure Your Problem Statement is Clear and Concise?

Clarity and concision are achieved through deliberate editing and testing your statement against simple criteria.

Practical steps:

- One-paragraph rule. Keep the statement to a single short paragraph (3–5 sentences). This forces you to prioritize information.

- Read aloud. If it sounds convoluted when spoken, simplify it.

- Check for specificity. Ensure the population, context, and aspect of the problem are explicit. Replace vague terms (e.g., “many,” “some”) with concrete descriptors when possible.

- Link to measurable outcomes. If your problem implies evaluating outcomes (e.g., retention, readmission, engagement), name them; this clarifies the study’s direction.

- Remove assumptions and solutions. State the gap; don’t propose the solution as part of the problem statement (save intervention claims for objectives or hypotheses).

- Peer test. Ask a colleague to read the statement and summarize the problem and aim in one sentence; discrepancies reveal unclear wording.

Example refined progression:

- Draft: “Students have low performance in online classes, which is bad.”

- Revised: “Undergraduate nursing students in blended courses show lower participation in online discussion forums, which correlates with lower clinical reasoning scores; the causes of this correlation are not well understood.”

This revised sentence is specific, measurable, and points to what the research will investigate.

What are Some Examples of Strong Problem Statements?

Strong, usable examples share the same essentials: they set context, name a clear gap, explain why the gap matters, and point toward what the study will do. Below are three worked examples (each shown as a weak version, an improved revision, and a final concise version you could use directly in a proposal or paper).

Example 1 — Education (teacher retention)

- Weak: “Many teachers leave schools early.”

- Improved: “High turnover among early-career secondary teachers in urban public schools contributes to staffing instability and undermines student achievement, but evidence about which retention strategies work in these contexts is limited.”

- Final (concise): “Early-career secondary teachers in urban public schools experience high attrition rates, yet little is known about the effect of structured mentorship programs on their retention; this study will evaluate whether a year-long mentorship reduces attrition in these settings.”

Example 2 — Health (post-discharge follow-up)

- Weak: “Readmissions are a problem.”

- Improved: “Hospital readmission rates within 30 days are elevated among patients discharged from community clinics; inconsistent post-discharge follow-up is suspected but not well documented.”

- Final (concise): “Among older adults discharged from community clinics, inconsistent post-discharge follow-up is associated with higher 30-day readmission; this study examines whether a standardized telephone follow-up protocol reduces readmissions.”

Example 3 — Technology & Learning (online engagement)

- Weak: “Students don’t participate online.”

- Improved: “Undergraduate students in blended courses show low participation in online discussions, which may be linked to lower performance in applied assessments; the drivers of engagement in these cohorts are underexplored.”

- Final (concise): “Undergraduate students in blended courses demonstrate low forum participation that correlates with poorer applied assessment scores; this study will investigate which course design elements predict meaningful online engagement.”

Each final example is short, specific, and directly translatable into objectives and a study plan.

How Can Real-World Examples Help You Craft Your Own Problem Statement?

Real-world examples perform several practical roles when you are developing your own statement:

- Model clarity and economy of language. Seeing how complex issues are reduced to a few precise sentences teaches you to trim extraneous context and focus on measurable elements (population, context, outcome).

- Show how to frame the gap. Examples reveal how to contrast what is known with what is unknown — the core of any research framing — making it easier to justify the study’s relevance.

- Reveal common templates. After reading a few examples, you’ll recognize reusable sentence structures (context → gap → consequence → aim) that speed writing without sacrificing quality.

- Illustrate linkage to design. Practical examples show how a well-phrased description suggests particular designs or measures (e.g., longitudinal data for trends, interviews for lived experience, or randomized designs for intervention effectiveness).

- Help anticipate reviewer expectations. Real cases demonstrate the level of specificity and rigor typical readers expect, which improves acceptability in proposals and journals.

What Makes These Examples Effective?

Effective examples share concrete features you can emulate:

- Specific population and setting. Instead of vague groups like “students” or “patients,” the sample lines name who and where (e.g., “early-career secondary teachers in urban public schools”).

- Clear, measurable outcome. They indicate the outcome or issue that will be observed or measured (e.g., attrition rates, 30-day readmission, forum participation).

- Explicit gap in knowledge or practice. They say what is unknown or insufficiently studied rather than just stating the problem exists.

- Concise consequence statement. They explain why the gap matters (costs, safety, learning outcomes), giving the study practical or theoretical weight.

- Direct link to purpose. Each statement finishes by signalling the study’s aim, which makes downstream tasks (questions, design, analysis) straightforward.

These elements make the statement defendable and actionable—two qualities reviewers and supervisors value.

How Can You Adapt These Samples to Your Research Topic?

Adapting samples is a simple, repeatable process:

- Swap in your population and context. Replace the example’s population/setting with your own (e.g., “community health clinics” → “rural primary care centers”).

- Specify the measurable outcome you care about. Translate general outcomes to the indicators you can collect (e.g., “engagement” → “weekly forum posts or quiz completion rates”).

- Explicitly name the knowledge gap. Use phrases like “limited evidence about…”, “underexplored in…”, or “no studies have examined…” to position your contribution.

- State the consequence and aim. Briefly say why the gap matters locally or theoretically and finish with a short purpose sentence (e.g., “this study will examine…”, “this research evaluates…”).

- Test for feasibility and alignment. Check whether the final phrasing maps clearly to possible methods, data sources, and ethical constraints.

Quick adaptation example:

Sample final (education): “Early-career secondary teachers in urban public schools experience high attrition rates…”

Adapt for another context: “Early-career nurses in regional hospitals experience high turnover during their first two years; little is known about how structured peer mentoring influences retention among nurses in rural settings. This study will evaluate whether a peer mentoring program reduces turnover in regional hospitals.”

The adaptation keeps structure while changing context, outcome, and target population.

What Common Mistakes Should You Avoid When Writing a Problem Statement?

Even experienced researchers can make avoidable errors when framing the issue their study will tackle. Common mistakes to watch for include:

- Being too broad. A description that tries to address an entire field or multiple unrelated concerns will make it hard to write focused research questions or choose appropriate methods.

- Being too narrow or trivial. Conversely, an overly tiny scope (one classroom, one day, one teacher) may produce findings with little general value unless that narrowness is explicitly justified.

- Confusing symptoms with causes. Describing surface symptoms (e.g., “low test scores”) without identifying underlying processes or gaps in knowledge leads to weak study designs.

- Presuming outcomes. Stating that an intervention works before testing it undermines neutrality; the research statement should point to unknowns, not assert solutions.

- Using vague language. Phrases like “many,” “some,” or “a lot” offer no measurable anchor; use specific descriptors and metrics where possible.

- Overloading the statement with methods or solutions. The issue framing should justify inquiry, not prescribe an elaborate method or claim a definitive fix. Methods belong in the design section of a research paper or research proposal.

- Ignoring feasibility. Proposing investigations that require inaccessible data, impossible sampling, or unethical approaches will derail the project at the review stage.

Example of a common error and fix:

Error: “Students perform poorly online, so new teaching tools must be implemented and will work.”

Fix: “Undergraduate students in blended courses show low engagement on discussion forums; the relationship between forum design and applied assessment performance is not established. This study will examine which forum design elements predict deeper engagement.”

What Are the Pitfalls of Being Too Vague or Too Specific?

Both extremes undermine a study’s usefulness—here’s why:

- Too vague: A fuzzy articulation makes it difficult to derive clear research questions, select measures, or justify the study’s significance. Reviewers may ask “What exactly will you study?” and “How will you measure it?” A vague framing also complicates the literature review because it’s unclear which prior studies are relevant.

- Too specific: An excessively narrow focus can limit generalizability and make it hard to recruit adequate samples. It can also signal to reviewers that the problem has limited relevance beyond a single setting or time. However, specificity is valuable when a clear rationale exists (e.g., pilot studies, very new phenomena).

Balancing act example:

- Vague: “Investigate creativity in classrooms.” (Too broad.)

- Overly specific: “Evaluate one teacher’s use of one lesson plan in School X on July 12.” (Too narrow.)

- Balanced: “Explore how collaborative project-based learning influences measured creativity scores among middle-school students across three urban schools during a semester.” (Specific population, outcome, and scope—actionable and generalizable.)

How Can Overcomplicating Your Problem Statement Hinder Your Research?

Complex, multi-part statements often create downstream problems:

- Unclear alignment: If the framing mixes multiple issues (e.g., equity, engagement, and technology adoption), the research questions and design may drift, producing scattered results that don’t answer any of the issues decisively.

- Methodological mismatch: A complicated statement may imply the need for multiple, resource-intensive methods (longitudinal, experimental, ethnographic) that are impractical within one study. This mismatch can lead to weak execution or ethical problems.

- Difficulty writing objectives and hypotheses: When a statement contains numerous subproblems, converting it into concise objectives is laborious and reviewers may challenge the study’s feasibility.

- Reader fatigue: Long, jargon-filled framing reduces clarity and lowers the chance that busy reviewers or stakeholders will grasp the contribution.

Simple remedy: Break complex issues into a primary research statement and clearly labeled secondary questions or sub-studies. If the larger topic demands multiple approaches, consider staging the work (e.g., exploratory study followed by an intervention trial).

What Should You Avoid Including in a Problem Statement?

To keep the focus sharp and defensible, avoid these elements:

- Lengthy literature summaries. A line or two of context is fine, but save the extended review for the literature review section.

- Detailed methodology. Do not specify exact tools, data-collection procedures, or statistical models in the framing sentence(s).

- Value judgments or advocacy language. Phrases like “this unacceptable situation” or “we must fix” sound persuasive rather than scholarly; state the impact objectively.

- Multiple competing problems. Don’t attempt to solve several unrelated problems in a single statement—pick one clear gap.

- Overly technical jargon without explanation. Use clear descriptors; define necessary terms briefly if they are central to the statement.

- Broad claims of generalizability. Avoid saying the study will “revolutionize” a field; frame the expected contribution modestly and specifically.

Illustration of what to avoid:

Poor: “Because the healthcare system is failing, this urgent study will comprehensively overhaul discharge practices using cutting-edge analytics.”

Better: “In several community hospitals, inconsistent discharge follow-up is associated with higher readmission; the effect of a standardized follow-up protocol on 30-day readmissions remains unclear. This study will evaluate the protocol’s impact among patients aged 65 and older.”

How Can You Revise and Improve Your Problem Statement?

Revising is where a good idea becomes a usable research anchor. Treat revision as a multi-stage process that moves from big structural issues to sentence-level polishing.

1. Start with a reverse outline (big picture).

Create a one-line summary for each sentence in your draft statement and check whether those lines form a coherent logical sequence: context → gap → consequence → purpose. If anything off-topic appears, cut or move it. Reverse outlining helps you ensure the statement aligns with the rest of your proposal. (See university revision checklists for this technique.) rwc.byu.edu+1

2. Check alignment with the literature and the gap.

Revisit a targeted search: do the claims you make about “what is unknown” hold up? Tighten wording to reflect exactly what prior studies did or did not show. Replace vague claims (“little is known”) with more precise phrasing when you can (e.g., “no longitudinal studies examine…”).

3. Test for scope and feasibility.

Ask whether the problem as written can be addressed with realistic methods, data, time, and resources. If not, narrow the population, timeframe, or outcome so the study becomes achievable.

4. Convert the statement into concrete questions and objectives.

A well-phrased research aim should yield specific questions and measurable objectives. If you struggle to write clear objectives from the draft, the statement is still too vague or too broad.

5. Move from passive to active, cut filler, and remove solutions.

Tighten language: prefer active verbs, eliminate empty adjectives, and avoid inserting a full proposed solution into the framing (save detailed interventions for the methods). Aim for one paragraph of 3–5 sentences.

6. Do a sentence-level polish.

Read aloud, shorten long clauses, remove jargon or define it, and ensure the final sentence explicitly states the study’s purpose (without presuming outcomes).

Example — revision sequence (short):

- Draft: “There are problems with clinician communication in hospitals and this causes errors.”

- Revised: “In regional hospitals, inconsistent shift-handover communication is linked to medication errors; little evidence exists on whether standardized handover checklists reduce error rates. This study will assess the effect of a standardized checklist on medication error frequency within six months post-implementation.”

What Steps Can You Take to Gather Feedback on Your Problem Statement?

Feedback is essential — aim for a variety of perspectives and structured input.

1. Peers and lab/department colleagues.

Ask peers to read the statement and then (a) summarize the problem in one sentence, and (b) list the single most confusing phrase. If summaries diverge, revise for clarity.

2. Supervisor / mentor review.

Advisors can check for alignment with disciplinary expectations and feasibility. Provide them a short rubric (context, gap, significance, purpose) to speed their feedback.

3. Writing center or institutional reviewers.

Many university writing centers offer experienced editors who help with clarity and structure rather than content. They can perform reverse outlines and give a checklist-style review.

4. Structured peer-review forms.

Use a simple form where reviewers rate the statement on clarity, specificity, significance, and feasibility (1–5) and add one suggestion. Structured forms produce actionable, comparable feedback.

5. Practice presentations.

Present the statement as a 2-minute “elevator pitch” at a lab meeting or seminar and note audience questions — recurring questions indicate unclear portions.

6. Online communities (careful with confidentiality).

For non-sensitive topics, academic forums or discipline-specific Slack/Discord groups can provide quick reactions and references.

How Can Peer Review Enhance the Quality of Your Statement?

Peer review—formal or informal—adds rigor in several ways:

- Checks logic and assumptions. Reviewers often spot implicit assumptions (causal language, scope issues) that you miss. Peer critique helps you rephrase claims to match evidence. PMC+1

- Identifies missing literature or alternative framings. Experts can point you to contradictory work or theoretical lenses you overlooked.

- Improves methodological fit. Peers experienced in methods can advise whether your stated issue is best answered qualitatively, quantitatively, or with a mixed approach.

- Enhances credibility and readability. Multiple rounds of peer input typically produce a tighter, more defensible statement and reduce reviewer pushback later.

Tip: treat peer review as iterative. Collect feedback, revise, then circulate the updated version to the same reviewers to confirm improvements.

Conclusion

Every research journey begins with identifying and articulating a problem statement that captures the essence of what needs to be explored, addressed, or solved. A well-defined research problem serves as the foundation for the entire research project, guiding the formulation of questions, objectives, and methodology. When thoughtfully developed, it transforms vague curiosity into a clear and actionable direction, ensuring that the statement of the problem aligns with both academic and practical relevance.

A strong problem statement does more than simply describe a gap in knowledge—it explains why the problem matters, who it affects, and how the findings might contribute to meaningful change. By defining the specific problem within a broader research area, scholars create a framework for rigorous inquiry and establish the significance of their study. This clarity helps readers, reviewers, and stakeholders understand the purpose of the research and its potential impact.

The process of learning to write a problem statement sharpens analytical thinking, enhances the quality of the research design, and fosters a deeper understanding of the issue at hand. When the problem is clearly defined, researchers can select appropriate research methods, establish measurable research objectives, and conduct an effective literature review to justify their study’s relevance. Moreover, a clear and concise problem statement helps prevent scope creep, ensuring that the entire research project remains focused and coherent from start to finish.

Ultimately, the ability to craft a problem statement is one of the most critical skills in academic research. It connects theoretical knowledge with real-world challenges, enabling researchers to address issues that truly matter within their fields. A well-crafted problem statement not only strengthens the quality of the study but also contributes to the advancement of knowledge and the development of evidence-based solutions. By mastering this foundational step, researchers set the stage for impactful, credible, and purposeful inquiry—laying the groundwork for discoveries that inform policy, improve practice, and address the problem in meaningful ways.

Frequently Asked Questions

How to Write a Good Research Problem Statement with Examples

To write a good research problem statement, start by clearly identifying the issue you want to address, explain why it matters, and describe the gap in existing research. A strong statement should be concise, specific, and logically structured. For example:

- “Despite increased use of telehealth in rural communities, patient adherence to follow-up appointments remains low, indicating a need to explore barriers to consistent virtual care.”

This example defines the specific problem, shows relevance, and points toward the direction of the research study.

What Are Some Good Problem Statement Examples?

Here are a few examples across disciplines:

- Education: “High school students in low-income areas consistently score below the national average in mathematics, suggesting a gap in access to effective instructional resources.”

- Public Health: “Rates of vaccine hesitancy among young adults have increased in urban areas, creating challenges for achieving community immunity.”

- Business: “Small businesses lack affordable access to digital marketing tools, reducing their competitiveness in online markets.”

Each problem statement example identifies a gap, explains its significance, and implies the purpose of the research project.

What Is a Strong Problem Statement?

A strong problem statement is clear, focused, and researchable. It describes the problem in research using precise language and connects the issue to broader research objectives. It also avoids vague or overly complex wording. For instance, saying “There is limited understanding of how workplace stress affects nurse retention in hospitals” is more effective than simply saying “Nurses are stressed.”

What Are the Three Parts to the Problem Statement?

A well-structured problem statement usually includes three key parts:

- Context or background – Introduces the topic and explains its significance.

- Gap or problem – Describes what is missing or not working in existing research or practice.

- Purpose or aim – States what the study intends to achieve or how it will address the problem.

Together, these elements create a clear and concise framework that defines the research problem and guides the rest of the research process.