Gabapentin Mechanism of Action Explained: How It Treats Neuropathic Pain

Introduction to Gabapentin

Gabapentin is a widely used pharmacological agent in modern clinical practice, primarily recognized for its role in managing neuropathic pain and as an adjunct in seizure control. Its introduction into therapeutic use represented a significant advancement in the treatment of complex pain states and partial-onset seizures, offering clinicians and nursing staff an alternative to traditional antiepileptic drugs. Unlike conventional medications that directly mimic neurotransmitters or inhibit neuronal firing, gabapentin’s effects are mediated through modulation of specific neuronal pathways, which influences both nerve excitability and pain transmission. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for nursing professionals tasked with monitoring efficacy, managing adverse effects, and educating patients on safe and effective use.

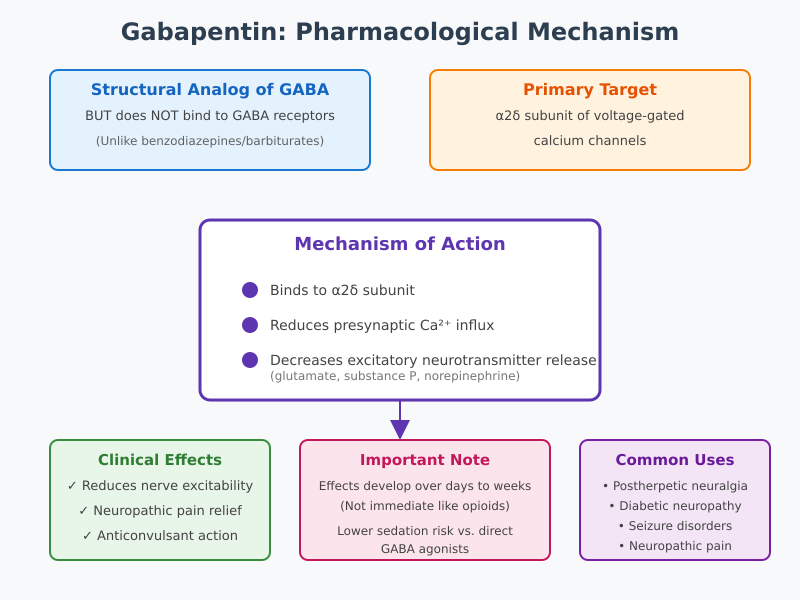

Historically, gabapentin was synthesized as a structural analog of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system. Despite this structural similarity, gabapentin does not directly activate GABA receptors, a distinction that is crucial for understanding its pharmacological profile. Its therapeutic action involves binding to subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels in the nervous system, which modulates neurotransmitter release and reduces hyperexcitability in neurons. This mechanism underlies gabapentin’s utility in alleviating nerve pain associated with conditions such as diabetic neuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia, and other peripheral neuropathic pain syndromes.

From a nursing perspective, a thorough grasp of gabapentin’s pharmacology extends beyond theoretical knowledge. Nurses play a pivotal role in assessing patient response to gabapentin therapy, monitoring for common and serious adverse effects, adjusting dosing regimens in collaboration with prescribers, and providing patient education to optimize adherence and pain relief. Recognizing the distinction between gabapentin’s structural relation to GABA and its actual sites of action enables nurses to interpret therapeutic outcomes accurately and anticipate potential complications in diverse patient populations, including those with renal impairment or comorbid seizure disorders.

In the context of pain management, gabapentin illustrates how targeted pharmacological interventions can influence the transmission of pain signals, offering measurable relief in chronic neuropathic pain conditions. Its use exemplifies the intersection of neuroscience, pharmacology, and nursing practice, highlighting the importance of evidence-based understanding for safe and effective patient care. This article provides a comprehensive exploration of gabapentin, detailing its chemical properties, mechanisms of action, clinical applications, and nursing considerations, with the goal of enhancing both theoretical knowledge and practical competence in managing neuropathic pain and seizure disorders.

Pharmacological Basis of Gabapentin

Chemical Structure and Relation to GABA

Gabapentin is a structural analog of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), the principal inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system. Chemically, gabapentin is a cyclohexyl GABA derivative, designed to mimic certain aspects of GABA’s structure while retaining unique pharmacological properties. Despite this structural similarity, gabapentin does not bind directly to GABA receptors, a fact that distinguishes it from classical GABAergic agents such as benzodiazepines or barbiturates. This distinction is clinically significant because the therapeutic effects of gabapentin, including its ability to treat neuropathic pain and modulate seizures, occur through mechanisms independent of direct GABA receptor activation.

The misconception that gabapentin functions like GABA itself is common, particularly among patients who assume it acts as a central nervous system depressant. In reality, gabapentin’s sites of action are more selective, targeting specific subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord and supraspinal regions. By influencing neuronal excitability indirectly rather than mimicking inhibitory neurotransmission, gabapentin provides analgesic and anticonvulsant effects with a lower risk of sedation compared to direct GABA agonists.

Example: In patients with postherpetic neuralgia, the effect of gabapentin in reducing nerve pain does not involve GABA receptor activation. Instead, its modulation of neurotransmitter release in sensory neurons diminishes hyperexcitability, leading to measurable pain relief.

Neurotransmitter Modulation

One of the key pharmacological properties of gabapentin is its ability to modulate neurotransmitter activity. Pain transmission in neuropathic states is often amplified by excessive release of excitatory neurotransmitters such as glutamate, substance P, and norepinephrine. These neurotransmitters enhance the firing of action potentials along nociceptive pathways, contributing to chronic pain conditions. Gabapentin reduces the release of excitatory neurotransmitters by binding to the alpha-2-delta subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels, thereby dampening presynaptic calcium influx that normally triggers neurotransmitter exocytosis.

While gabapentin does not directly activate GABA receptors, it indirectly enhances inhibitory signaling in certain neural circuits. This indirect influence can increase overall GABAergic tone, reducing hyperexcitability of neurons involved in neuropathic pain and seizure propagation. In essence, gabapentin shifts the balance between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission, stabilizing neural networks that would otherwise propagate aberrant pain signals or seizure activity.

Example: In a rat model of neuropathic pain, gabapentin administration was shown to decrease glutamate release in dorsal horn neurons, resulting in reduced pain responses. Translating this to clinical practice, patients with diabetic neuropathy often experience decreased pain intensity and improved functional outcomes when treated with gabapentin.

Clinical Significance in Reducing Nerve Excitability

Understanding gabapentin’s pharmacological basis is crucial for nursing practice because its effects on neurotransmission underpin both pain relief and seizure control. By modulating calcium influx and neurotransmitter release, gabapentin reduces the excitability of overactive neurons in peripheral and central pain pathways. This property is particularly beneficial in chronic neuropathic pain conditions, where conventional analgesics may be ineffective.

Nursing considerations include monitoring patient response to gabapentin therapy, educating patients about the delayed onset of maximal analgesic effects, and recognizing that gabapentin’s action differs from sedative or opioid-based pain medicines. Unlike medications that provide immediate symptomatic relief, gabapentin’s effectiveness develops over several days to weeks, reflecting the time required for modulation of neuronal excitability and neurotransmitter release.

Example in practice: For a patient with postherpetic neuralgia, initial doses of gabapentin may produce modest pain relief. Over time, as gabapentin reduces presynaptic excitatory signaling, the patient reports improved pain control, illustrating the clinical relevance of understanding its mechanism rather than assuming direct sedative action.

Interaction with Voltage-Gated Calcium Channels

Targeted Subunits and Mechanism

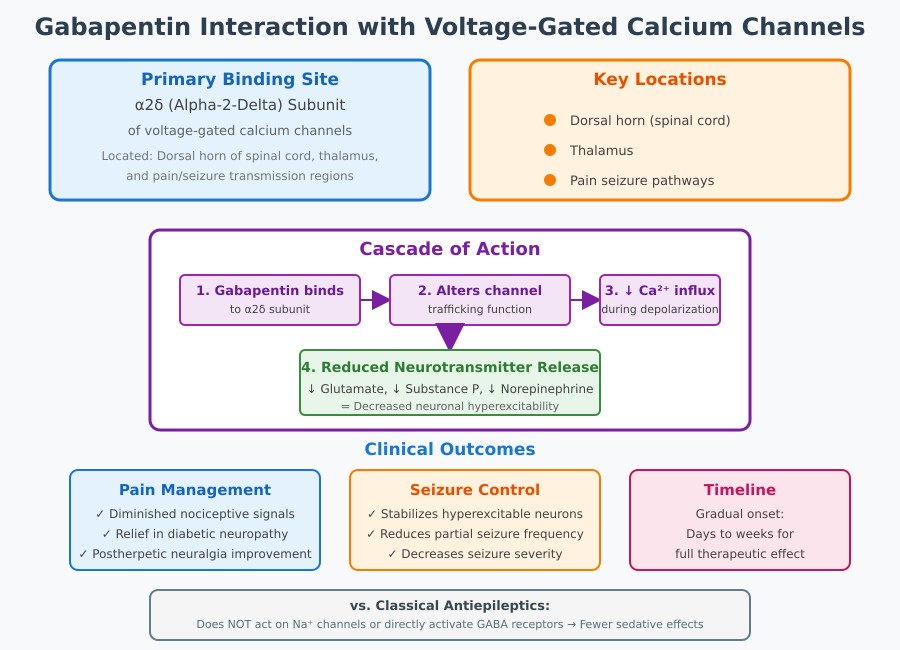

A central mechanism underlying gabapentin’s therapeutic effects involves its selective interaction with voltage-gated calcium channels in the nervous system. Specifically, gabapentin binds to the alpha-2-delta subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels, a component critical for regulating calcium influx at presynaptic terminals. These channels are highly expressed in neurons within the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, thalamus, and other regions implicated in the transmission of pain signals and seizure activity.

Binding to the alpha-2-delta subunit alters channel trafficking and function, thereby reducing calcium entry into neurons during depolarization. This mechanism prevents the excessive release of excitatory neurotransmitters, including glutamate and substance P, which are responsible for amplifying nociceptive signals in neuropathic pain conditions. By dampening this presynaptic calcium influx, gabapentin decreases neuronal hyperexcitability—a hallmark of chronic neuropathic pain and certain seizure disorders.

Example: In patients with diabetic neuropathy, gabapentin reduces the firing of overactive sensory neurons by inhibiting glutamate release. This modulation of presynaptic signaling diminishes the intensity of pain associated with peripheral nerve injury, illustrating a direct link between the alpha-2-delta subunit mechanism and clinical pain relief.

Clinical Implications

The clinical significance of gabapentin’s interaction with voltage-gated calcium channels extends to both pain management and seizure control. By reducing the release of excitatory neurotransmitters, gabapentin effectively decreases the propagation of action potentials along nociceptive pathways, resulting in diminished neuropathic pain states. In seizure disorders, the same mechanism contributes to stabilization of hyperexcitable neuronal networks, thereby reducing the frequency and severity of partial seizures.

From a nursing perspective, understanding this mechanism helps in anticipating patient response and optimizing therapy. Nurses should recognize that the therapeutic effect of gabapentin is gradual, reflecting the time required to modulate neurotransmitter release and neuronal excitability. This is particularly important when educating patients who may expect immediate analgesic or anticonvulsant effects.

Example: In postherpetic neuralgia, patients often report progressive pain relief over days to weeks of gabapentin therapy. This delay aligns with the drug’s effect on calcium channel subunits rather than direct receptor activation, emphasizing the importance of adherence and monitoring during initial therapy.

Differences from Classical Antiepileptic Drugs

Gabapentin’s mechanism is distinct from classical antiepileptic drugs, such as phenytoin, carbamazepine, or valproate. Traditional antiepileptics typically act by directly inhibiting voltage-gated sodium channels or enhancing GABA receptor activity, resulting in immediate suppression of neuronal firing. In contrast, gabapentin does not act on sodium channels or directly activate GABA receptors. Its selective binding to the alpha-2-delta subunit represents a targeted approach, allowing modulation of excitatory neurotransmission without broad CNS depression.

This distinction is clinically relevant for nursing care, as gabapentin is often associated with fewer sedative effects compared to other antiepileptic drugs. Patients may experience improvements in pain relief and seizure control with reduced cognitive impairment or drowsiness, which can influence patient safety, adherence, and quality of life.

Example: A patient with chronic neuropathic pain and a history of epilepsy may tolerate gabapentin better than a traditional antiepileptic drug, experiencing fewer CNS-related side effects while still achieving meaningful pain relief and seizure reduction.

Clinical Applications of Gabapentin

Indications for Neuropathic Pain

Gabapentin is widely utilized in the treatment of neuropathic pain, providing relief for patients suffering from conditions where traditional analgesics may be insufficient. Among the most common indications are diabetic neuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia, and other neuropathic syndromes such as complex regional pain syndrome and chemotherapy-induced neuropathy. Its effectiveness is attributed to the action of gabapentin in neuropathic pain, where it reduces the excitability of overactive neurons and dampens the transmission of pain signals in both peripheral and central pathways.

Example: A patient with diabetic neuropathy may report burning, tingling, or shooting pain in the feet. Administration of gabapentin reduces the intensity of these pain sensations by modulating voltage-gated calcium channels in sensory neurons, ultimately decreasing the release of excitatory neurotransmitters like glutamate and substance P. Similarly, in postherpetic neuralgia, gabapentin helps alleviate persistent pain following shingles infection, improving patient mobility and quality of life.

Evidence-Based Comparison with Pregabalin

Both gabapentin and pregabalin target the alpha-2-delta subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels to reduce excitatory neurotransmitter release. However, pregabalin exhibits higher bioavailability and more predictable pharmacokinetics, allowing for linear absorption and a more consistent therapeutic effect. Clinical trials suggest that gabapentin in neuropathic pain is similarly effective to pregabalin in conditions like diabetic neuropathy and postherpetic neuralgia, though onset of pain relief may be slower.

Example: In a randomized trial comparing gabapentin and pregabalin for diabetic neuropathy, patients in both groups reported significant reductions in neuropathic pain scores. Gabapentin required titration over several days to weeks to achieve maximal effect, whereas pregabalin provided slightly faster relief due to its pharmacokinetic profile. From a nursing perspective, this highlights the importance of patient education regarding delayed onset of action and adherence during titration.

Dose Ranges and Titration Considerations

Gabapentin dosing is individualized based on patient response, renal function, and tolerance. Typical starting doses for neuropathic pain begin at 300 mg once daily, gradually increasing to 900–3600 mg per day, divided into multiple doses. Titration is essential to minimize side effects of gabapentin, including dizziness, somnolence, and peripheral edema. Slow titration also allows clinicians and nursing staff to monitor patient response, optimize pain relief, and ensure safe therapy.

Example: A patient initiating gabapentin therapy for postherpetic neuralgia may start with 300 mg at bedtime, gradually increased to 900 mg per day in three divided doses. Nurses monitor for adverse effects, adjust dosing schedules as indicated, and educate the patient on consistent gabapentin administration to achieve optimal outcomes.

Use in Seizure Disorders

Gabapentin is also approved as an adjunctive therapy for partial seizures in adults and pediatric populations. Its efficacy in seizure suppression stems from its ability to modulate voltage-gated calcium channels and reduce neuronal hyperexcitability without directly acting on sodium channels or GABA receptors. This mechanistic rationale for seizure suppression makes gabapentin a valuable option for patients requiring an anticonvulsant drug with minimal sedative or cognitive side effects.

Example: In a patient with focal epilepsy unresponsive to monotherapy, gabapentin may be added to an existing regimen. By targeting calcium channel subunits, gabapentin stabilizes neuronal firing, decreases the frequency of seizures, and is generally well tolerated. Nurses are responsible for monitoring seizure frequency, adherence, and potential drug interactions when gabapentin is used alongside other anticonvulsants.

Safety, Adverse Effects, and Nursing Considerations

Common Adverse Effects

Gabapentin is generally well tolerated, but like all pharmacologic agents, it can produce adverse effects that require careful monitoring. The most frequently reported reactions include dizziness, somnolence, ataxia, and peripheral edema, which are usually dose-dependent and more pronounced during the initial titration period. These side effects can impact patient safety, particularly in older adults or individuals with compromised mobility, increasing the risk of falls and injury.

Nursing assessment and monitoring strategies involve close observation during the early phases of therapy and at each dose adjustment. Nurses should evaluate patient-reported symptoms such as lightheadedness, excessive drowsiness, or unsteady gait, and document any functional impairments. Patient education is essential: advising individuals to rise slowly from sitting or lying positions, avoid driving or operating heavy machinery during initial therapy, and report persistent or worsening symptoms.

Example: A patient with diabetic neuropathy started on gabapentin may experience mild dizziness after the first dose. Nursing staff can implement safety measures, including bedside assistance and fall precautions, while monitoring for symptom improvement as the body adjusts to the gabapentin administration.

Serious Adverse Effects

Although uncommon, gabapentin may induce serious reactions that necessitate immediate intervention. These include hypersensitivity reactions, severe central nervous system (CNS) depression, or profound respiratory compromise in patients with multiple CNS depressants. Clinicians should also be alert to signs of gabapentin withdrawal in patients discontinuing therapy abruptly, which may precipitate increased seizure activity or heightened neuropathic pain.

Guidelines for therapy discontinuation recommend gradual tapering over at least one week or longer, depending on the patient’s dose and clinical response, to minimize withdrawal symptoms and ensure safety. Nurses play a critical role in observing for early signs of toxicity, counseling patients on safe discontinuation, and coordinating with prescribers for appropriate adjustments.

Example: A patient on high-dose gabapentin for postherpetic neuralgia who develops severe somnolence and confusion should be assessed promptly. Nursing staff must alert the prescriber, monitor vital signs, and consider temporary suspension or gradual dose reduction to prevent complications.

Drug Interactions and Precautions

Gabapentin has relatively few direct pharmacokinetic interactions but can exhibit significant drug interactions that influence therapeutic efficacy and safety. Concomitant use with CNS depressants, including opioids, benzodiazepines, or alcohol, can potentiate sedation and increase fall risk. Antacids containing aluminum or magnesium can reduce the bioavailability of gabapentin, necessitating careful timing of administration. Additionally, gabapentin may interact with other anticonvulsants, altering seizure control and requiring monitoring of gabapentin therapy outcomes.

Patient-specific considerations are critical in ensuring safe gabapentin use. Renal impairment reduces clearance, requiring dose adjustments to prevent accumulation and toxicity. In pregnancy, gabapentin should be used cautiously, balancing maternal benefit with potential fetal risk. Comorbidities such as respiratory disease, CNS depression, or seizure disorders influence both dosing and monitoring strategies. Nursing staff are responsible for assessing baseline renal function, monitoring for adverse effects, and educating patients on potential drug interactions to maximize safety.

Example: A patient with chronic neuropathic pain and concurrent opioid use may experience excessive drowsiness. Nurses should coordinate with the prescriber to adjust the dose of gabapentin, stagger medication timing, and implement safety precautions to prevent falls and maintain optimal pain management.

Optimizing Gabapentin Therapy

Effective management of gabapentin therapy requires more than simply prescribing the medication; it involves a coordinated approach that balances pain relief, seizure control, and minimization of adverse effects. Optimization is particularly important in neuropathic pain conditions and seizure disorders, where patient response can be variable, and adherence is often influenced by side effects, dosing complexity, and individual patient factors.

Strategies to Improve Adherence and Minimize Adverse Effects

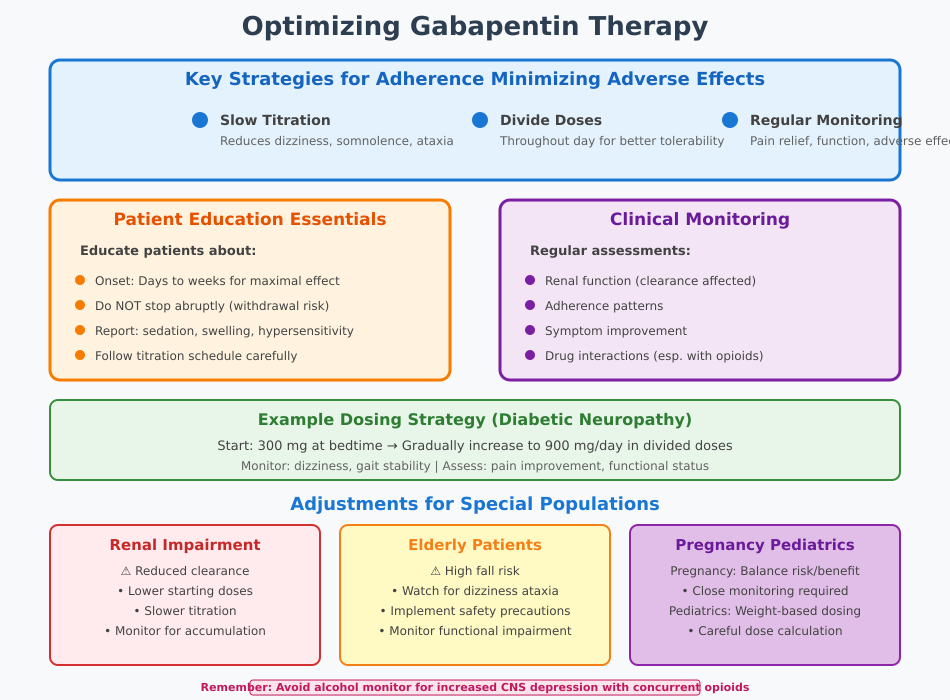

One of the key challenges in gabapentin therapy is ensuring adherence while minimizing side effects of gabapentin. Slow titration of the dose of gabapentin is a widely recommended strategy to reduce dizziness, somnolence, and ataxia, which are the most commonly reported adverse reactions. Dividing doses throughout the day rather than using a single large dose can also enhance tolerability and improve gabapentin administration compliance.

Regular monitoring of patient response is critical. Nurses should evaluate both subjective reports of pain relief or seizure control and objective measures such as functional improvement and frequency of adverse effects. Adjustments can be made based on clinical response, renal function, or interactions with other medications.

Example: A patient with diabetic neuropathy may start on 300 mg at bedtime, gradually increased to 900 mg/day in divided doses. Nursing staff monitor for dizziness and gait instability while assessing improvements in pain associated with neuropathy. Counseling patients about expected onset of therapeutic effects encourages adherence and reduces premature discontinuation due to perceived ineffectiveness.

Patient Education and Monitoring in Clinical Practice

Patient education is a cornerstone of optimized gabapentin use. Nurses should inform patients that maximal pain relief or seizure reduction may take several days to weeks, and that abrupt cessation can lead to gabapentin withdrawal symptoms or exacerbation of neuropathic pain. Patients should be taught to report adverse effects such as unusual sedation, swelling, or signs of hypersensitivity, and to follow the prescribed titration schedule carefully.

Monitoring in clinical practice includes regular assessment of renal function, adherence patterns, symptom improvement, and potential drug interactions. Documentation of patient response, adverse events, and interventions helps guide ongoing therapy adjustments and ensures patient safety.

Example: In a patient taking gabapentin alongside opioids for chronic neuropathic pain, nurses may provide a schedule to stagger medications, monitor for increased sedation, and educate the patient to avoid alcohol. This approach minimizes CNS depression while maintaining gabapentin’s effectiveness.

Adjustments in Special Populations

Special populations require tailored approaches to gabapentin therapy. In patients with renal impairment, clearance of gabapentin is reduced, necessitating lower starting doses and slower titration to avoid accumulation and toxicity. Pregnant patients may require close monitoring to balance maternal benefit with potential fetal risk, while pediatric dosing must be carefully calculated based on weight and clinical response.

Elderly patients are particularly susceptible to adverse effects, including dizziness and ataxia, which can increase fall risk. In these patients, nurses may implement safety precautions, adjust dosing schedules, and monitor closely for functional impairments. For individuals with comorbid seizure disorders, gabapentin dosing must be coordinated with other anticonvulsants to maintain therapeutic efficacy without excessive CNS depression.

Example: A patient with chronic pain conditions and reduced renal function may start gabapentin at a lower dose, with incremental titration and frequent assessment of pain relief and sedation. Nursing staff provide education on monitoring for swelling, dizziness, and adherence to ensure safe and effective therapy.

Conclusion

Gabapentin represents a unique pharmacologic approach in the management of neuropathic pain and seizure disorders. Its mechanism of action of gabapentin is distinct from classical antiepileptic drugs, relying primarily on selective binding to the subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels. This interaction reduces release of excitatory neurotransmitters, modulates neurotransmitter activity, and indirectly enhances inhibitory signaling within the central nervous system. These actions stabilize hyperexcitable neurons, diminish pain signals, and provide effective control of both chronic pain and partial seizure activity.

Clinically, gabapentin has proven effective in conditions such as diabetic neuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia, and other neuropathic pain conditions, offering patients meaningful pain relief while maintaining a favorable safety profile. Its gradual onset of action, dose-dependent adverse effects, and requirement for careful gabapentin administration highlight the importance of individualized therapy and monitoring. Nursing professionals play a pivotal role in optimizing therapy through patient education, titration guidance, assessment for side effects of gabapentin, and vigilance for drug interactions that may impact bioavailability of gabapentin or overall efficacy.

Key takeaways for safe and effective use include:

- Understanding the sites of action and mechanism of action of gabapentin ensures accurate interpretation of patient response and expectations for therapy.

- Slow titration and monitoring can minimize common adverse effects such as dizziness, somnolence, and ataxia, while enhancing pain relief and seizure control.

- Tailoring therapy to special populations, including patients with renal impairment, elderly individuals, or those on concurrent CNS depressants, is essential for safety.

- Educating patients on adherence, potential gabapentin withdrawal, and expected onset of pain relief fosters engagement and optimizes therapeutic outcomes.

- Nursing surveillance and documentation are critical for identifying early signs of complications, ensuring gabapentin use is both safe and effective in clinical practice.

Ultimately, gabapentin exemplifies how targeted pharmacologic therapy can improve pain management and seizure control while requiring an integrated, evidence-based nursing approach. By understanding its mechanisms, clinical applications, and safety considerations, nurses can enhance patient outcomes, ensure adherence, and contribute to high-quality, safe care in the treatment of neuropathic pain and seizure disorders.

Frequently Asked Questions

What exactly does gabapentin do?

Gabapentin reduces nerve hyperexcitability by binding to the alpha-2-delta subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels, which decreases the release of excitatory neurotransmitters such as glutamate and substance P. Clinically, this helps treat neuropathic pain (e.g., diabetic neuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia) and serves as an adjunctive therapy for partial seizures. It stabilizes overactive neurons without directly acting on sodium channels or GABA receptors.

What is the action of gabapentin on GABA?

Despite being a structural analog of GABA, gabapentin does not directly activate GABA receptors. Its action is indirect: by modulating voltage-gated calcium channels, it reduces excitatory neurotransmission and can enhance inhibitory signaling within neural circuits, indirectly supporting GABAergic tone and stabilizing neurons.

What is the classification of gabapentin?

Gabapentin is classified as an anticonvulsant drug (antiepileptic drug) and is also considered a neuropathic pain modulator. It is structurally a GABA analog, but its therapeutic effects are independent of direct GABA receptor activation.

Can you take hydroxyzine with gabapentin?

Caution is advised when combining hydroxyzine (an antihistamine with sedative properties) and gabapentin. Both drugs can cause CNS depression, including drowsiness, dizziness, and sedation. Concurrent use may increase the risk of impaired coordination or falls. If co-administration is necessary, it should be closely monitored, and patients should be advised to avoid activities requiring alertness until they understand how the combination affects them.