Family Health Assessment in Family Nursing: Using Genogram and Ecomap as Family Assessment Tools for Effective Nursing Assessment

Family health assessment is a cornerstone of family nursing, offering a structured approach to understanding how health and illness are experienced within the family unit. Just as a comprehensive nursing assessment guides care for individual patients, family health assessment provides insight into the broader context of family dynamics, relationships, and social environment that shape health outcomes. At its core, the process emphasizes that individuals and families cannot be fully understood in isolation; instead, they exist within systems of connection, responsibility, and support that influence both risks and strengths.

Central to this approach are visual assessment tools such as the genogram and the ecomap. A genogram functions as a detailed family diagram, capturing at least three generations of family structure, health conditions, and relational patterns. An ecomap, in contrast, highlights the family’s interactions with external systems and community resources, mapping supportive, neutral, or stressful relationships in the broader social environment. When used together, genograms and ecomaps provide complementary perspectives: one focused on health history and family relationships, the other on external influences and support networks.

These tools have practical value across nursing practice, social work, and family therapy. They enable healthcare providers to recognize hereditary health patterns, identify unmet family needs, and assess available community resources. By translating complex family information into a visual representation, genograms and ecomaps help nurses, social workers, and other health professionals engage more effectively with families, promote health, and design interventions that reflect the realities of family life.

This article explores the foundations of family health assessment, the role of genograms and ecomaps, and how these tools enhance nursing practice. Through clear definitions, examples, and templates, it demonstrates how visual representations of family systems can deepen understanding, strengthen communication, and support better outcomes in both individual and family care.

What is Family Health Assessment in Family Nursing?

A family health assessment is a structured, systematic process nurses use to gather information about the household or family unit — who lives in the home, how members relate to one another, key elements of medical and psychosocial history, daily routines, caregiving roles, and links to external supports. Unlike an individual medical history that focuses only on one patient, a family-centred assessment situates that person in the context of family relationships and the social environment, producing a picture that supports family-centred care planning and shared decision-making. Frameworks such as the Calgary Family Assessment Model (CFAM) help clinicians organize structural, functional and developmental dimensions of the family during assessment.

In clinical practice the assessment is typically gathered through a combination of interview, observation, and review of records. Nurses document a concise household roster, salient medical histories, daily caregiving arrangements, communication and decision-making patterns, and known contacts with community or formal services. The output is a usable snapshot that informs immediate nursing actions (e.g., education, safety planning) and longer-term coordination (e.g., referrals to home health or social services).

Why is Family Health Assessment Important?

Family context shapes health in ways that are often decisive for outcomes. Below are the principal reasons family assessment is essential, with examples of how the information changes nursing decisions:

- Reveals hereditary and intergenerational health risks.

Mapping family history (for example with a genogram) exposes clusters of disease — early-onset cardiovascular disease, familial diabetes, hereditary cancers, or multigenerational mental-health problems — which influence screening, early intervention and genetic counselling recommendations. For instance, a nurse who documents multiple first-degree relatives with early myocardial infarctions will prioritize cardiovascular risk management and referral for family screening. - Clarifies caregiving capacity and role distribution.

Knowing who provides hands-on care (medication management, transport, ADLs), who holds decision-making authority, and who is likely to be available after discharge prevents unrealistic plans. A discharge plan that assumes family members can administer complex wound care will fail if the family assessment shows no available caregiver or limited health literacy. - Detects social determinants that influence recovery and adherence.

Problems such as food insecurity, unstable housing, transportation barriers, or lack of health insurance are not medical diagnoses but are common drivers of readmission, non-adherence, and delayed recovery. Identifying these through the assessment allows early linkages to community resources and targeted referrals. - Exposes family strengths that can be leveraged in care.

The same assessment identifies protective factors — a reliable neighbor, religious community supports, or an organizing family member — which clinicians can use to design realistic interventions (e.g., training a committed relative to manage medications). - Improves communication and shared decision-making.

When families understand clinical goals and feel heard, they participate more effectively. Patient- and family-centred approaches to transitions of care have been shown to improve numerous outcomes including satisfaction, participation and (in some settings) clinical results. Integrating the family assessment into care conversations supports that partnership. - Supports safety and risk identification.

Assessing family dynamics can surface issues such as intimate partner violence, elder neglect, or caregiver burnout — important safety signals that require immediate action and referral.

How Does Family Health Impact Individual Health?

Family influence operates through multiple, overlapping mechanisms. Understanding these pathways helps nurses translate assessment findings into targeted actions.

- Biological / genetic transmission.

Shared genes explain predisposition to many conditions. A structured family health assessment highlights these patterns so clinicians can plan age-appropriate screening and consider genetic counselling referrals. (Genograms are the standard visual tool for this purpose.) - Behavioral transmission and shared routines.

Eating habits, activity levels, tobacco or alcohol use, and sleep routines are typically shared or modeled within families. Interventions that target family routines (for example, family dietary counselling for diabetic control) are often more effective than individual-only approaches. - Psychosocial climate and stress exposure.

Chronic conflict, caregiving strain, or poor communication increase allostatic load and raise risk for depression, anxiety and stress-related physical illness. Conversely, positive emotional support reduces stress and improves coping. - Material and access factors.

Housing stability, income, transport options and proximity to health services determine whether prescriptions are filled, specialist appointments are kept, and rehabilitative care is possible. These are often best revealed by exploring the family’s connections to community resources (for which an ecomap is practical). - Role and identity effects.

Family roles (primary caregiver, breadwinner, decision-maker) create obligations and constraints that influence choices about care. A working single parent, for example, may be unable to attend daytime clinic visits — a fact that should change scheduling or referral plans.

Clinical implication: when nurses translate family assessment findings into care plans they increase the likelihood that recommendations are feasible, acceptable, and safe in the family’s real social environment.

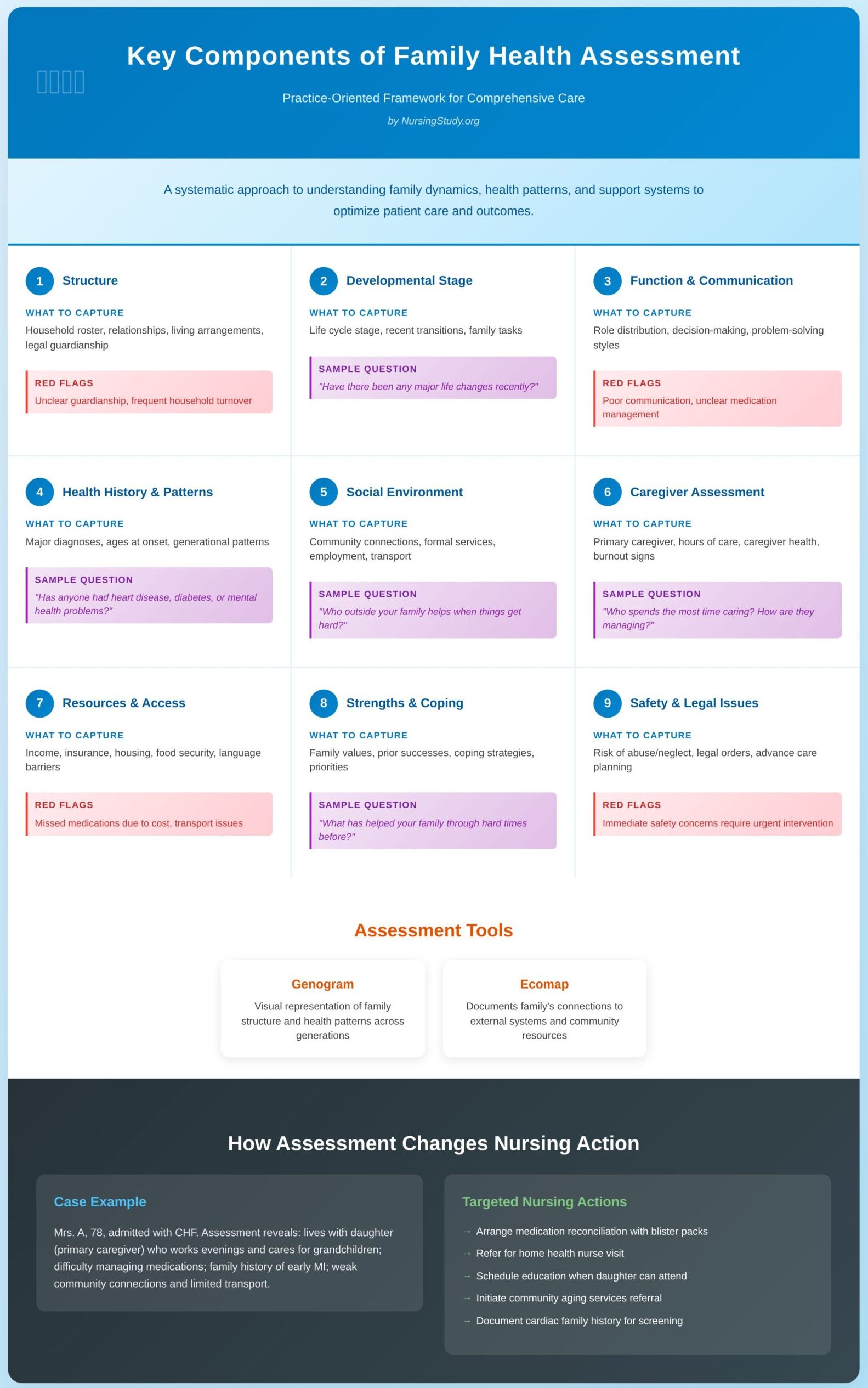

What are the Key Components of Family Health Assessment?

Below is an expanded, practice-oriented breakdown of the domains to include. For each domain I list what to capture, why it matters, red flags, and sample questions the nurse can use in an interview.

1. Structure (who and how they are related)

- What to capture: household roster (names, ages), biological and non-biological relationships (step-parents, foster carers), living arrangements, legal guardianship, significant others who provide support but live elsewhere.

- Why it matters: clarifies who will deliver care, legal decision-makers, and potential sources of support or conflict.

- Red flags: unclear guardianship for vulnerable adults, frequent household turnover, multiple non-related cohabitants carrying caregiving roles.

- Sample prompts: “Who lives in your home? Who helps you at home? Are there any step- or half-siblings or others who are involved in care?”

2. Developmental stage & life-course tasks

- What to capture: life cycle stage (young parents, families with adolescents, multigenerational household), recent transitions (birth, death, job loss, migration).

- Why it matters: predicts typical stressors and support needs; for example, adolescent transitions often shift supervision responsibilities.

- Sample prompts: “Have there been any major life changes for your family recently?” “What are the biggest tasks your family is managing right now?”

3. Function — roles, communication & routines

- What to capture: who manages medications, finances, meal preparation, who makes medical decisions, problem-solving styles, emotional support patterns.

- Why it matters: functional strengths (clear task-division, collaborative decision-making) can be harnessed; dysfunction (poor communication, deception) signals need for family therapy or social work referral.

- Red flags: inconsistent caregivers, unclear medication management, avoidance of health topics.

- Sample prompts: “Who helps remind you to take your medications?” “How do you and your family usually make big health decisions?”

4. Health history & patterns across generations

- What to capture: major diagnoses in family members, ages at onset (early vs typical), patterns of mental-health conditions, substance use, congenital conditions.

- Why it matters: informs screening and preventive counselling; repeated patterns may suggest inherited conditions or shared environmental exposures.

- Sample prompts: “Has anyone in your family had heart disease, diabetes, cancer, or severe mental health problems? At what ages were they diagnosed?”

5. Social environment & external systems (community connections)

- What to capture: social supports (friends, faith communities), formal services (home healthcare, social services, schools), employment, transport, neighbourhood safety. Ecomaps are the preferred visual tool to represent these ties and their quality.

- Why it matters: identifies gaps that affect recovery (no transport for follow-ups), community supports to leverage (church volunteers), and potential service partners.

- Sample prompts: “Who outside your family helps when things get hard?” “Are you connected to any community or religious groups?”

6. Caregiver assessment & burden

- What to capture: who provides day-to-day care, hours of caregiving, caregiver health, respite availability, signs of burnout.

- Why it matters: caregiver stress predicts worse outcomes for both caregiver and patient; early referral for respite or home care can prevent crisis.

- Sample prompts: “Who spends the most time caring for [patient]? How are they managing?” “Do they need help with tasks or time off?”

7. Resources, access & social determinants

- What to capture: income, insurance, housing quality, food security, legal needs, literacy, language barriers.

- Why it matters: these factors directly affect ability to follow through with care plans.

- Red flags: missed medication refills due to cost, inability to attend appointments due to transport, unsafe housing.

8. Strengths, coping and priorities

- What to capture: family values, prior successes, preferred coping strategies, present priorities (e.g., keeping dad at home vs. institutional care).

- Why it matters: build interventions that align with family goals and leverage internal strengths.

- Sample prompts: “What has helped your family through hard times in the past?” “What is most important to you about care right now?”

9. Safety and legal issues

- What to capture: risk of abuse/neglect, legal orders, guardianship, advanced care planning.

- Why it matters: immediate safety concerns require urgent intervention and appropriate documentation.

Illustrative vignette (how a family assessment changes nursing action)

Mrs. A, aged 78, is admitted with congestive heart failure. A family health assessment reveals: she lives with her daughter (primary caregiver) who works evenings and cares for two young grandchildren; the daughter reports difficulty managing multiple medications; there is a history of early myocardial infarction in the patient’s father and brother; the family has weak connections to community home-help services and limited transport. From this assessment the nurse:

(1) arranges a medication reconciliation with blister packs,

(2) refers for a home health nurse visit,

(3) prioritizes education sessions at times when the daughter can attend, and

(4) initiates referral to a community aging services program for respite support.

The genogram records the cardiac family history for follow-up screening of relatives; the ecomap documents the weak ties to formal services that require strengthening. These targeted actions reduce the risk of early readmission and address both medical and social drivers of health.

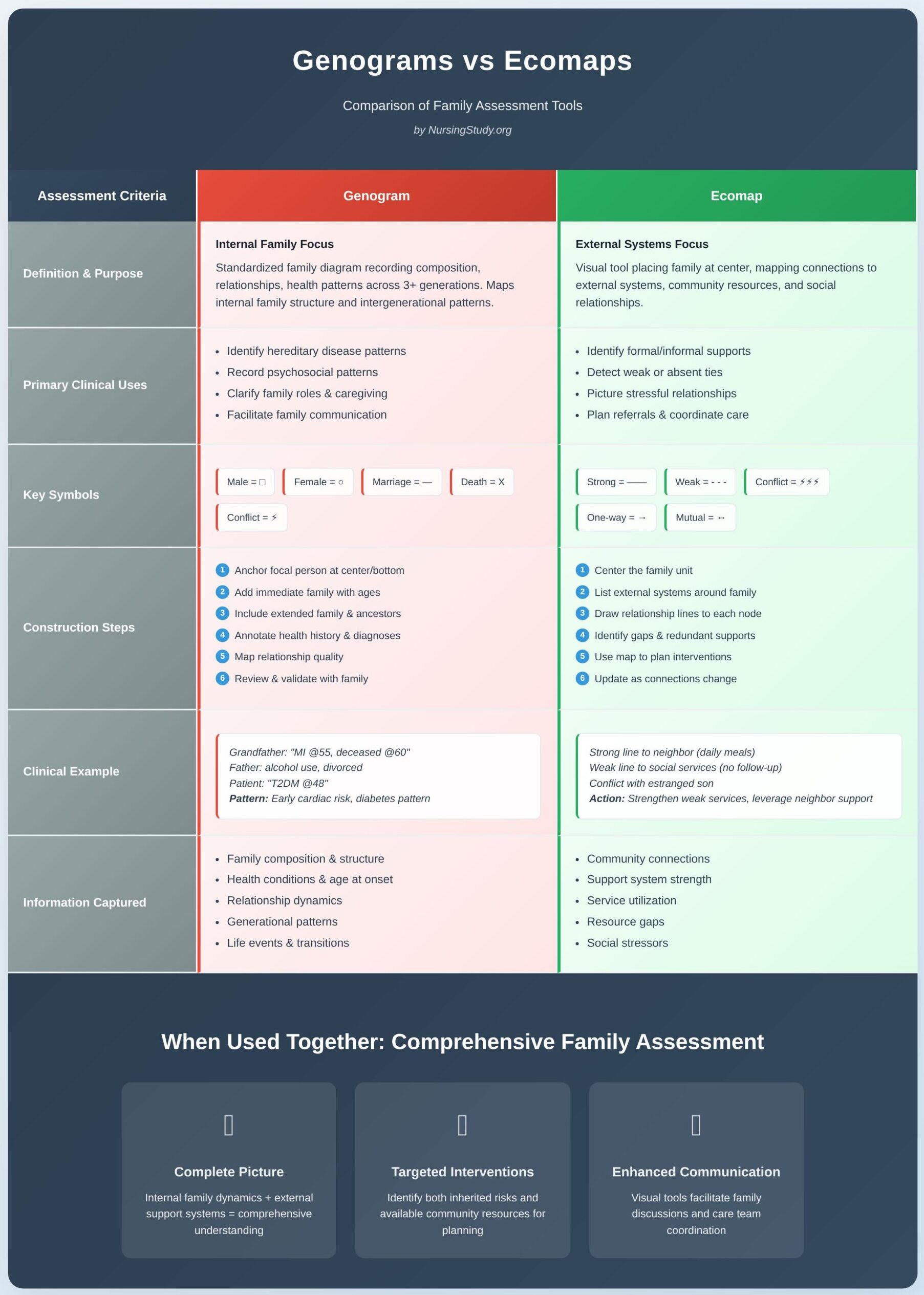

What are Genograms and Ecomaps?

Genograms and ecomaps are complementary visual assessment tools used in family nursing, social work, family therapy, and public health to represent family structure, health history, relationships, and the family’s connections to the wider social environment. Both tools convert interview data into compact diagrams that make patterns, strengths and gaps immediately visible for clinicians and families.

In practice they are most powerful when used together: the genogram maps the family’s internal structure and intergenerational health patterns, while the ecomap depicts the family’s external supports, services and social relationships.

What is a Genogram and How is it Used in Family Nursing?

Definition and purpose

A genogram is a standardized family diagram that records family composition (biological and non-biological members), relationship types, major life events, and salient medical and psychosocial information across at least three generations. Unlike a simple family tree, a genogram explicitly captures relational dynamics (alliances, conflict, separations), ages or dates (birth, death, age at diagnosis), and health patterns that often recur across generations.

In family nursing, genograms are used to:

- Identify hereditary or familial patterns of disease (e.g., early-onset coronary disease, familial diabetes, hereditary cancers).

- Record psychosocial patterns (e.g., multigenerational substance use, recurrent depression, patterns of divorce).

- Clarify family roles and caregiving relationships relevant to planning care.

- Facilitate communication and shared understanding during assessment, discharge planning, or health promotion.

Common symbols and conventions

Although genogram conventions vary slightly by discipline, clinicians commonly use these elements:

- Male = square, Female = circle.

- Marriage/partnership = horizontal line connecting two symbols; divorce/separation indicated by slashed or broken line through the connection.

- Death = X inside the shape or a diagonal line through the symbol.

- Sibling order = vertical drop lines from the parental connection, left to right by birth order.

- Special markers or abbreviations beside or within symbols to record diagnoses, ages at diagnosis, substance use, suicide, or other clinically relevant events (e.g., “MI @55” or “Dep (dx 2008)”).

- Relational lines between two family members to indicate strong emotional bond, conflict (jagged line), distant/estranged (dashed line), or caregiving relationship (annotation or arrow).

Tip: keep an accompanying legend on the same page so other clinicians can read the chart quickly.

How to build a genogram — step-by-step

- Prepare: gather any prior records and consent. Decide which family members to include and whether to capture three generations (recommended for hereditary pattern detection).

- Anchor the focal person: place the patient/client (the “identified patient”) near the center/bottom so relationships and ancestors can be mapped above.

- Record immediate family: add spouse/partner, children, and household members with ages or dates.

- Add extended family: parents, siblings, grandparents, aunts/uncles — include ages or year of birth and salient diagnoses.

- Annotate health history: next to each symbol add key health conditions and age at onset, psychiatric history, substance use, cause/age of death.

- Map relational quality: add lines/annotations showing alliances, conflict, caregiving roles, or legal guardianship.

- Review and validate with the family: ask for corrections or additions and invite family interpretation — the mapping process itself sparks useful clinical dialogue.

- Document and store appropriately: scan or attach to the record with a short narrative summary and consent note.

Example

A three-generation genogram for a family might show:

- Paternal grandfather: male square, “MI @55, deceased @60.”

- Father: male square, alcohol use (annotated), divorce from mother (slashed line), current spouse with two children.

- Identified patient: female circle, Type 2 diabetes diagnosed at 48 (“T2DM @48”).

Seeing “MI @55” in the elder generation and “T2DM” in multiple relatives immediately flags cardiovascular risk and the need for targeted screening and lifestyle interventions across family members.

Clinical uses and interpretation

- Risk stratification: identify relatives who may benefit from screening or genetic counseling.

- Care planning: understand who is available to provide medication management, transport, or personal care.

- Therapeutic conversations: genogram construction frequently uncovers unspoken history and improves family communication about health risks and caregiving expectations.

What is an Ecomap and What Information Does it Provide?

Definition and purpose

An ecomap (or eco-map) is a visual tool that places the family unit at the center and maps the family’s connections to external systems: extended kin who don’t live in the household, friends, schools, employers, community groups, health services, welfare agencies, and other community resources. The map emphasizes the quality and direction of these relationships so clinicians can see strengths to leverage and stressors that may impede care.

In family nursing, an ecomap is used to:

- Identify formal and informal supports available for care (e.g., church volunteers, community nursing teams, neighbors).

- Detect weak or absent ties that must be addressed for safe discharge (e.g., no one available to assist with ADLs).

- Picture stressful external relationships (e.g., conflict with an in-law providing childcare) that affect family functioning.

- Plan referrals to community resources and coordinate multidisciplinary care.

Symbols and line types

Ecomaps use simple shapes (circles or boxes) for external systems and different line styles to show relationship quality:

- Solid heavy line = strong, supportive relationship (mutual, dependable).

- Thin or dashed line = tenuous or distant relationship.

- Jagged or zigzag line = stressful or conflictual relationship.

- Arrow(s) = direction of influence or flow of resources (one-way dependence vs mutual exchange).

- Double arrow = reciprocal, two-way helpful relationship.

Nodes commonly included: extended family, friends, neighbors, school, workplace, primary care clinic, community health services, religious organizations, benefits agencies, and support groups.

How to construct an ecomap — step-by-step

- Center the family: draw a circle or box for the household (or identify the family by name).

- List external systems: around the family place nodes for institutions and individuals the family interacts with.

- Draw lines to each node: use stylistic conventions to indicate strength, stress, or direction. Add short annotations to explain the nature of each tie (frequency of contact, specific help provided, obstacles).

- Identify gaps and redundant supports: note where there are no links to needed services or where supports overlap.

- Use the map to plan: prioritize referrals, community linkages, or strategies to strengthen weak ties.

Example

A family ecomap for a household with an older adult may show: a strong solid line to a neighbor who brings meals daily (close support), a dashed line to a social services agency that has been contacted but never followed up (weak engagement), a jagged line to an estranged son who refuses to help (stressful tie), and a solid two-way arrow to a church support group that provides transport to appointments. This visual immediately helps clinicians see where to invest effort (e.g., re-establish contact with social services, refer for home health).

How Do Genograms and Ecomaps Differ in Purpose and Structure?

Below are the core contrasts and the ways the tools complement each other in clinical work.

1. Primary focus

- Genogram: internal family structure and intergenerational patterns (who is related to whom, ages, health diagnoses, relationship quality).

- Ecomap: external systems and social environment (who supports the family, what community resources exist, which external ties are stressful or helpful).

2. Temporal emphasis

- Genogram: often spans generations and captures historical patterns across time (age at onset, cause/age of death).

- Ecomap: is typically contemporaneous, showing current social connections and resource flows.

3. Core elements

- Genogram: symbols for individuals, lines for relationships, annotations for diagnoses, and chronology details.

- Ecomap: nodes for systems and institutions, line styles indicating relationship quality/direction, annotations about the frequency and nature of contacts.

4. Typical clinical uses

- Genogram: genetic risk identification, family therapy, exploring patterns of illness/behavior across generations, identifying family caregivers and legal decision-makers.

- Ecomap: discharge planning, community resource mapping, identifying social determinants affecting adherence, coordination of multidisciplinary care.

5. Interpretation and action

- Genogram → prompts screenings, family education, alerts for genetic counseling, or family therapy referral.

- Ecomap → prompts referrals to community services, social work involvement, linkage to transportation, home health, or support groups.

6. Visualization and audience

- Genogram: reads like a pedigree with relational annotations that clinicians and families can review together to discuss health patterns.

- Ecomap: reads like a network diagram showing flows of support — very useful in care coordination meetings and when engaging social services.

Complementary use (combined example)

For discharge planning of a patient with heart failure: a genogram may reveal a family history of early cardiovascular disease and identify that the only available caregiver has chronic back pain (limits caregiving capacity).

The ecomap may show weak ties to home-care agencies and no formal transport options. Together these diagrams justify early referral to home health, enrollment in a cardiac rehabilitation service that offers transport, and education sessions scheduled when the identified caregiver is available.

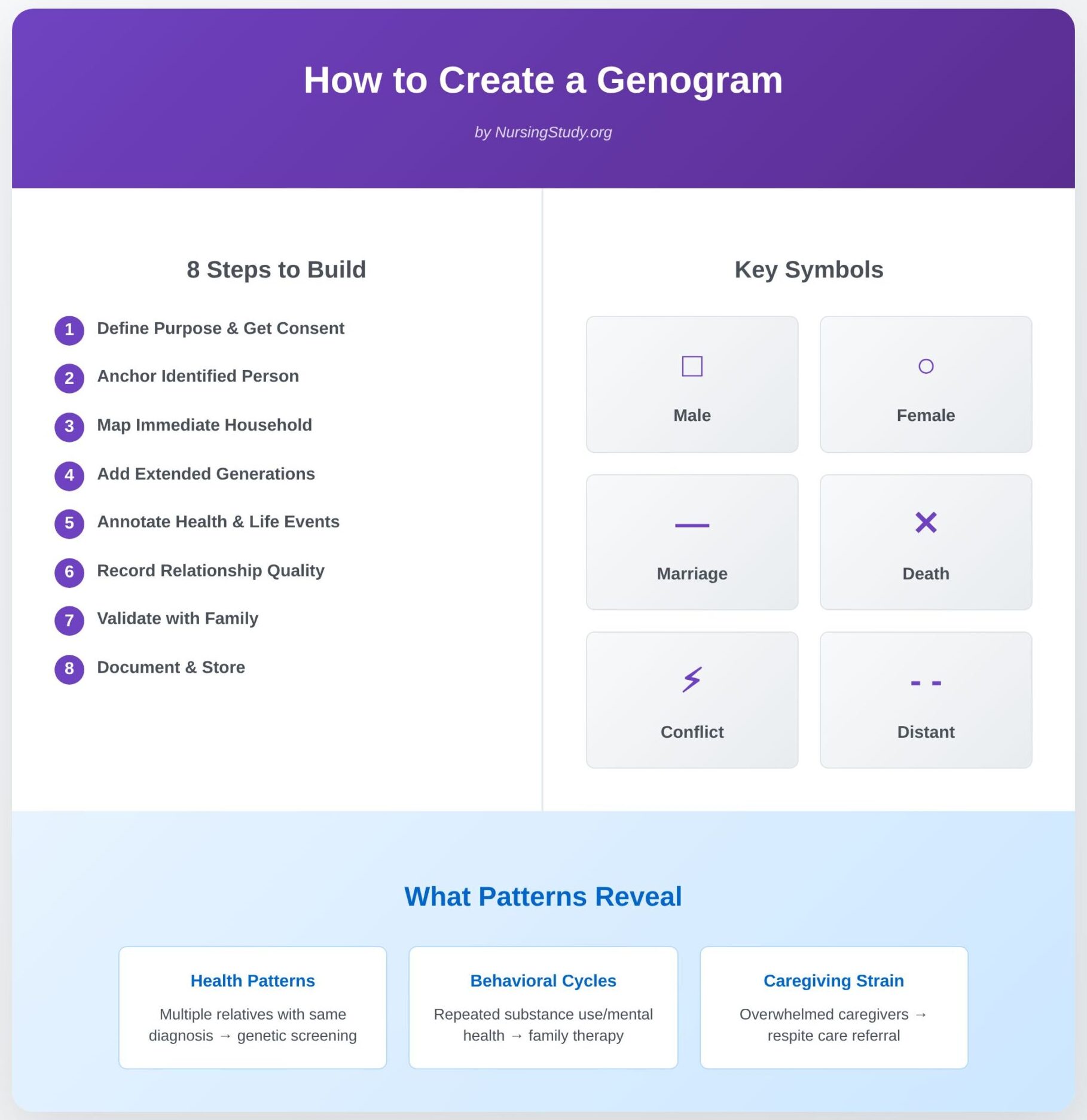

How to Create a Genogram for Family Assessment?

Below is a practical, clinician-focused guide to building a usable three-generation genogram (family diagram) for nursing assessment, followed by the standard symbols to use, the information to capture, and how the diagram reveals family dynamics and health patterns you can act on.

1) Planning & preparation — set the purpose and get consent

- Define the purpose. Decide whether the diagram is for hereditary risk screening, discharge planning, psychosocial assessment, or a combination. A clear purpose focuses what you ask and what you record.

- Obtain consent and explain use. Tell the family why you’re drawing the chart, what you will include, and how it will be stored. Emphasize that the map is a collaborative clinical tool, not a judgemental inventory.

- Gather sources. Prepare to combine (a) family interview data, (b) existing health records, and (c) collateral information (with consent) from other providers or relatives to improve accuracy.

2) Step-by-step construction workflow

- Anchor the identified person. Place the focal patient (often called the identified person) in a central position on the page so you can show ancestors above and descendants below.

- Map the immediate household. Add spouse/partner and cohabitants (names, ages/DoB or current age). Use simple placement so reading order is intuitive (parents above, children below).

- Add extended generations. Extend upward to parents, grandparents, aunts/uncles and sideways for siblings — aim to cover at least three generations when clinically relevant (to reveal intergenerational patterns).

- Annotate key life events and dates. Beside each person record birth year/age, death (with age/ cause if known), and ages at major diagnoses (e.g., “MI @55”, “breast cancer dx 2007”, “Dep dx 2003”). These chronological details are vital for pattern recognition.

- Record relationship quality. Add relational lines and symbols to show marriage, divorce, close bonds, conflict, estrangement or caregiving responsibilities (see symbols below). These qualitative markers are the clinical value of the map.

- Capture psychosocial & behavioral data. Add concise annotations for substance use, mental-health diagnoses, repeated incarceration, adoption, or migration events that affect family function.

- Validate and invite interpretation. Review the draft with the family: ask if dates/labels are correct and invite their view of relationships and important context. The conversation itself is therapeutic and clarifying.

- Record actions and storage. Attach a short narrative summary to the chart and store it in the clinical record per institutional policy (with explicit consent for sensitive items). Note who provided information and any verification limits.

What Symbols are Used in Genograms?

Use a simple legend on every genogram so colleagues can read it quickly. Common, well-accepted conventions include:

- Gender: square = male; circle = female. Use alternative or annotated symbols for non-binary or unspecified identities if needed.

- Marriage / partnership: solid horizontal line joining two symbols.

- Cohabitation / common-law: dotted or dashed horizontal line.

- Divorce / separation: double diagonal slashes or a broken line through the partnership line.

- Death: an “X” inside the symbol or a diagonal line through it; annotate cause and age if known.

- Children order: vertical dropping lines from the parental connection; place children left → right by birth order.

- Pregnancy / miscarriage: a small triangle for pregnancy or a small symbol for miscarriage/termination per local convention.

- Adoption / foster: use dashed-line brackets or specific adoption markers (refer to your institutional legend).

- Relational quality:

- solid heavy line = strong/supportive relationship;

- dashed/weak line = distant/tenuous contact;

- jagged/zigzag line = conflictual or stressful relationship;

- arrow = direction of caregiving or one-way dependence.

Practical tip: always include a short legend on the same page (symbols + date format + abbreviations). This avoids misinterpretation by other clinicians.

What Information Should be Included in a Genogram?

A clinically useful chart is concise but systematic. Capture these elements where available:

- Identifier: name or initials (per local privacy rules), current age or DoB.

- Relationship label: spouse, child, sibling, step-child, foster, etc.

- Key health diagnoses and age at onset: list major chronic illnesses, psychiatric diagnoses, substance-use disorders, congenital conditions, and cancer types with age or year of diagnosis (e.g., “CRC dx 2012, colon resection”).

- Cause and age at death where relevant (e.g., “MI @56, died 1998”) — important for hereditary risk inference.

- Significant life events: incarceration, migration, adoption, abuse, major losses, divorce, long-term unemployment, or severe trauma.

- Functional notes: who manages medications, who is primary caregiver, who provides finances, who makes health decisions.

- Behavioral flags: tobacco, alcohol, substance use, suicide attempts – recorded factually and sensitively.

- Social determinants: housing instability, transport barriers, formal services involved (home health, adult protective services). These may be brief annotations or cross-referenced with an ecomap.

- Source and verification status: who provided the information and whether it’s verified by records (important for clinical reliability).

How Can a Genogram Reveal Family Dynamics and Health Patterns?

A well-constructed diagram does two things: (a) it surfaces recurring biomedical patterns that suggest screening or genetic counseling, and (b) it exposes relational dynamics that affect caregiving, adherence and safety. Below are concrete interpretive cues and the nursing actions they commonly trigger.

A. Detecting intergenerational health patterns (biomedical clustering)

- What to look for: multiple first- or second-degree relatives with the same diagnosis (e.g., several relatives with early-onset coronary disease, stroke, breast/colon cancer, or early dementia).

- Clinical implication: prioritize family screening, consider referral to genetic services or specialized prevention programs, and provide family-level health-promotion education.

Example: paternal grandfather MI @53, father MI @56, and uncle MI @54 → flag for aggressive cardiovascular risk reduction and consider cascade screening for lipid disorders.

B. Recognizing behavioural and psychosocial cycles

- What to look for: repeated patterns of substance use, domestic violence, or repeated psychiatric admissions across generations.

- Clinical implication: refer to mental-health or substance-use services, plan safety assessments, involve social work or family therapy, and consider anticipatory guidance for younger relatives.

Example: two generations with opioid dependence suggest need for family-based addiction services and relapse-prevention planning.

C. Identifying caregiving capacity and role strain

- What to look for: who is listed as primary caregiver, their own health limitations, and multiple dependency chains (e.g., an adult child caring both for an elderly parent and for grandchildren).

- Clinical implication: arrange caregiver assessment, refer for respite/home-help, simplify regimens, and tailor discharge timing to realistic home supports. PubMed

Example: a daughter with chronic back pain is the primary carer → arrange equipment, practical training, or home nursing to prevent breakdown.

D. Mapping relational risk and protective patterns

- What to look for: triangles (where one person mediates conflict between two others), persistent estrangement, enmeshment (very diffuse boundaries), or strongly supportive kin networks.

- Clinical implication: fragile or conflictual relationships may require mediated family meetings or social work support; strong networks can be mobilized to assist with adherence and recovery.

Example: a close-knit extended family with routine shared meals and collective caregiving often provides resilience for chronic disease management; conversely, an estranged primary child increases readmission risk if no backup support exists.

E. Spotting atypical age of onset and red flags

- What to look for: disease onset decades earlier than population norms (e.g., colorectal cancer in 30s, MI in 40s).

- Clinical implication: escalate screening, document the pattern for relatives, and discuss genetic counseling when appropriate.

How to Construct an Ecomap for Family Assessment?

Constructing an ecomap is a structured process designed to capture the graphic representation of a family and its interactions with the external environment. At the center of the diagram, a circle is drawn to represent the family unit, often labeled with the names of individual family members. For a complete family nursing assessment, each member may be included within the central circle, reflecting their role and family structure.

Around this central family symbol, circles or nodes are drawn to represent the family’s most relevant external systems and community resources—such as schools, healthcare providers, workplaces, religious organizations, recreational groups, and community services. These external circles are then connected to the family by lines. The type of line illustrates the quality of the relationship:

- Strong supportive relationship: represented by a solid thick line (e.g., a family with regular access to a trusted social worker).

- Weak or neutral relationship: represented by a thin line (e.g., occasional interaction with neighbors).

- Stressful or conflictual relationship: represented by a jagged line (e.g., conflict with extended relatives about childcare).

- Flow of energy: arrows can be added to show whether support flows toward the family, away from the family, or both.

For example, a nurse and the family may construct an ecomap showing strong ties to their pediatrician, weak ties to school staff, and stressful connections with the father’s employer due to inflexible work schedules. This process helps health professionals identify both strengths and unmet family needs.

What Key Relationships Should be Illustrated in an Ecomap?

An ecomap and genogram together provide complementary views, but the ecomap specifically emphasizes connections beyond the internal family. Key relationships that should be included are both formal support systems (such as hospitals, financial institutions, and community health agencies) and informal support networks (extended family, friends, peers, or faith groups).

For example, a family ecomap of a single-parent household might include:

- A strong supportive line to a grandmother who provides daily childcare.

- A weak line to school staff, reflecting minimal communication about the child’s educational progress.

- A jagged line to a government agency due to difficulties accessing social benefits.

- Arrows showing a significant flow of energy from a local church community that offers food and emotional support.

By mapping these social and personal relationships, the ecomap highlights the family’s social connections and the resources available to address health conditions or psychosocial stressors. It also reveals gaps in support networks, guiding both nursing care and social work interventions.

How Does an Ecomap Highlight Family Interactions with the Community?

The eco-map serves as a visual assessment tool that demonstrates how the family system engages with the wider social environment. While a genogram captures family’s history and patterns within the family, the ecomap extends outward, revealing how the family interacts with external systems.

For example, consider a visual representation of a refugee family newly resettled in a city. Their ecomap might show:

- Strong supportive ties with a resettlement agency and healthcare clinic.

- Neutral ties with schools as they begin adjusting.

- Stressful or conflictual relationships with employers due to language barriers.

- Limited or absent connections to recreational groups, indicating social isolation.

This graphic representation of a family highlights the social support available and the barriers the family faces. It allows healthcare providers and family therapists to assess where community services and support systems can be strengthened. In nursing practice, this helps in assessing family resilience, identifying family strengths, and planning culturally responsive interventions.

What are the Benefits of Using an Ecomap in Family Nursing?

The benefits of incorporating ecomaps into family health assessment are extensive. First, they provide a holistic understanding of how a family may be influenced not only by internal family dynamics but also by their position in the external environment. Second, ecomaps encourage families to visualize and reflect on their own social network, which can improve self-awareness and empower them to utilize existing support systems.

For instance, a family struggling with a child’s chronic illness might not initially recognize the importance of their extended relatives or church group. By using a family ecomap, the nurse and the family can see how these social support systems can be mobilized for respite care, emotional encouragement, or financial assistance. This approach not only helps the family recognize their family strengths, but also provides healthcare teams with a framework to develop effective, family-centered interventions.

From a health promotion perspective, ecomaps are valuable in identifying opportunities to strengthen family’s relationships with community health agencies, schools, and healthcare providers. In working with families, the ecomap becomes more than an assessment tool; it is a collaborative exercise that fosters communication, validates the family’s experience, and provides a visual representation of their connections and challenges.

Ultimately, the genogram and ecomap together create a comprehensive understanding of both the family’s history and its present-day community interactions. This dual approach ensures that individuals and families are supported not only in their medical care but also in their social environment, leading to more effective nursing care and long-term wellbeing.

What are Examples of Genograms and Ecomaps in Practice?

In clinical and community settings, genograms and ecomaps are applied as visual assessment tools that help professionals move beyond surface-level information. Instead of relying solely on verbal histories, these diagrams provide a graphic representation of a family that clarifies hidden patterns, strengths, and vulnerabilities.

For example, a genogram may demonstrate that hypertension, diabetes, or depression appears in multiple members across generations, revealing hereditary risks that might otherwise be overlooked in routine health assessment. In contrast, an eco-map can show whether a family is embedded in strong support networks or isolated from community resources. When combined, the ecomap and genogram reveal both internal family structures and external systems, offering a holistic picture of health influences.

Professionals such as nurses, social workers, and family therapists use these diagrams to tailor interventions. A family nursing assessment that includes both tools ensures that care is responsive not only to biological and medical needs but also to family dynamics and the surrounding social environment.

Can You Provide a Sample Genogram for a Typical Family Structure?

A sample family genogram might involve at least three generations, since this depth reveals meaningful family connections, hereditary patterns, and shifting family roles. Consider a household consisting of a grandmother, her daughter, and the daughter’s own children:

- First generation (grandparents): The grandmother is drawn as a circle, her deceased husband as a square with an “X” through it. The genogram notes his history of hypertension and stroke. The grandmother is annotated with type 2 diabetes.

- Second generation (parents and siblings): The couple’s daughter (circle) is shown married to her husband (square), with a line indicating marital conflict (a jagged line). Her siblings are drawn to the side, one annotated with alcohol dependence, another with asthma.

- Third generation (children): The daughter’s three children are placed below, connected by a sibling line. Annotations reveal that the eldest son struggles with obesity, while the youngest daughter is healthy but has a stressful or conflictual relationship with her father.

This visual representation shows patterns of cardiovascular disease within the family, highlights mental health vulnerabilities, and demonstrates family dynamics through relational symbols. In practice, such a diagram helps healthcare providers anticipate risks, initiate early screenings, and recommend lifestyle changes. It also provides an opening to discuss sensitive issues like substance abuse or strained family’s relationships in a non-threatening way.

What Does a Completed Ecomap Look Like for a Family in Crisis?

An ecomap complements the genogram by shifting focus outward to the family’s social ties and external systems. For a family in crisis—for instance, a single mother with two children facing unemployment and housing instability—the family ecomap would look like this:

- At the center, the family unit (mother and children) is enclosed in a circle.

- Surrounding nodes represent key community services and support systems: a local food bank, the children’s school, the health clinic, extended relatives, a church, and the mother’s previous employer.

- A strong supportive line connects to the food bank, which provides regular groceries.

- A neutral thin line extends to the school, reflecting basic communication but little collaboration.

- A jagged line links the family to the health clinic, showing frustration with delayed care and high bills.

- Extended relatives are drawn with jagged lines too, reflecting stressful or conflictual relationships.

- Arrows show the flow of energy: the family expends much energy managing conflict and health costs, while little energy returns in the form of reliable support.

This visual tool reveals that the family has critical gaps in support networks. The graphic representation of a family in this way allows the nurse and the family to identify not just their stressors but also the community resources that could be strengthened, such as building a better relationship with the school or reconnecting with faith-based groups.

How Can These Examples Inform Family Nursing Interventions?

Concrete examples of genograms and ecomaps inform interventions by making health risks and social barriers visible. For example:

- A genogram showing diabetes and obesity in multiple relatives signals the need for health promotion strategies such as nutritional counseling and exercise programs. It also raises questions about health patterns and how the family may share lifestyle habits that contribute to disease.

- An ecomap of a family in crisis highlights weak ties to community health programs and underdeveloped support systems. A nurse could strengthen these links by referring the family to housing services, connecting them with mental health professionals, or engaging them in parenting support groups.

- When both diagrams are used together, the visual representation provides a holistic family assessment tool: the genogram informs the medical and hereditary perspective, while the eco-map uncovers the family’s social determinants of health.

These tools encourage a collaborative approach to family care. By reviewing the diagrams with individual family members, nurses and social workers help families see their own family strengths, vulnerabilities, and family’s history. In turn, families are more engaged in decision-making and empowered to access the external systems that can improve their health status.

How Do Genograms and Ecomaps Enhance Family Nursing Practice?

In family nursing practice, genograms and ecomaps function as essential assessment tools that deepen understanding of both family systems and their social environment. While traditional nursing assessment often focuses on the individual, these visual tools emphasize the interconnectedness of individuals and families. By mapping family structure, family relationships, and external support systems, they provide a multidimensional framework that guides more effective nursing care.

For example, a family genogram may reveal recurring mental health conditions across generations, such as depression or substance abuse. Recognizing these inherited risks allows nurses to anticipate potential issues and initiate preventive care strategies. An ecomap, on the other hand, may highlight weak or stressful ties with community resources, pointing to gaps in social support that contribute to a family’s vulnerability. Together, the ecomap and genogram offer a visual representation that enhances a nurse’s ability to design holistic interventions tailored to both medical and social needs.

What Insights Can Be Gained from Analyzing Genograms and Ecomaps?

Analyzing these diagrams generates insights that go far beyond what verbal histories typically reveal. Genograms help nurses identify hereditary health patterns, relational stressors, and family roles that influence decision-making. For instance, a three generations genogram and ecomap might show how cardiovascular disease has affected male relatives while also revealing stressful or conflictual relationships between fathers and sons. Such findings can alert nurses to both biological and psychosocial factors shaping the family’s health.

Ecomaps, in contrast, highlight the flow of energy between the family unit and external systems. They uncover whether the family is well-supported by community services or isolated from critical resources. A completed family ecomap may show strong ties to faith-based organizations but strained interactions with healthcare providers due to cost barriers. This information gives health professionals a clearer picture of how the family’s social context affects coping strategies, adherence to treatment, and overall resilience.

How Can Family Nurses Use These Tools to Improve Patient Outcomes?

The integration of genograms and ecomaps into the nursing process strengthens the ability of the nurse and the family to work collaboratively. By presenting graphic representations of a family, nurses foster open conversations that empower families to recognize their own family strengths, vulnerabilities, and family’s history. This shared understanding helps families take ownership of their health decisions.

For example:

- A genogram revealing hereditary diabetes enables the nurse to encourage screening for at-risk individual family members and to promote lifestyle changes across the family unit.

- An eco-map showing limited support networks could prompt referrals to community health programs, housing assistance, or peer support groups.

- When both tools are used together, healthcare providers can address not only medical risk factors but also barriers rooted in the social environment, such as poor access to nutritious food or limited childcare.

Through this approach to family care, nurses can design interventions that are more realistic, sustainable, and culturally appropriate. In the long term, this strengthens family health, reduces hospital readmissions, and supports positive health promotion outcomes.

What Challenges Might a Nurse Face When Using Genograms and Ecomaps?

Despite their benefits, nurses may encounter challenges when applying genograms and ecomaps in practice. One common issue is the difficulty of collecting accurate family information. Some families may withhold details about sensitive topics, such as substance abuse, infertility, or conflictual family’s relationships, due to stigma or distrust. This can limit the completeness of the graphic representation of a family.

Another challenge is time. Constructing a thorough family genogram or eco-map often requires extended interviews, which may be difficult in fast-paced clinical settings. Additionally, some nurses may lack training in interpreting standardized symbols or in facilitating sensitive conversations when drawing diagrams. Cultural differences also play a role—certain traditional family structures or internal family dynamics may not fit neatly into conventional diagram templates, requiring flexibility and cultural competence.

Finally, families may perceive these diagrams as intrusive, particularly when addressing stressful or conflictual relationships or hidden aspects of medical history. Nurses must balance thoroughness with empathy, ensuring that the process helps the family rather than causing discomfort.

To overcome these barriers, ongoing education in family nursing assessment, collaboration with social workers, and the use of templates can streamline the process. By approaching these tools as collaborative exercises rather than rigid tasks, nurses can maximize their effectiveness in working with families.

Conclusion

A family health assessment is not complete without considering both the internal structure of the family and its external connections to the broader social environment. This is where genograms and ecomaps emerge as indispensable family assessment tools. By visually representing patterns of health and illness across generations, genograms help uncover genetic risks, psychosocial dynamics, and recurring themes that influence current and future health outcomes. Similarly, ecomaps provide a snapshot of the family’s interactions with community resources, revealing whether support systems are strong, weak, or sources of stress.

Together, the genogram and ecomap transform traditional nursing assessment into a holistic process—one that considers not only the individual patient but also the family unit as a living system shaped by history, relationships, and external influences. This dual approach equips family nurses to design interventions that are preventive, culturally sensitive, and realistic within the family’s social context.

For instance, a genogram showing multiple cases of hypertension in a family can guide screening and health promotion strategies, while an eco-map highlighting limited ties to healthcare providers may prompt referrals to community clinics or support groups. When used together, these tools not only identify risks but also spotlight strengths, empowering families to recognize their own resources and capabilities.

Of course, challenges exist—from incomplete disclosure of sensitive information to time constraints and cultural differences—but these barriers can be addressed through training, empathy, and collaborative practice. Importantly, both genograms and ecomaps also serve as communication tools: they make invisible dynamics visible, encourage dialogue, and help families actively engage in shaping their own health journey.

Ultimately, the integration of genograms and ecomaps into family nursing assessment represents a shift from individual-focused care to family-centered care. By acknowledging the representation of a family as both a biological and social system, nurses can intervene more effectively, anticipate health risks, and foster resilience. In doing so, they not only improve patient outcomes but also strengthen the well-being of families and communities as a whole.

Frequently Asked Questions

How is a genogram used in family assessment?

A genogram is used to visually map out family structure, health history, and relationships across generations, helping nurses and health professionals identify hereditary health conditions, relational dynamics, and psychosocial patterns that influence current health.

What is ecomap in family assessment?

An ecomap is a visual assessment tool that illustrates how a family interacts with its social environment, including support systems, community resources, and external stressors, highlighting the family’s connections and levels of support.

Which assessment tool would the nurse use to diagram three generations of family members using symbols to denote genealogy?

The nurse would use a genogram, which employs standardized symbols to represent at least three generations of family members and their family relationships.

What are Ecomaps and Genograms may be used in?

Ecomaps and genograms may be used in family nursing, social work, family therapy, and community health to assess family dynamics, identify health risks, explore support networks, and guide interventions for both individuals and families.