Top Lab Values Every Nursing Student Must Know for USMLE and NBME Exams

NBME and USMLE Lab Values form a critical foundation for understanding physiological status, disease progression, and clinical decision-making. Laboratory data provide objective insights that guide diagnosis, monitoring, and therapeutic interventions, spanning hematology, metabolism, liver function, renal assessment, and endocrine evaluation. Mastery of these lab values and their corresponding reference ranges is essential for interpreting deviations from the normal range and understanding their physiological and pathological implications.

Laboratory results are more than numbers—they reflect complex interactions within the body’s systems. For instance, subtle changes in serum lactate may indicate tissue hypoperfusion, while elevated ferritin, serum iron, and transferrin levels can signify iron overload or deficiency states, guiding further investigation. Similarly, minor fluctuations in electrolyte concentrations, creatinine, or hemoglobin can signal early renal, hematological, or metabolic derangements. Recognizing these variations requires not only knowledge of normal values but also an understanding of how these laboratory findings relate to clinical pathology, laboratory medicine principles, and physiological regulation.

Interpreting laboratory tests effectively depends on familiarity with SI and conventional units, assay types, and the standard unit of measurement for each analyte. Misinterpretation of laboratory parameters due to unit discrepancies or failure to recognize clinically significant deviations can impact diagnosis and monitoring, affecting patient care outcomes. For example, an elevated AST in the context of liver injury must be interpreted alongside ALT, bilirubin, and alkaline phosphatase to distinguish hepatocellular damage from cholestatic patterns.

Laboratory assessments are integral to understanding hematological, metabolic, hepatic, and endocrine systems. Key tests, including RBC indices, platelet counts, coagulation panels, thyroid hormones, cortisol, and growth hormone levels, provide insight into systemic function and disease processes. Monitoring urine composition, serum electrolytes, and metabolic panels further enhances the ability to detect early disturbances, anticipate complications, and implement targeted interventions. Even immunology-based laboratory assays, such as antibody detection, are crucial in evaluating physiological or pathological states.

The integration of NBME and USMLE Lab Values into clinical reasoning strengthens interpretation skills and enhances the diagnostic utility of laboratory data. Systematic evaluation of lab results, understanding the normal ranges, and recognizing patterns of deviation are fundamental to accurate clinical evaluation and progression monitoring. This knowledge supports the application of laboratory medicine principles across diverse areas, including hematology, hepatology, endocrinology, and metabolic assessment, offering a comprehensive framework for analyzing laboratory findings in both exam and clinical contexts.

In essence, mastery of NBME and USMLE Lab Values transcends memorization. It is a structured approach to evaluating laboratory parameters, interpreting deviations, and applying findings to real-world clinical situations. By understanding the nuances of reference values, serum concentrations, and physiological implications, clinicians can enhance diagnostic accuracy, optimize patient care, and navigate complex clinical scenarios with confidence.

Essential Laboratory Reference Ranges for Exam Success

Accurate interpretation of laboratory values is foundational for both clinical decision-making and performance on USMLE and NBME exams. Understanding reference ranges, recognizing the importance of units, and applying a structured approach to abnormal findings is essential for reliable diagnosis, monitoring, and metabolic evaluation. This section provides an in-depth exploration of laboratory reference ranges, the nuances of SI and conventional units, the methodology for converting concentrations, and a systematic framework for evaluating abnormal lab results.

Understanding Laboratory Reference Ranges and Units

Reference ranges are established using data from healthy populations, typically encompassing the central 95% of values. These ranges act as a standard for distinguishing normal physiological variability from pathological deviations. Clinically, comparing a patient’s result to the reference range allows the practitioner to identify whether a value is within expected limits, slightly abnormal, or significantly deranged. For example, a hemoglobin of 11 g/dL in an adult female, against a reference range of 12–15 g/dL, would immediately trigger evaluation for anemia, prompting further investigations such as RBC indices, ferritin levels, and serum iron.

The interpretation of laboratory data is complicated by the use of SI (International System) units and conventional units. SI units, such as mmol/L or g/L, are standardized globally, whereas conventional units like mg/dL are still common in the United States. The ability to convert between these units is critical for accurate interpretation. For example, creatinine reported as 1.0 mg/dL in conventional units equates to approximately 88 μmol/L in SI units. Similarly, hemoglobin reported as 13.4 g/dL translates to 134 g/L. Misinterpretation due to incorrect units can lead to misdiagnosis or unnecessary intervention.

Laboratories provide specific reference ranges alongside each test result because assay methods, instrument calibration, and population differences influence normal values. Clinicians must interpret results relative to the laboratory-provided reference rather than relying solely on textbook standards. For example, sodium concentrations measured in mmol/L may vary slightly between laboratories depending on the assay used, and what is normal in one lab may be flagged as abnormal in another.

Understanding why units matter is equally critical. The unit of measurement provides context to the numerical value, defining the actual concentration of a substance in plasma or serum. For instance, interpreting calcium or bicarbonate levels without accounting for units can dramatically alter clinical judgment. Even electrolytes with numerically similar SI and conventional units require careful attention in clinical and exam settings to avoid misclassification.

Systematic Approach to Interpreting Abnormal Lab Values

A structured approach is essential for evaluating abnormal lab values, particularly in high-stakes examinations and clinical practice. The following step-by-step framework ensures accuracy and enhances diagnostic reasoning:

- Confirm the Units and Reference Ranges:

Always verify whether results are reported in SI or conventional units. Compare values against the laboratory-specific reference ranges to determine normalcy. This step prevents misinterpretation due to unit discrepancies. - Identify Abnormal Values:

Focus on values outside the expected range. Classify them as mild, moderate, or severe deviations based on their magnitude relative to the reference range. For example, a potassium of 5.5 mmol/L represents mild hyperkalemia, whereas 7.0 mmol/L is critically high and demands urgent intervention. - Look for Patterns Across Related Parameters:

Isolated abnormalities provide limited information. By evaluating clusters of laboratory parameters, clinicians can identify systemic patterns. For instance, simultaneous elevation of AST and ALT with normal alkaline phosphatase suggests hepatocellular injury, whereas elevated alkaline phosphatase with normal AST/ALT indicates a cholestatic pattern. - Consider the Metabolic and Clinical Context:

Integrating laboratory results with patient presentation and comorbidities is critical. Elevated lactate in a hypotensive patient may indicate tissue hypoperfusion and sepsis, whereas a mild elevation in an otherwise healthy individual after exercise may be physiologically normal. - Evaluate Trends Over Time:

Sequential laboratory measurements provide insight into disease progression or resolution. Tracking trends in creatinine, electrolytes, or liver function tests helps identify worsening pathology or response to treatment, offering more information than isolated values. - Incorporate Laboratory Medicine Principles:

Factors such as pre-analytical variability (e.g., sample handling), analytical differences (assay methods), and post-analytical interpretation must be considered. Understanding these principles ensures that abnormal lab values are interpreted within the correct methodological and clinical context.

Practical Example

Consider a patient presenting with the following laboratory values:

- Sodium: 132 mmol/L (low)

- Potassium: 5.8 mmol/L (high)

- Creatinine: 1.7 mg/dL (slightly high)

- Glucose: 180 mg/dL (elevated)

Using the systematic approach:

- Verify Units: Confirm mmol/L for electrolytes and mg/dL for glucose and creatinine.

- Compare to Reference Ranges: Sodium (136–146 mmol/L), potassium (3.5–5.0 mmol/L), creatinine (0.6–1.2 mg/dL), glucose (70–100 mg/dL fasting).

- Identify Abnormalities: Hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, mild renal impairment, and hyperglycemia.

- Evaluate Patterns: Electrolyte disturbances with rising creatinine suggest acute kidney injury.

- Consider Clinical Context: Hyperglycemia could indicate stress response, prediabetes, or undiagnosed diabetes.

- Formulate Diagnostic Plan: Urgent management of hyperkalemia, monitoring renal function, and assessment of metabolic status.

This approach mirrors USMLE lab values–type questions, where interpretation of a pattern of laboratory abnormalities is critical for determining the correct diagnosis and intervention.

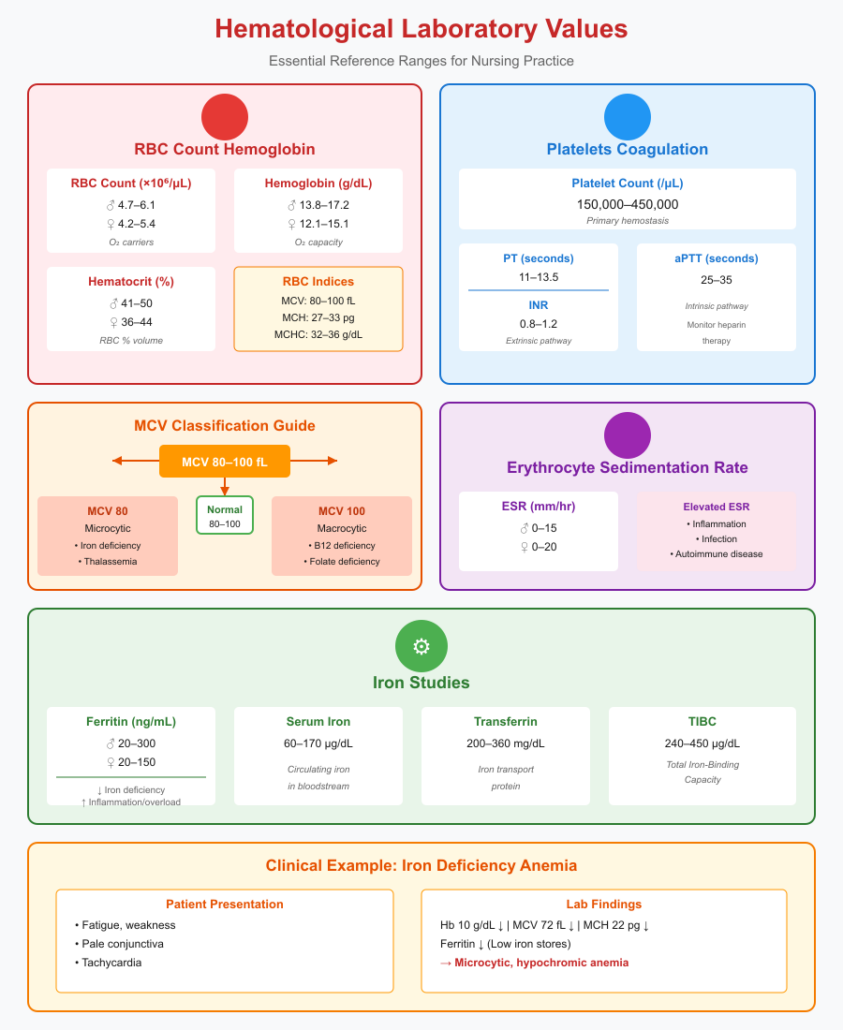

Hematological Laboratory Values Every Nursing Student Should Memorize

Hematological laboratory values provide a window into the functional and structural integrity of blood, reflecting both systemic health and underlying disease processes. Accurate interpretation of RBCs, hemoglobin, RBC indices, platelet counts, coagulation parameters, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and iron studies is crucial for both clinical practice and USMLE/NBME–style exam scenarios. Mastery of these parameters ensures appropriate diagnosis, monitoring, and clinical decision-making.

RBC, Hemoglobin, and RBC Indices

Red blood cells (RBCs) are the primary carriers of oxygen and carbon dioxide. Evaluation includes RBC count, hemoglobin (Hb), hematocrit (Hct), and RBC indices (MCV, MCH, MCHC). These measures allow for assessment of oxygen-carrying capacity, identification of anemias, and differentiation between various hematological disorders.

Normal Ranges and Significance:

- RBC Count:

- Adult males: 4.7–6.1 ×10^6/μL

- Adult females: 4.2–5.4 ×10^6/μL

- Deviations:

- Low RBC count: Anemia, blood loss, bone marrow suppression

- High RBC count: Polycythemia, dehydration, chronic hypoxia

- Hemoglobin (Hb):

- Males: 13.8–17.2 g/dL

- Females: 12.1–15.1 g/dL

- Low Hb often indicates iron deficiency, chronic disease, or hemorrhage. Elevated Hb may reflect dehydration, hypoxia, or polycythemia vera.

- Hematocrit (Hct):

- Males: 41–50%

- Females: 36–44%

- Provides a percentage of blood volume occupied by RBCs, aiding in evaluation of anemia or polycythemia.

- RBC Indices:

- Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV): 80–100 fL

- Low MCV → microcytic anemia (iron deficiency, thalassemia)

- High MCV → macrocytic anemia (B12 or folate deficiency)

- Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin (MCH): 27–33 pg

- Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration (MCHC): 32–36 g/dL

- Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV): 80–100 fL

Clinical Example:

A patient with fatigue has Hb 10 g/dL, MCV 72 fL, MCH 22 pg, and low ferritin. These hematological laboratory values indicate microcytic, hypochromic anemia consistent with iron deficiency, guiding targeted supplementation and follow-up monitoring.

Platelet Count and Coagulation Parameters

Platelets are critical for primary hemostasis, and coagulation parameters assess the integrity of clotting pathways. Accurate interpretation is essential for detecting bleeding disorders, thrombosis, and guiding anticoagulation therapy.

Normal Platelet Range and Coagulation Parameters:

- Platelet Count: 150,000–450,000/μL

- Thrombocytopenia (<150,000/μL) → increased bleeding risk, often due to bone marrow suppression or immune-mediated destruction.

- Thrombocytosis (>450,000/μL) → risk of thrombosis, may be reactive to inflammation or iron deficiency.

- Prothrombin Time (PT): 11–13.5 seconds

- International Normalized Ratio (INR): 0.8–1.2 (therapeutic anticoagulation ranges are higher)

- Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (aPTT): 25–35 seconds

Clinical Significance:

- PT and INR assess the extrinsic pathway, commonly used to monitor warfarin therapy.

- aPTT evaluates the intrinsic pathway, relevant for heparin monitoring.

- Combined evaluation of platelet count and coagulation parameters is crucial in patients with bleeding or clotting disorders.

Example:

A patient with platelet count 90,000/μL and elevated aPTT presents with spontaneous bruising. Interpretation of these laboratory parameters suggests thrombocytopenia and intrinsic pathway coagulation dysfunction, prompting evaluation for conditions such as immune thrombocytopenia or coagulopathy.

Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) and Iron Studies

ESR and iron studies provide insight into systemic inflammation and iron metabolism, aiding in the diagnosis of anemia, chronic inflammatory states, and hematologic disorders.

Reference Ranges and Diagnostic Relevance:

- ESR:

- Men: 0–15 mm/hr

- Women: 0–20 mm/hr

- Elevated ESR indicates inflammation, infection, or autoimmune disease but is nonspecific.

- Ferritin: 20–300 ng/mL (men), 20–150 ng/mL (women)

- Low ferritin → iron deficiency anemia

- High ferritin → inflammatory conditions, iron overload

- Serum Iron: 60–170 μg/dL

- Transferrin: 200–360 mg/dL

- Total Iron-Binding Capacity (TIBC): 240–450 μg/dL

Clinical Example:

A patient with fatigue and pallor has low ferritin (10 ng/mL), low serum iron (45 μg/dL), and elevated transferrin. These laboratory reference values confirm iron deficiency anemia, guiding oral iron therapy and dietary counseling. Simultaneous assessment of ESR helps exclude anemia of chronic disease, where ferritin may be elevated due to inflammation.

Integrative Approach

To accurately interpret hematological laboratory values:

- Always assess RBC, hemoglobin, and RBC indices collectively to classify anemia (microcytic, macrocytic, normocytic).

- Evaluate platelet counts alongside PT, aPTT, and INR for comprehensive coagulation assessment.

- Integrate ESR and iron studies to distinguish between iron deficiency, anemia of chronic disease, and other systemic conditions.

- Consider trends, patient history, and clinical symptoms to contextualize laboratory parameters in real-world scenarios.

This systematic evaluation ensures that abnormal values are not interpreted in isolation, enhancing both diagnostic accuracy and performance in USMLE and NBME exam-style questions.

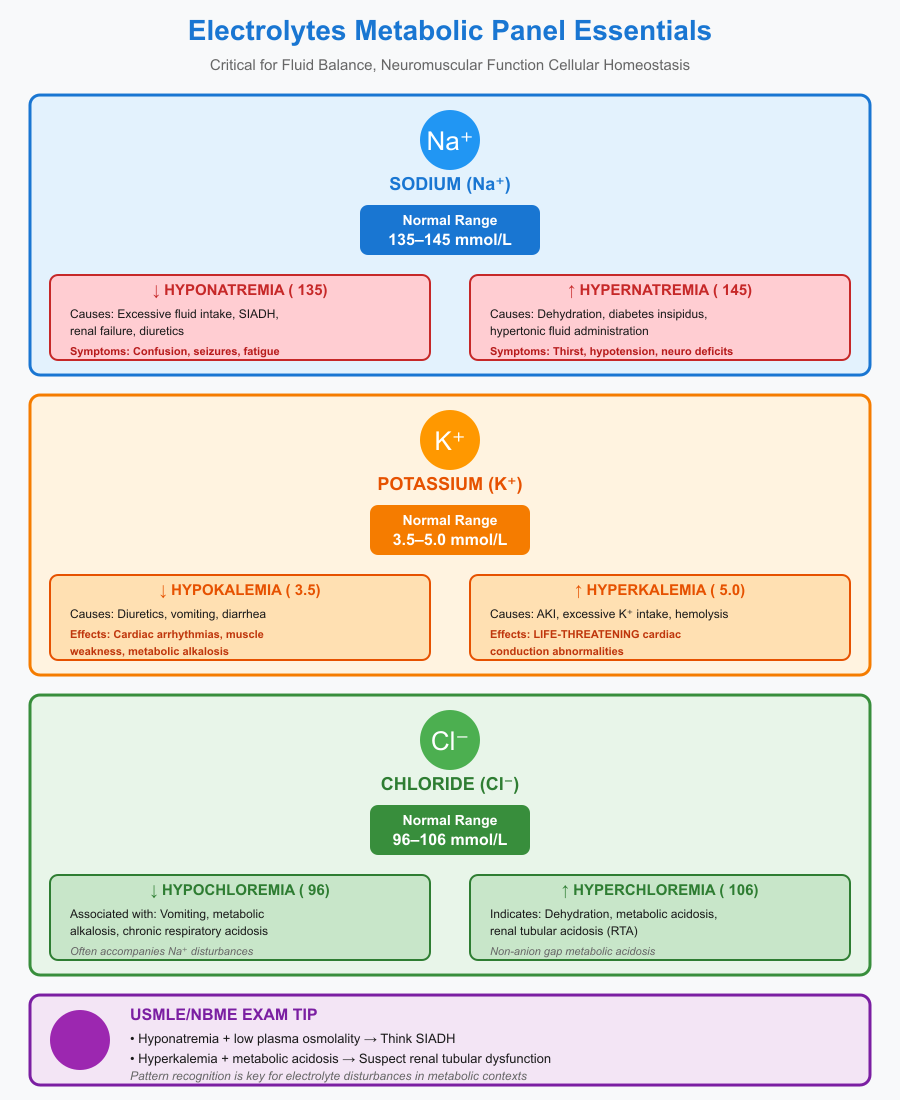

Electrolytes and Metabolic Panel Essentials

A thorough understanding of electrolytes and metabolic panel laboratory values is essential for evaluating a patient’s systemic physiology, detecting metabolic disturbances, and answering high-yield USMLE and NBME exam questions. Electrolytes such as sodium, potassium, and chloride, along with metabolic markers like glucose, lactate, BUN, creatinine, and estimated GFR, provide critical insight into renal, cardiovascular, and endocrine function. Proper interpretation requires knowledge of normal ranges, metabolic relevance, and laboratory parameters, as well as awareness of patterns that indicate pathophysiology.

Serum Sodium, Potassium, and Chloride Ranges

Electrolytes play a vital role in maintaining fluid balance, neuromuscular function, and cellular homeostasis. Deviations from normal reference ranges can indicate dehydration, renal dysfunction, acid-base disorders, or endocrine abnormalities.

Normal Reference Ranges:

- Sodium (Na⁺): 135–145 mmol/L

- Potassium (K⁺): 3.5–5.0 mmol/L

- Chloride (Cl⁻): 96–106 mmol/L

Clinical Relevance:

- Hyponatremia (Na⁺ < 135 mmol/L): May result from excessive fluid intake, SIADH (syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone), renal failure, or diuretic therapy. Symptoms include confusion, seizures, and fatigue.

- Hypernatremia (Na⁺ > 145 mmol/L): Often due to dehydration, diabetes insipidus, or hypertonic fluid administration. Presents with thirst, hypotension, or neurologic deficits.

- Hypokalemia (K⁺ < 3.5 mmol/L): Commonly caused by diuretics, vomiting, or diarrhea. Can lead to cardiac arrhythmias, muscle weakness, and metabolic alkalosis.

- Hyperkalemia (K⁺ > 5.0 mmol/L): Often due to acute kidney injury, excessive potassium intake, or hemolysis. Can precipitate life-threatening cardiac conduction abnormalities.

- Hypochloremia (Cl⁻ < 96 mmol/L): Associated with vomiting, metabolic alkalosis, or chronic respiratory acidosis.

- Hyperchloremia (Cl⁻ > 106 mmol/L): May indicate dehydration, metabolic acidosis, or renal tubular acidosis.

Exam Tip: Many USMLE questions present electrolyte disturbances in the context of metabolic abnormalities. For instance, a patient with hyponatremia and low plasma osmolality may be exhibiting SIADH, while hyperkalemia with metabolic acidosis suggests renal tubular dysfunction.

Electrolytes and Metabolic Panel Essentials

A thorough understanding of electrolytes and metabolic panel laboratory values is essential for evaluating a patient’s systemic physiology, detecting metabolic disturbances, and answering high-yield USMLE and NBME exam questions. Electrolytes such as sodium, potassium, and chloride, along with metabolic markers like glucose, lactate, BUN, creatinine, and estimated GFR, provide critical insight into renal, cardiovascular, and endocrine function. Proper interpretation requires knowledge of normal ranges, metabolic relevance, and laboratory parameters, as well as awareness of patterns that indicate pathophysiology.

Serum Sodium, Potassium, and Chloride Ranges

Electrolytes play a vital role in maintaining fluid balance, neuromuscular function, and cellular homeostasis. Deviations from normal reference ranges can indicate dehydration, renal dysfunction, acid-base disorders, or endocrine abnormalities.

Normal Reference Ranges:

- Sodium (Na⁺): 135–145 mmol/L

- Potassium (K⁺): 3.5–5.0 mmol/L

- Chloride (Cl⁻): 96–106 mmol/L

Clinical Relevance:

- Hyponatremia (Na⁺ < 135 mmol/L): May result from excessive fluid intake, SIADH (syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone), renal failure, or diuretic therapy. Symptoms include confusion, seizures, and fatigue.

- Hypernatremia (Na⁺ > 145 mmol/L): Often due to dehydration, diabetes insipidus, or hypertonic fluid administration. Presents with thirst, hypotension, or neurologic deficits.

- Hypokalemia (K⁺ < 3.5 mmol/L): Commonly caused by diuretics, vomiting, or diarrhea. Can lead to cardiac arrhythmias, muscle weakness, and metabolic alkalosis.

- Hyperkalemia (K⁺ > 5.0 mmol/L): Often due to acute kidney injury, excessive potassium intake, or hemolysis. Can precipitate life-threatening cardiac conduction abnormalities.

- Hypochloremia (Cl⁻ < 96 mmol/L): Associated with vomiting, metabolic alkalosis, or chronic respiratory acidosis.

- Hyperchloremia (Cl⁻ > 106 mmol/L): May indicate dehydration, metabolic acidosis, or renal tubular acidosis.

Exam Tip: Many USMLE questions present electrolyte disturbances in the context of metabolic abnormalities. For instance, a patient with hyponatremia and low plasma osmolality may be exhibiting SIADH, while hyperkalemia with metabolic acidosis suggests renal tubular dysfunction.

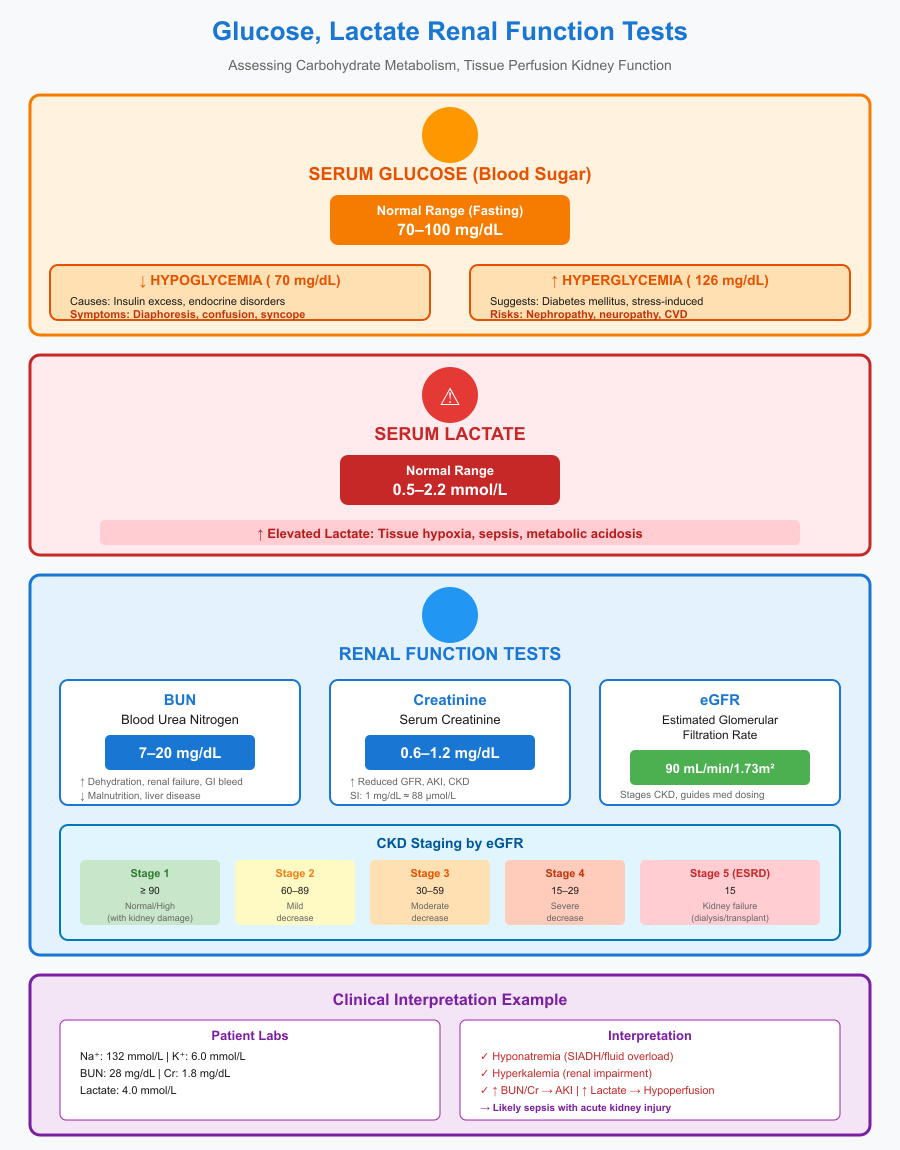

Serum Glucose, Lactate, and Renal Function Test

The metabolic panel extends beyond electrolytes to include critical laboratory parameters that assess carbohydrate metabolism and kidney function. Understanding these markers is essential for identifying metabolic derangements, hypoperfusion, and renal impairment.

1. Glucose (Blood Sugar):

- Reference Range: 70–100 mg/dL (fasting)

- Clinical Relevance:

- Hypoglycemia (< 70 mg/dL): Can result from insulin excess, endocrine disorders, or critical illness. Symptoms include diaphoresis, confusion, and syncope.

- Hyperglycemia (> 126 mg/dL fasting): Suggests diabetes mellitus or stress-induced hyperglycemia. Chronic elevations increase the risk for nephropathy, neuropathy, and cardiovascular disease.

2. Lactate:

- Reference Range: 0.5–2.2 mmol/L

- Clinical Significance:

- Elevated lactate indicates tissue hypoxia, sepsis, or metabolic acidosis.

- Lactate levels guide hemodynamic management and are often used to monitor critical illness progression.

3. Renal Function Tests:

- Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN): 7–20 mg/dL

- High BUN can indicate dehydration, renal failure, or gastrointestinal bleeding.

- Low BUN may reflect malnutrition or liver disease.

- Creatinine: 0.6–1.2 mg/dL (adult)

- Elevated creatinine signals reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR), acute kidney injury, or chronic kidney disease.

- Must consider SI conversion: 1 mg/dL ≈ 88 μmol/L.

- Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR): > 90 mL/min/1.73 m² (normal)

- Used to stage chronic kidney disease (CKD) and guide dosing of renally excreted medications.

Interpretation Example:

A patient presents with sodium 132 mmol/L, potassium 6.0 mmol/L, BUN 28 mg/dL, creatinine 1.8 mg/dL, and lactate 4 mmol/L. Interpretation of these laboratory parameters indicates:

- Hyponatremia (possible SIADH or fluid overload)

- Hyperkalemia (renal impairment or metabolic acidosis)

- Elevated BUN and creatinine suggesting acute kidney injury

- Elevated lactate indicating tissue hypoperfusion, possibly due to sepsis

Clinical Integration: These lab abnormalities together reveal a metabolic derangement involving renal function and perfusion status. Management requires correcting electrolyte imbalances, supporting renal perfusion, and monitoring lactate trends.

Liver Function Tests and Hepatic Laboratory Parameters

Liver function tests (LFTs) are a cornerstone of clinical pathology, providing insight into hepatic health, cellular integrity, and biliary function. Accurate interpretation of ALT, AST, bilirubin, and alkaline phosphatase helps differentiate hepatocellular injury from cholestatic disease, guides diagnosis, and informs management decisions. Understanding normal laboratory parameters, reference ranges, and patterns of abnormality is essential for both clinical practice and USMLE/NBME exam success.

ALT, AST, and Patterns of Hepatocellular Injury

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) are enzymes released into the bloodstream following hepatocyte injury. Elevated levels indicate damage to liver cells from inflammation, toxins, infection, or ischemia.

Normal Laboratory Reference Ranges:

- ALT: 7–56 U/L

- AST: 10–40 U/L

Interpretation of Abnormal Patterns:

- Hepatocellular Injury Pattern:

- Both AST and ALT are elevated, often with ALT > AST.

- Typical causes:

- Viral hepatitis (e.g., hepatitis A, B, C)

- Drug-induced liver injury (acetaminophen, statins)

- Autoimmune hepatitis

- Example: A patient presents with fatigue and jaundice. ALT = 450 U/L, AST = 380 U/L. The predominant hepatocellular pattern suggests acute viral hepatitis.

- AST:ALT Ratio Considerations:

- AST > ALT (ratio >2:1): Classic in alcoholic liver disease

- ALT > AST: Suggests non-alcoholic fatty liver disease or viral hepatitis

- Mild Elevations (<2x normal):

- May be incidental, related to metabolic syndrome, medication, or minor hepatic stress.

- Requires correlation with bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, and clinical context.

Clinical Integration:

AST and ALT elevations should not be interpreted in isolation. They provide information on hepatocellular integrity, but additional laboratory parameters and patient history are necessary for definitive diagnosis.

Bilirubin and Alkaline Phosphatase Interpretation

Bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) help assess biliary excretion, cholestasis, and hemolysis. Their patterns distinguish hepatocellular disease from cholestatic disease.

Normal Laboratory Reference Ranges:

- Total Bilirubin: 0.1–1.2 mg/dL

- Direct (conjugated): 0.0–0.3 mg/dL

- Indirect (unconjugated): 0.2–0.8 mg/dL

- Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP): 44–147 U/L

Interpretation Patterns:

- Hepatocellular Pattern:

- Elevated ALT and AST with mild to moderate elevation in ALP.

- Bilirubin may increase if liver injury impairs conjugation or excretion.

- Example: ALT = 320 U/L, AST = 300 U/L, ALP = 120 U/L, bilirubin = 2.5 mg/dL → acute hepatitis.

- Cholestatic Pattern:

- ALP is predominantly elevated, often >2x normal, sometimes accompanied by mild AST/ALT elevation.

- Causes:

- Bile duct obstruction (gallstones, tumors)

- Primary biliary cholangitis or primary sclerosing cholangitis

- Bilirubin increases in post-hepatic obstruction, leading to jaundice.

- Example: ALP = 480 U/L, ALT = 80 U/L, AST = 70 U/L, bilirubin = 4.0 mg/dL → suggestive of extrahepatic biliary obstruction.

- Isolated Hyperbilirubinemia:

- Unconjugated bilirubin elevation: Hemolysis, Gilbert syndrome

- Conjugated bilirubin elevation: Hepatocellular dysfunction or biliary obstruction

Exam Tip:

USMLE and NBME questions frequently present liver function patterns rather than single lab abnormalities. Recognizing the combination of AST/ALT, ALP, and bilirubin patterns allows rapid differentiation between hepatocellular versus cholestatic liver disease.

Clinical Examples and Integration

Example 1 – Viral Hepatitis (Hepatocellular Pattern):

- ALT = 550 U/L, AST = 500 U/L, ALP = 130 U/L, bilirubin = 3.2 mg/dL

- Interpretation: Predominantly hepatocellular injury; pattern consistent with viral hepatitis. Clinical correlation confirms fatigue, jaundice, and elevated viral serologies.

Example 2 – Cholestatic Disease:

- ALP = 500 U/L, ALT = 100 U/L, AST = 90 U/L, bilirubin = 4.5 mg/dL

- Interpretation: Cholestatic pattern; likely bile duct obstruction. Imaging confirms gallstones obstructing the common bile duct.

Example 3 – Alcoholic Liver Disease:

- AST = 160 U/L, ALT = 70 U/L (AST:ALT > 2:1), ALP = 120 U/L, bilirubin = 1.5 mg/dL

- Interpretation: Classic alcoholic hepatocellular pattern, correlating with history of chronic alcohol use.

Endocrine and Hormonal Laboratory Values

Endocrine function profoundly influences metabolic homeostasis, growth, reproduction, and stress response. Accurate interpretation of hormonal laboratory values is essential for diagnosing thyroid disorders, adrenal insufficiency or excess, and growth-related abnormalities. Knowledge of normal reference ranges, laboratory parameters, and laboratory values allows clinicians to detect subtle hormonal imbalances and apply them in clinical practice and exam scenarios.

Thyroid Function Tests

Thyroid hormones regulate metabolism, cardiovascular function, and growth. The primary laboratory parameters used to assess thyroid function include thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and free thyroxine (free T4). Understanding reference ranges and the relationship between TSH and T4 is critical for differentiating hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, and subclinical thyroid disorders.

Normal Laboratory Reference Ranges:

- TSH: 0.4–4.0 mIU/L

- Free T4: 0.8–1.8 ng/dL

Interpretation Patterns:

- Primary Hypothyroidism:

- TSH: elevated (>4.0 mIU/L)

- Free T4: low (<0.8 ng/dL)

- Example: A patient presents with fatigue, weight gain, and cold intolerance. TSH = 12 mIU/L, free T4 = 0.6 ng/dL → consistent with primary hypothyroidism, most commonly due to Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.

- Subclinical Hypothyroidism:

- TSH: mildly elevated (4.5–10 mIU/L)

- Free T4: normal (0.8–1.8 ng/dL)

- Clinical significance: Often asymptomatic but may progress to overt hypothyroidism, particularly in autoimmune thyroid disease.

- Primary Hyperthyroidism:

- TSH: suppressed (<0.1 mIU/L)

- Free T4: elevated (>1.8 ng/dL)

- Example: Graves’ disease presents with weight loss, palpitations, and tremors. Lab values show TSH = 0.01 mIU/L, free T4 = 3.0 ng/dL → confirms primary hyperthyroidism.

- Secondary (Central) Hypo/Hyperthyroidism:

- Pituitary or hypothalamic disorders may cause abnormal TSH with discordant T4 levels.

Clinical Note:

TSH is the most sensitive marker for primary thyroid disease, but free T4 and clinical presentation must always be interpreted together. USMLE/NBME questions frequently present lab patterns rather than single abnormal values, emphasizing the importance of understanding TSH-T4 relationships.

Endocrine and Hormonal Laboratory Values

Endocrine function profoundly influences metabolic homeostasis, growth, reproduction, and stress response. Accurate interpretation of hormonal laboratory values is essential for diagnosing thyroid disorders, adrenal insufficiency or excess, and growth-related abnormalities. Knowledge of normal reference ranges, laboratory parameters, and laboratory values allows clinicians to detect subtle hormonal imbalances and apply them in clinical practice and exam scenarios.

Thyroid Function Tests

Thyroid hormones regulate metabolism, cardiovascular function, and growth. The primary laboratory parameters used to assess thyroid function include thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and free thyroxine (free T4). Understanding reference ranges and the relationship between TSH and T4 is critical for differentiating hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, and subclinical thyroid disorders.

Normal Laboratory Reference Ranges:

- TSH: 0.4–4.0 mIU/L

- Free T4: 0.8–1.8 ng/dL

Interpretation Patterns:

- Primary Hypothyroidism:

- TSH: elevated (>4.0 mIU/L)

- Free T4: low (<0.8 ng/dL)

- Example: A patient presents with fatigue, weight gain, and cold intolerance. TSH = 12 mIU/L, free T4 = 0.6 ng/dL → consistent with primary hypothyroidism, most commonly due to Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.

- Subclinical Hypothyroidism:

- TSH: mildly elevated (4.5–10 mIU/L)

- Free T4: normal (0.8–1.8 ng/dL)

- Clinical significance: Often asymptomatic but may progress to overt hypothyroidism, particularly in autoimmune thyroid disease.

- Primary Hyperthyroidism:

- TSH: suppressed (<0.1 mIU/L)

- Free T4: elevated (>1.8 ng/dL)

- Example: Graves’ disease presents with weight loss, palpitations, and tremors. Lab values show TSH = 0.01 mIU/L, free T4 = 3.0 ng/dL → confirms primary hyperthyroidism.

- Secondary (Central) Hypo/Hyperthyroidism:

- Pituitary or hypothalamic disorders may cause abnormal TSH with discordant T4 levels.

Clinical Note:

TSH is the most sensitive marker for primary thyroid disease, but free T4 and clinical presentation must always be interpreted together. USMLE/NBME questions frequently present lab patterns rather than single abnormal values, emphasizing the importance of understanding TSH-T4 relationships.

Cortisol, ACTH, and Growth Hormone Levels

The adrenal and pituitary axes play essential roles in stress response, metabolism, and growth. Evaluating cortisol, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), and growth hormone (GH) provides insight into adrenal insufficiency, Cushing’s syndrome, and growth disorders.

Normal Laboratory Reference Ranges:

- Serum Cortisol (Morning, 8 AM): 5–23 μg/dL

- Plasma ACTH: 10–60 pg/mL

- Growth Hormone (GH): <10 ng/mL (pulsatile, often requires stimulation testing)

Interpretation Patterns:

- Primary Adrenal Insufficiency (Addison’s Disease):

- Cortisol: low (<5 μg/dL)

- ACTH: elevated (>60 pg/mL)

- Example: Patient presents with fatigue, hypotension, and hyperpigmentation. Laboratory values: cortisol = 3 μg/dL, ACTH = 120 pg/mL → primary adrenal insufficiency.

- Secondary Adrenal Insufficiency:

- Cortisol: low (<5 μg/dL)

- ACTH: low or inappropriately normal

- Cause: Pituitary insufficiency or hypothalamic disease.

- Cushing’s Syndrome (Excess Cortisol):

- Cortisol: elevated (>23 μg/dL, may require 24-hour urine or dexamethasone suppression testing)

- ACTH: depends on etiology (pituitary vs adrenal vs ectopic)

- Growth Hormone Disorders:

- GH is pulsatile; random measurement is limited.

- Deficiency: Short stature, delayed puberty; confirmed by stimulation tests.

- Excess: Acromegaly in adults or gigantism in children; laboratory evaluation often includes IGF-1 levels, which reflect GH activity.

Clinical Example (Exam-style):

A USMLE question presents a patient with truncal obesity, moon facies, and elevated morning cortisol (28 μg/dL). ACTH = 15 pg/mL. Interpretation: ACTH-independent Cushing’s syndrome, likely adrenal in origin. Understanding these laboratory parameters allows correct classification of adrenal disorders on exams.

Integration and Systematic Interpretation

To accurately interpret endocrine laboratory values:

- Consider the axis: Hypothalamic-pituitary-target organ relationships determine expected lab patterns.

- Compare multiple hormones: Evaluate TSH with free T4, cortisol with ACTH, GH with IGF-1.

- Assess circadian and pulsatile variation: Cortisol and GH fluctuate during the day; interpret results in context.

- Recognize patterns for exam questions: USMLE/NBME often test recognition of classic lab patterns rather than isolated numbers.

Example Integration:

- TSH low, free T4 high → primary hyperthyroidism

- Cortisol high, ACTH low → adrenal Cushing’s

- GH deficiency → short stature with low IGF-1 → pediatric growth disorder

This systematic approach ensures clinical accuracy, exam readiness, and proper application of endocrine laboratory parameters.

Quick-Reference Tips for USMLE and NBME Exam Success

Mastering NBME and USMLE lab values is not only about memorizing numbers—it’s about understanding patterns, clinical relevance, and exam strategy. Efficient interpretation of laboratory parameters can differentiate between closely related conditions, ensure correct diagnosis, and optimize performance on high-stakes exams. This section highlights high-yield labs, common pitfalls, and methods for applying lab values in clinical scenarios.

High-Yield Lab Values and Exam Patterns

Certain laboratory values are consistently tested on USMLE and NBME exams due to their clinical significance and diagnostic utility. Recognizing exam patterns and focusing on high-yield labs can improve accuracy under time pressure.

1. Frequently Tested Laboratory Parameters:

- Hematology:

- RBC, hemoglobin, hematocrit, platelets

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) in inflammatory disorders

- High-yield interpretation: Anemia subtypes, thrombocytopenia, and coagulation abnormalities.

- Metabolic Panel:

- Electrolytes (Na⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, HCO₃⁻)

- BUN, creatinine, estimated GFR for renal function

- Glucose, lactate for metabolic status

- Exam relevance: Acid-base disturbances, renal failure, and metabolic emergencies.

- Liver Function Tests:

- ALT, AST, ALP, bilirubin

- Patterns distinguish hepatocellular vs cholestatic disease.

- Endocrine/Hormonal Labs:

- TSH, free T4, cortisol, ACTH, growth hormone

- Frequently tested in thyroid, adrenal, and pituitary disorders.

2. Recognizing Exam Patterns:

- Lab Value Combinations: USMLE/NBME often test lab patterns rather than isolated values.

- Example: Elevated ALT and AST with normal ALP → hepatocellular injury.

- Elevated ALP with mild ALT/AST → cholestatic process.

- Trend Interpretation: Recognize sequential changes in labs over time.

- Example: Rising BUN with stable creatinine may indicate prerenal azotemia.

- Ratio and Calculated Values: Some exams require AST:ALT ratio, anion gap, or corrected calcium interpretation.

- Example: AST:ALT > 2:1 → alcoholic hepatitis.

Common Pitfalls in Interpreting Lab Results

Even when familiar with reference ranges, exam takers can make errors if lab interpretation lacks context. Awareness of common pitfalls in laboratory medicine can improve accuracy.

1. Ignoring Units and Reference Ranges:

- Labs may be reported in conventional units vs SI units. Misreading units can result in incorrect interpretation.

- Example: Glucose 5.5 mmol/L is normal, but 5.5 mg/dL would indicate severe hypoglycemia.

2. Overlooking Clinical Context:

- Isolated lab abnormalities can be misleading without patient history or symptoms.

- Example: Mildly elevated AST in an asymptomatic patient may be due to muscle injury, not liver disease.

3. Misinterpreting Mild vs Significant Abnormalities:

- Not all deviations outside reference ranges are clinically urgent.

- Strategy: Assess magnitude, trends, and relevance to diagnosis.

4. Confusing Lab Patterns Across Systems:

- Electrolyte disturbances can mimic endocrine disorders.

- Example: Hyperkalemia with metabolic acidosis may suggest renal tubular dysfunction, not primary adrenal pathology.

5. Exam Pressure Errors:

- Time constraints may cause oversight of subtle abnormalities.

- Strategy: Develop a systematic approach, focusing on high-yield labs and patterns.

Using Lab Values to Guide Clinical Diagnosis

Correctly applying laboratory values transforms numerical data into diagnostic insight. USMLE/NBME questions frequently present case-based scenarios, requiring interpretation of labs within a clinical context.

Stepwise Approach:

- Verify Units and Reference Ranges:

- Confirm whether results are in SI units or conventional units to avoid misinterpretation.

- Identify Abnormal Values:

- Highlight labs outside reference ranges, including mild deviations that may signal early disease.

- Determine the Pattern:

- Group labs by system: hepatocellular vs cholestatic, metabolic vs electrolyte imbalance, endocrine axis evaluation.

- Integrate with Clinical Features:

- Combine lab patterns with symptoms, vital signs, and history to narrow differential diagnosis.

- Example: A patient with fatigue, hyperpigmentation, low cortisol, and high ACTH → primary adrenal insufficiency.

- Apply Exam Strategies:

- Focus on high-yield lab combinations, recognize classic patterns, and avoid overanalyzing rare deviations.

- Use process-of-elimination by cross-checking labs against common NBME/USMLE scenarios.

Example Clinical Scenario:

- Labs: Sodium 128 mmol/L, potassium 6.2 mmol/L, BUN 32 mg/dL, creatinine 1.7 mg/dL, lactate 3.5 mmol/L

- Interpretation: Hyponatremia with hyperkalemia suggests adrenal insufficiency; elevated BUN/creatinine indicates renal involvement; elevated lactate may reflect hypoperfusion. Pattern recognition leads to accurate diagnosis

Conclusion

Mastering NBME and USMLE lab values is a fundamental component of both clinical practice and exam success. Throughout this guide, we have explored the breadth of laboratory parameters, from hematological markers like RBCs, hemoglobin, and platelets, to metabolic panels, liver function tests, and endocrine hormones such as TSH, cortisol, and growth hormone. Each set of reference ranges and laboratory values carries specific clinical significance, serving as a roadmap for diagnosis, monitoring, and patient management.

Understanding the patterns of abnormality—whether hepatocellular versus cholestatic liver injury, electrolyte imbalances, or endocrine dysfunction—is just as important as memorizing normal ranges. Recognizing these patterns allows clinicians and exam takers alike to translate numerical data into actionable clinical insights, making connections between lab values, physiological changes, and patient presentation.

Equally vital is the systematic approach to interpreting lab results, which encompasses verifying units, identifying deviations, integrating multiple parameters, and contextualizing findings within the patient’s clinical scenario. This methodology reduces errors, improves diagnostic accuracy, and prepares candidates for USMLE and NBME-style case-based questions, which often emphasize pattern recognition over rote memorization.

Moreover, familiarity with common pitfalls—such as misreading units, ignoring reference ranges, or overlooking trends—is crucial. Laboratory values are not standalone indicators; their interpretation depends on careful clinical correlation, knowledge of physiology, and understanding of underlying pathophysiology.

Ultimately, proficiency in NBME and USMLE lab values empowers healthcare professionals to make evidence-based decisions, enhances patient care, and builds confidence in both clinical practice and high-stakes examination settings. By integrating laboratory parameters, reference ranges, and systematic interpretation strategies, clinicians and students alike can navigate complex diagnostic challenges with precision, clarity, and efficiency.

Key Takeaway: Laboratory values are more than numbers—they are diagnostic tools, clinical signposts, and exam essentials. Mastery comes from understanding their significance, recognizing patterns, and applying this knowledge in context, ensuring both academic and professional success.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does USMLE give lab values?

Yes. The USMLE exams, especially Step 1 and Step 2 CK, frequently present laboratory values within clinical case vignettes. These values are used to test interpretation skills, pattern recognition, and diagnostic reasoning rather than rote memorization alone.

What’s the difference between USMLE and NBME?

- USMLE (United States Medical Licensing Examination): A three-step exam required for medical licensure in the U.S., assessing medical knowledge, clinical reasoning, and patient management skills.

- NBME (National Board of Medical Examiners): The organization that creates and administers USMLE exams and other assessment tools. While the NBME also provides practice exams and subject tests, it is not an exam itself; USMLE is the licensing exam.

Do you have to memorize lab values for Step 1?

Yes, but selectively. Step 1 expects you to know common, high-yield lab values (e.g., hemoglobin, electrolytes, liver enzymes, TSH, cortisol) and recognize patterns of abnormality in clinical scenarios. Rare or highly specialized values are usually provided within the vignette.

What are the 5 basic laboratory tests?

The five basic laboratory tests often considered essential in initial evaluation are:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): Evaluates RBCs, WBCs, hemoglobin, hematocrit, and platelets.

- Basic Metabolic Panel (BMP): Measures electrolytes, glucose, and renal function (BUN, creatinine).

- Liver Function Tests (LFTs): ALT, AST, ALP, bilirubin for hepatic evaluation.

- Urinalysis: Assesses kidney function, infection, and metabolic abnormalities.

- Coagulation Panel: PT, aPTT, and INR to assess hemostasis and bleeding risk.