Pender’s Health Promotion Model: A Comprehensive Guide to the 9 Core Concepts

Pender’s Health Promotion Model (HPM) is a foundational theory that provides a systematic approach to understanding and implementing health promotion strategies. This model emphasizes the significance of individual perceptions, behavior-specific cognitions and affect, and situational influences in the process of adopting and maintaining healthier behaviors.

Historical Overview of Pender’s Health Promotion Model

Pender’s Health Promotion Model was first introduced in the early 1980s by Nola J. Pender, a prominent nursing theorist. Pender developed this model by building on existing health behavior theories such as social cognitive theory and the health belief model. Recognizing the limitations of these earlier models, Pender sought to create a more comprehensive and dynamic framework for understanding health promotion.

The HPM has undergone several revisions since its inception, with the most recent version published in 2015. These revisions have incorporated new research findings and expanded the model’s applicability across various health promotion contexts.

9 Core Concepts of Pender’s Health Promotion Model

The HPM revolves around nine core concepts, each playing a crucial role in influencing an individual’s health behaviors:

- Individual Characteristics and Experiences: This aspect recognizes that each person is unique and is influenced by their own personal experiences, beliefs, and background. Individual characteristics such as age, gender, education, and self-concept can significantly impact an individual’s health behavior choices. For example, a person’s cultural background may influence their dietary preferences and exercise habits.

- Behavioral-Specific Cognitions and Affect: Pender’s model emphasizes the importance of cognition and emotions in shaping health behaviors. These include perceived benefits and barriers, self-efficacy, activity-related affect, and interpersonal influences. Individuals weigh the perceived benefits against the perceived barriers to engaging in a particular health behavior. For instance, someone might consider the health benefits of regular exercise against the time commitment required.

- Behavior-Specific Knowledge and Beliefs: Knowledge and beliefs about health behaviors play a vital role in determining an individual’s likelihood of adopting and maintaining a specific behavior. Health education and communication efforts are crucial in influencing these knowledge and belief structures. For example, educating individuals about the long-term benefits of a balanced diet can influence their food choices.

- Perceived Self-Efficacy: Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s confidence in their ability to perform a specific behavior. High self-efficacy is associated with increased motivation to adopt and maintain healthy behaviors, while low self-efficacy may hinder behavior change efforts. For example, a person with high self-efficacy in their ability to quit smoking is more likely to succeed in their cessation efforts.

- Perceived Benefits of Action: The perceived benefits of engaging in a health behavior significantly impact an individual’s willingness to adopt and maintain that behavior. Highlighting the positive outcomes of a particular behavior can increase its appeal. For instance, emphasizing the improved energy levels and reduced risk of chronic diseases associated with regular exercise can motivate individuals to be more physically active.

- Perceived Barriers to Action: Perceived barriers represent obstacles or challenges that individuals may encounter when attempting to engage in a specific behavior. Identifying and addressing these barriers can enhance behavior change efforts. Common barriers might include lack of time, financial constraints, or limited access to resources. By helping individuals overcome these barriers, health professionals can increase the likelihood of successful behavior change.

- Activity-Related Affect: This concept encompasses emotions and feelings associated with engaging in a health behavior. Positive emotions linked to the behavior can enhance motivation, while negative affect may hinder progress. For example, if someone enjoys the feeling of relaxation after yoga, they are more likely to continue practicing regularly.

- Interpersonal Influences: Interpersonal relationships and social support systems can significantly impact an individual’s health behaviors. Supportive networks and encouragement from family, friends, or healthcare providers can foster positive behavioral changes. For instance, having a workout buddy or joining a support group can increase adherence to an exercise regimen or smoking cessation program.

- Situational Influences: Situational factors, such as the physical and social environment, can either facilitate or hinder behavior change. Understanding and modifying these factors can improve the likelihood of successful behavior adoption and maintenance. Examples include workplace wellness programs, community health initiatives, or the availability of healthy food options in a neighborhood.

Assumptions of Pender’s Health Promotion Model

Pender’s Health Promotion Model is based on several key assumptions that underpin its approach to health promotion:

- Individuals seek to actively regulate their own behavior: The model assumes that people are not passive recipients of health information but actively engage in shaping their health behaviors.

- Individuals interact with their environment, progressively transforming the environment and being transformed over time: This assumption recognizes the dynamic interplay between individuals and their surroundings.

- Health professionals constitute a part of the interpersonal environment: Healthcare providers are seen as influential factors in shaping an individual’s health behaviors.

- Self-initiated reconfiguration of person-environment interactive patterns is essential to behavior change: The model emphasizes the importance of personal agency in modifying health behaviors.

- Individuals have the capacity for reflective self-awareness: This includes the ability to assess one’s own competencies and health-related desires.

- Individuals value growth in directions viewed as positive and attempt to achieve a personally acceptable balance between change and stability: The model recognizes that people strive for personal growth while maintaining a sense of equilibrium.

- Individuals seek to actively regulate their behavior: This assumption highlights the proactive nature of health behavior adoption and maintenance.

- Prior behavior and inherited and acquired characteristics influence beliefs, affect, and enactment of health-promoting behavior: The model acknowledges the impact of past experiences and personal traits on current health behaviors.

- Families, peers, and health care providers are important sources of interpersonal influence: This assumption recognizes the significant role of social networks in shaping health behaviors.

- Situational and personal factors influence the likelihood of engaging in health-promoting behavior: The model takes into account both environmental and individual factors that affect health behavior choices.

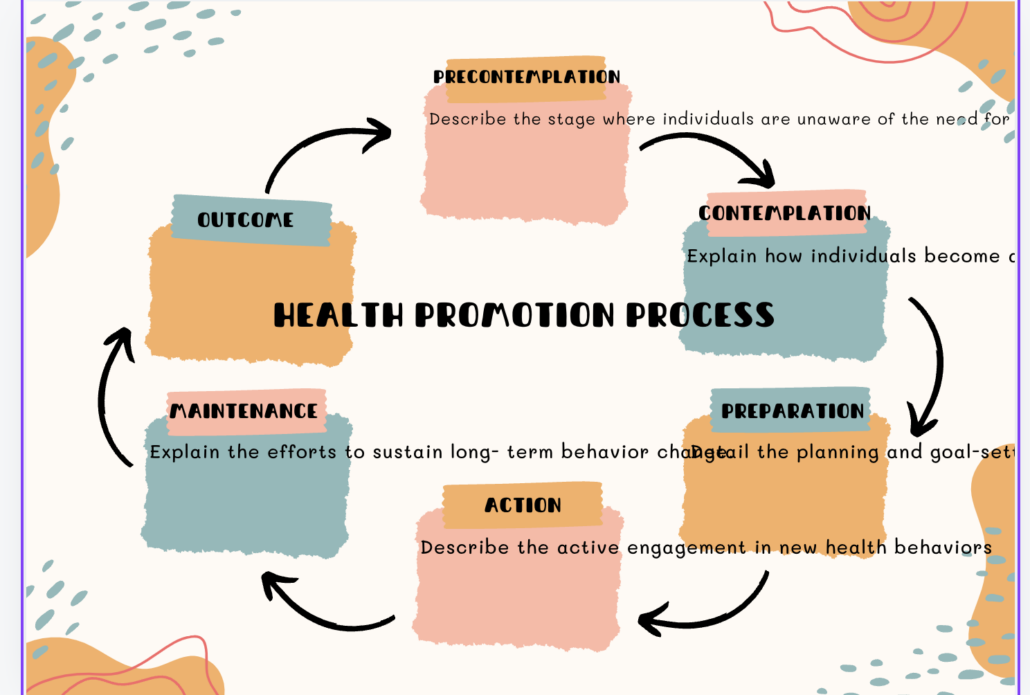

The Health Promotion Process

Pender’s Health Promotion Model outlines a dynamic and cyclical process through which individuals adopt and maintain health-promoting behaviors. This process consists of the following stages:

- Precontemplation: In this stage, individuals may not be aware of the need for behavior change or may lack the motivation to consider change. Health professionals can focus on raising awareness and providing information about potential health risks and benefits.

- Contemplation: During this stage, individuals become aware of the benefits of behavior change and seriously consider adopting healthier behaviors. They may weigh the pros and cons of making a change. Health professionals can provide support and information to help individuals move towards action.

- Preparation: In the preparation stage, individuals plan and set goals for behavior change, seeking resources and support to facilitate their efforts. This may involve making small changes or gathering necessary supplies. Health professionals can assist in developing realistic action plans and identifying potential barriers.

- Action: The action stage involves actively engaging in the new behavior and implementing the planned changes. This is a critical phase where individuals may need the most support and encouragement. Health professionals can provide guidance, positive reinforcement, and help in overcoming obstacles.

- Maintenance: In the maintenance stage, individuals work to sustain the behavior change over time, ensuring it becomes a consistent part of their lifestyle. This stage focuses on preventing relapse and integrating the new behavior into daily routines. Health professionals can help individuals develop strategies for long-term success and provide ongoing support.

Applications of Pender’s Health Promotion Model

The Health Promotion Model has found widespread application in various health-related fields, including:

- Nursing Practice: In nursing, the model helps to guide patient care by assessing individual characteristics, identifying perceived barriers, and designing interventions to promote health and prevent illness. Nurses can use the model to create personalized care plans that address patients’ unique needs and motivations.

- Health Education and Promotion: Health educators use the model to design effective health promotion programs and interventions tailored to the needs and characteristics of their target audience. This may include developing educational materials, conducting workshops, or creating online resources that address specific health behaviors.

- Public Health Interventions: Pender’s model has informed the development of community-based programs aimed at addressing public health issues such as smoking cessation, physical activity promotion, and nutrition education. Public health professionals can use the model to design and implement large-scale interventions that consider both individual and environmental factors.

- Chronic Disease Management: The model provides valuable insights into supporting individuals with chronic conditions in adopting healthier lifestyles and adhering to their treatment plans. Healthcare providers can use the model to develop comprehensive management strategies that address the multifaceted nature of chronic disease care.

- Workplace Wellness Programs: Organizations can apply the HPM to design effective workplace wellness initiatives that promote employee health and well-being. This may include implementing health risk assessments, offering fitness classes, or creating supportive environments for healthy eating.

- School-Based Health Promotion: Educators and school health professionals can use the model to develop age-appropriate health promotion programs for students, addressing issues such as physical activity, nutrition, and mental health.

- Research and Theory Development: The HPM serves as a framework for conducting research on health behaviors and developing new theories in health promotion. Researchers can use the model to design studies that explore the relationships between various factors influencing health behaviors.

Critique and Limitations of Pender’s Health Promotion Model

While Pender’s Health Promotion Model has garnered widespread recognition, it is essential to acknowledge its limitations and potential criticisms:

- Limited Predictive Power: The model may not always accurately predict individual health behavior outcomes, as human behavior is influenced by a complex interplay of factors. Some critics argue that the model’s focus on individual factors may oversimplify the complexity of health behavior change.

- Individual Variability: As with any theoretical framework, individual variability must be considered, as not all individuals will respond uniformly to the same interventions. The model may not fully account for the diverse ways in which people interpret and respond to health-related information and experiences.

- Cultural Relevance: The model’s applicability may vary across different cultural contexts, and cultural considerations must be incorporated into health promotion efforts. Some researchers argue that the model may reflect Western cultural values and may need adaptation for use in diverse global settings.

- Static Nature: Some critics argue that the model does not sufficiently address the dynamic nature of health behaviors over time. Health behaviors may fluctuate due to changing life circumstances, and the model may not fully capture these temporal aspects.

- Limited Focus on Social Determinants: While the model acknowledges situational influences, some argue that it does not place enough emphasis on broader social determinants of health, such as socioeconomic status, education, and access to healthcare.

- Complexity: The comprehensive nature of the model, while a strength, can also be a limitation in practical application. Healthcare providers and researchers may find it challenging to operationalize all components of the model in their work.

Pender’s Health Promotion Model is a powerful tool for understanding health behaviors and designing effective interventions to promote health and wellness. Its emphasis on individual perceptions, behavior-specific cognitions, and situational influences provides a comprehensive understanding of the health promotion process.

By incorporating this model into practice, health professionals and educators can work towards fostering lasting behavioral changes and improving the overall well-being of individuals and communities. The model’s holistic approach encourages a consideration of multiple factors influencing health behaviors, from personal beliefs and experiences to environmental and social influences.

As the healthcare landscape continues to evolve, Pender’s model remains an essential guide for enhancing health promotion efforts and advancing public health initiatives. Its flexibility allows for adaptation to various health contexts and populations, making it a valuable framework for addressing diverse health challenges.

Future research and applications of the Health Promotion Model may focus on integrating emerging technologies, addressing global health disparities, and exploring the model’s relevance in the context of evolving healthcare systems. By continuing to refine and expand upon Pender’s work, health professionals can enhance their ability to support individuals in achieving and maintaining optimal health and well-being.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How does Pender’s Health Promotion Model differ from other health behavior theories?

Pender’s Health Promotion Model (HPM) distinguishes itself from other health behavior theories in several key ways:

- Positive Approach: Unlike models that focus on disease prevention, the HPM emphasizes positive health-promoting behaviors and overall well-being.

- Comprehensive Framework: The HPM integrates multiple factors, including individual characteristics, cognitions, and environmental influences, providing a more holistic view of health behavior.

- Focus on Self-Efficacy: While other models may consider self-efficacy, the HPM places particular emphasis on this concept as a crucial determinant of health behavior.

- Dynamic Process: The model recognizes health promotion as an ongoing, cyclical process rather than a linear progression.

- Integration of Nursing Perspective: Developed by a nurse theorist, the HPM incorporates nursing-specific insights into health promotion strategies.

Compared to models like the Health Belief Model or the Theory of Planned Behavior, the HPM offers a more comprehensive and nuanced approach to understanding and promoting health behaviors across various contexts.

2. How can healthcare providers effectively apply Pender’s Health Promotion Model in clinical practice?

Healthcare providers can apply Pender’s Health Promotion Model in clinical practice through several strategies:

- Comprehensive Assessment: Conduct thorough assessments of patients’ individual characteristics, health beliefs, perceived benefits and barriers, and environmental influences.

- Personalized Goal Setting: Work with patients to set realistic, achievable health goals based on their unique circumstances and motivations.

- Enhance Self-Efficacy: Develop interventions that build patients’ confidence in their ability to perform health-promoting behaviors, such as providing skills training or breaking down complex behaviors into manageable steps.

- Address Barriers: Identify and help patients overcome perceived barriers to health-promoting behaviors, whether they are personal, social, or environmental.

- Leverage Social Support: Encourage involvement of family members or peers in the health promotion process and consider referrals to support groups or community resources.

- Tailor Education: Provide health education that is tailored to the patient’s knowledge level, cultural background, and specific health concerns.

- Create Supportive Environments: Advocate for and help create environments that facilitate healthy behaviors, both within healthcare settings and in the broader community.

- Regular Follow-up: Implement regular follow-up assessments to monitor progress, provide ongoing support, and adjust interventions as needed.

- Utilize Technology: Incorporate technology-based tools, such as health apps or telemedicine, to support ongoing health promotion efforts.

- Interdisciplinary Collaboration: Work with other healthcare professionals to provide comprehensive, coordinated care that addresses all aspects of the HPM.

By integrating these strategies into their practice, healthcare providers can effectively use the HPM to promote positive health behaviors and improve patient outcomes.

3. What are some critiques of Pender’s Health Promotion Model, and how have these been addressed in recent research?

While Pender’s Health Promotion Model has been widely adopted, it has faced several critiques:

- Limited Predictive Power: Some researchers argue that the model’s complexity makes it difficult to predict health behaviors accurately. Recent Developments: Studies have focused on refining measurement tools and statistical methods to improve the model’s predictive capacity. Some researchers have proposed simplified versions of the model for specific contexts.

- Cultural Limitations: Critics suggest the model may not be universally applicable across diverse cultural contexts. Recent Developments: There has been an increase in cross-cultural studies applying the HPM, leading to culturally adapted versions of the model. Researchers have also explored how cultural factors can be better integrated into the model’s framework.

- Insufficient Attention to Social Determinants: Some argue that the model doesn’t adequately address broader social and economic factors influencing health. Recent Developments: Recent studies have attempted to incorporate social determinants of health more explicitly into the HPM framework, expanding its scope to consider factors like socioeconomic status and health literacy.

- Static Nature: Critics argue that the model doesn’t fully capture the dynamic nature of health behaviors over time. Recent Developments: Longitudinal studies applying the HPM have increased, providing insights into how health behaviors change over time. Some researchers have proposed incorporating elements of stage-based models to address this limitation.

- Complexity in Application: The comprehensive nature of the model can make it challenging to apply in practice. Recent Developments: Researchers have developed simplified tools and guidelines for applying the HPM in various healthcare settings. There’s also been a focus on creating digital applications that can help healthcare providers use the model more efficiently.

- Limited Focus on Negative Health Behaviors: Some argue that the model’s emphasis on positive health promotion neglects the importance of addressing harmful behaviors. Recent Developments: Recent studies have explored how the HPM can be applied to understand and intervene in negative health behaviors, expanding its applicability in addiction and risk behavior contexts.

These ongoing developments demonstrate the model’s adaptability and the research community’s commitment to refining