Barbara Carper Patterns of Knowing in Nursing: Comprehensive Guide in Nursing Practice

Nursing is both a science and an art, requiring more than technical skill or clinical accuracy. To meet the complex needs of patients, nurses must draw on different forms of knowledge that inform judgment, guide decisions, and shape compassionate care. In 1978, Barbara Carper introduced a framework that has since become foundational in the nursing discipline: the patterns of knowing. These patterns—empirical, ethical, personal, and aesthetic—offer a structured way to understand how nurses come to know what they know and how they apply this knowledge in practice.

The framework emphasizes that nursing cannot be reduced solely to measurable data or standardized procedures. While empirical evidence remains essential for safe and effective interventions, it is equally important for nurses to consider ethical responsibilities, cultivate authentic relationships, and exercise creativity in addressing individual patient situations. Each pattern of knowing contributes a unique perspective, and together they create a more comprehensive understanding of nursing practice.

In today’s clinical environment, where evidence-based practice, patient-centered care, and interprofessional collaboration are emphasized, Carper’s framework remains highly relevant. It provides nurses with a lens for integrating scientific knowledge with ethical reflection, personal awareness, and aesthetic sensitivity. For students and practicing nurses alike, recognizing and applying these patterns supports more thoughtful decision-making and contributes to the delivery of holistic, effective, and compassionate care.

What Are the Carper Fundamental Patterns of Knowing?

The Carper patterns of knowing represent a framework that explains how nurses acquire, organize, and apply different kinds of knowledge in clinical practice. Carper argued that nursing is not limited to technical skills or scientific facts; it also involves ethical reasoning, personal awareness, and an ability to perceive and respond creatively to each clinical situation. By naming these distinct forms of knowledge, the framework helps students and practitioners understand that professional nursing is multidimensional.

For example, a nurse caring for a child with asthma draws on multiple ways of knowing simultaneously: evidence from respiratory guidelines (empirical), sensitivity to the family’s cultural beliefs (ethical), self-awareness in communicating with anxious parents (personal), and an intuitive adjustment of the child’s environment to ease breathing (aesthetic). Each of these actions reflects a pattern of knowing, and together they shape effective care.

Struggling to connect Carper’s patterns to practice?

Our experts can craft a polished assignment.

Who Developed the Carper Patterns of Knowing in Professional Nursing?

The framework was first developed by Barbara Carper in 1978. In her seminal article, Fundamental Patterns of Knowing in Nursing, published in Advances in Nursing Science, Carper identified the need for a systematic way to articulate what counts as knowledge in nursing. She proposed four primary categories — empirical, ethical, personal, and aesthetic — to capture the diverse dimensions of professional practice.

Carper’s contribution was groundbreaking because it challenged the assumption that scientific knowledge alone was sufficient for high-quality nursing care. By highlighting other equally important forms of knowledge, she broadened the philosophical foundation of the nursing discipline. Since then, her framework has been widely cited in nursing literature, taught in schools of nursing worldwide, and used as a basis for curriculum design, reflective practice, and research into knowledge development in nursing.

What Are the Four Patterns of Knowing?

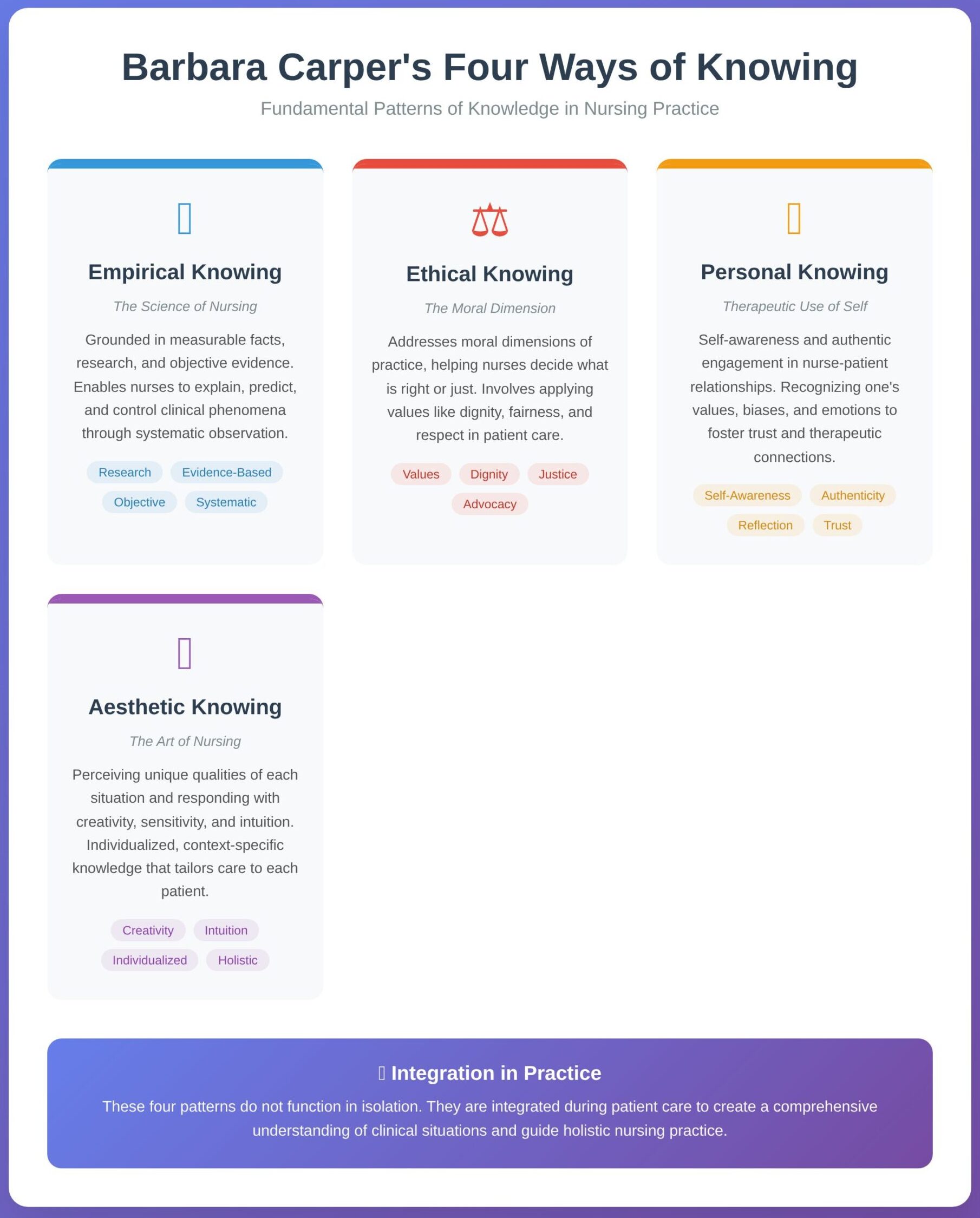

Carper identified four fundamental patterns of knowing, each representing a different way that nurses generate and apply knowledge in practice. These patterns do not function in isolation; rather, they are integrated during patient care to create a fuller understanding of clinical situations.

1. Empirical Knowing

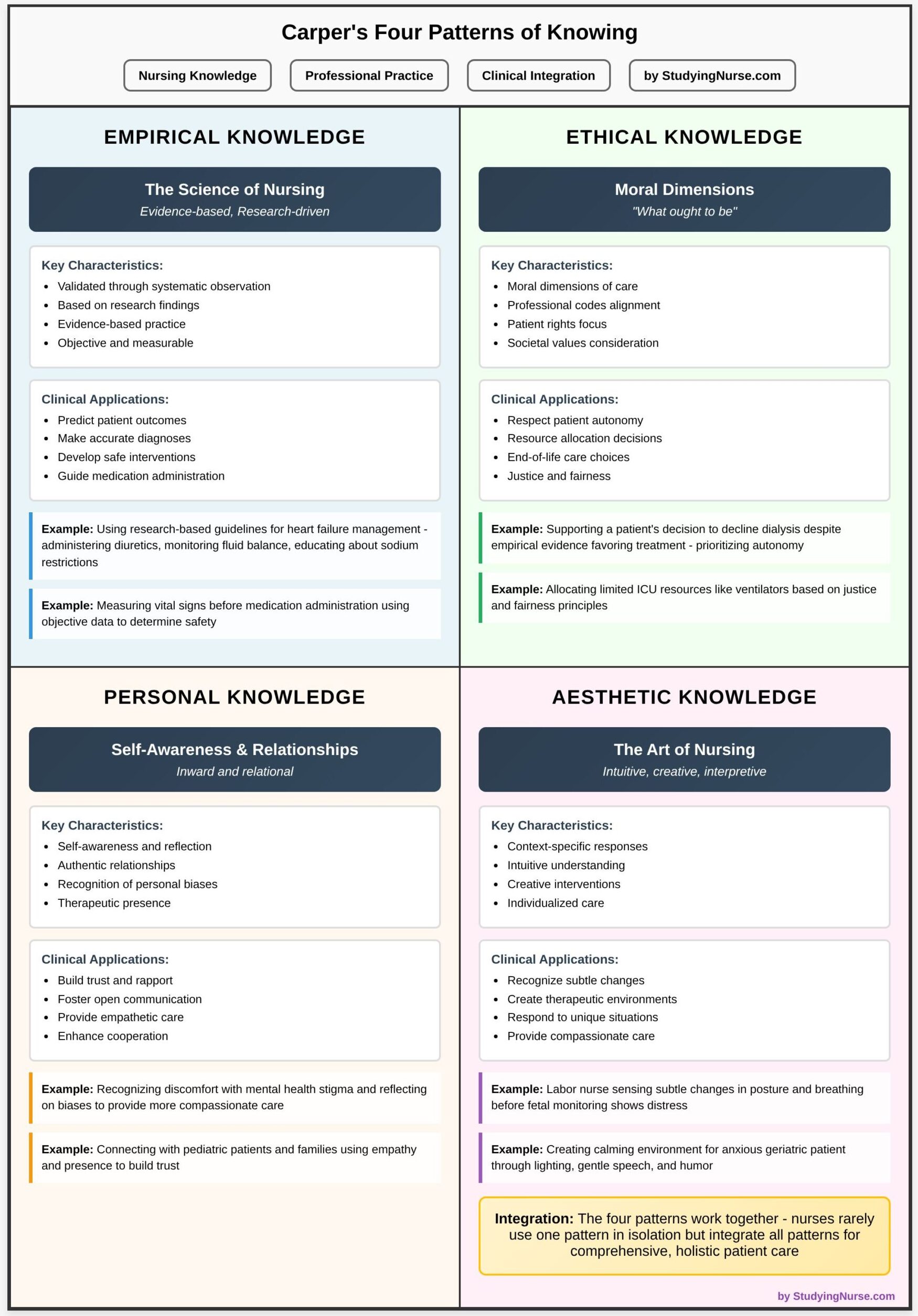

Empirical knowing is the science of nursing, grounded in measurable facts, research, and objective evidence. It allows nurses to explain, predict, and control clinical phenomena through systematic observation and scientific knowledge.

- Example 1: A nurse managing a patient with pneumonia uses chest X-ray results, oxygen saturation levels, and evidence-based guidelines for antibiotic therapy to develop a treatment plan. This reliance on objective, research-based evidence reflects empirical knowledge.

- Example 2: In wound care, applying the latest pressure ulcer prevention protocols—such as repositioning schedules and validated risk assessment tools—demonstrates how empirical knowing shapes patient care.

- Why it matters: For students, empirical knowing reinforces the value of nursing research and evidence-based practice. It ensures care is grounded in proven interventions rather than tradition or habit.

2. Ethical Knowing

Ethical knowing addresses the moral dimensions of practice, helping nurses decide what is right or just in a given clinical situation. It involves applying values such as dignity, fairness, and respect when caring for patients.

- Example 1: A nurse caring for a terminally ill patient may face the decision of whether to continue aggressive treatment or transition to palliative care. While empirical data may suggest treatment options, ethical knowing helps the nurse advocate for the patient’s comfort and wishes.

- Example 2: Respecting confidentiality when a family member demands sensitive information about a patient highlights ethical knowing, as the nurse must balance compassion with professional boundaries.

- Why it matters: Ethical knowledge is essential in a field where nurses frequently face dilemmas involving autonomy, informed consent, and resource allocation. Nursing students need to learn how to combine clinical evidence with moral reasoning to navigate these challenges.

3. Personal Knowing

Personal knowing refers to self-awareness and the authentic engagement of the nurse in relationships with patients. It emphasizes the therapeutic use of self, recognizing one’s values, biases, and emotions, and fostering trust.

- Example 1: A nurse caring for a patient with substance use disorder must confront their own preconceived notions to provide compassionate, nonjudgmental care. Awareness of personal attitudes helps strengthen the nurse–patient relationship.

- Example 2: When a patient expresses fear before surgery, the nurse takes time to sit at the bedside, listen actively, and provide reassurance. This act of genuine presence demonstrates personal knowing.

- Why it matters: For nursing students, personal knowledge encourages reflection and growth. It helps them see nursing not only as a technical profession but also as a relational one, where who they are as individuals affects the quality of care.

4. Aesthetic Knowing

Aesthetic knowing is often described as the art of nursing. It involves perceiving the unique qualities of each clinical situation and responding with creativity, sensitivity, and intuition. Unlike empirical knowledge, which is generalizable, aesthetic knowledge is individualized and context-specific.

- Example 1: A nurse notices subtle body language—such as a patient clenching their fists or avoiding eye contact—and realizes the patient is in pain despite denying it. Responding with an adjusted pain management plan shows aesthetic knowing.

- Example 2: In pediatrics, a nurse eases a child’s anxiety before an IV insertion by turning it into a game and using playful distraction. This creative intervention reflects the art of nursing.

- Why it matters: Nursing students must learn that effective nursing is not formulaic. Clinical guidelines provide structure, but every patient is unique. Aesthetic knowing teaches flexibility, empathy, and the ability to tailor interventions to individual needs.

Why Are These Patterns Important in Nursing Practice?

The importance of Carper’s patterns of knowing lies in how they expand the understanding of nursing knowledge beyond a purely scientific model. Nursing students and practitioners alike benefit from recognizing that each pattern contributes to safe, effective, and compassionate care:

- They promote holistic practice. Patients are not just clinical cases; they are individuals with values, emotions, and lived experiences. By integrating empirical, ethical, personal, and aesthetic knowledge, nurses address not only physical needs but also psychological, social, and moral dimensions of care.

- They enhance clinical judgment. Decision-making in nursing often involves uncertainty. For example, when treating an older adult with multiple comorbidities, evidence-based guidelines (empirical) must be balanced with patient preferences (ethical), relational understanding (personal), and context-specific insights (aesthetic). Using all four patterns helps avoid narrow or one-dimensional solutions.

- They strengthen professional identity. Understanding and applying these patterns allows nursing students to see themselves not just as task performers but as members of a discipline with its own body of knowledge. This contributes to a stronger philosophy of nursing and deepens the profession’s role within healthcare.

- They guide education and reflection. In nursing education, the patterns serve as a structure for reflective journaling, case study analysis, and simulation exercises. By practicing how to apply each type of knowledge, students learn to integrate them during clinical practice.

- They support better patient outcomes. Evidence shows that when nurses incorporate both scientific knowledge and relational, ethical, and aesthetic awareness, patients experience more comprehensive care, greater satisfaction, and improved health outcomes.

How Do the Four Patterns of Knowing Function in Nursing Process?

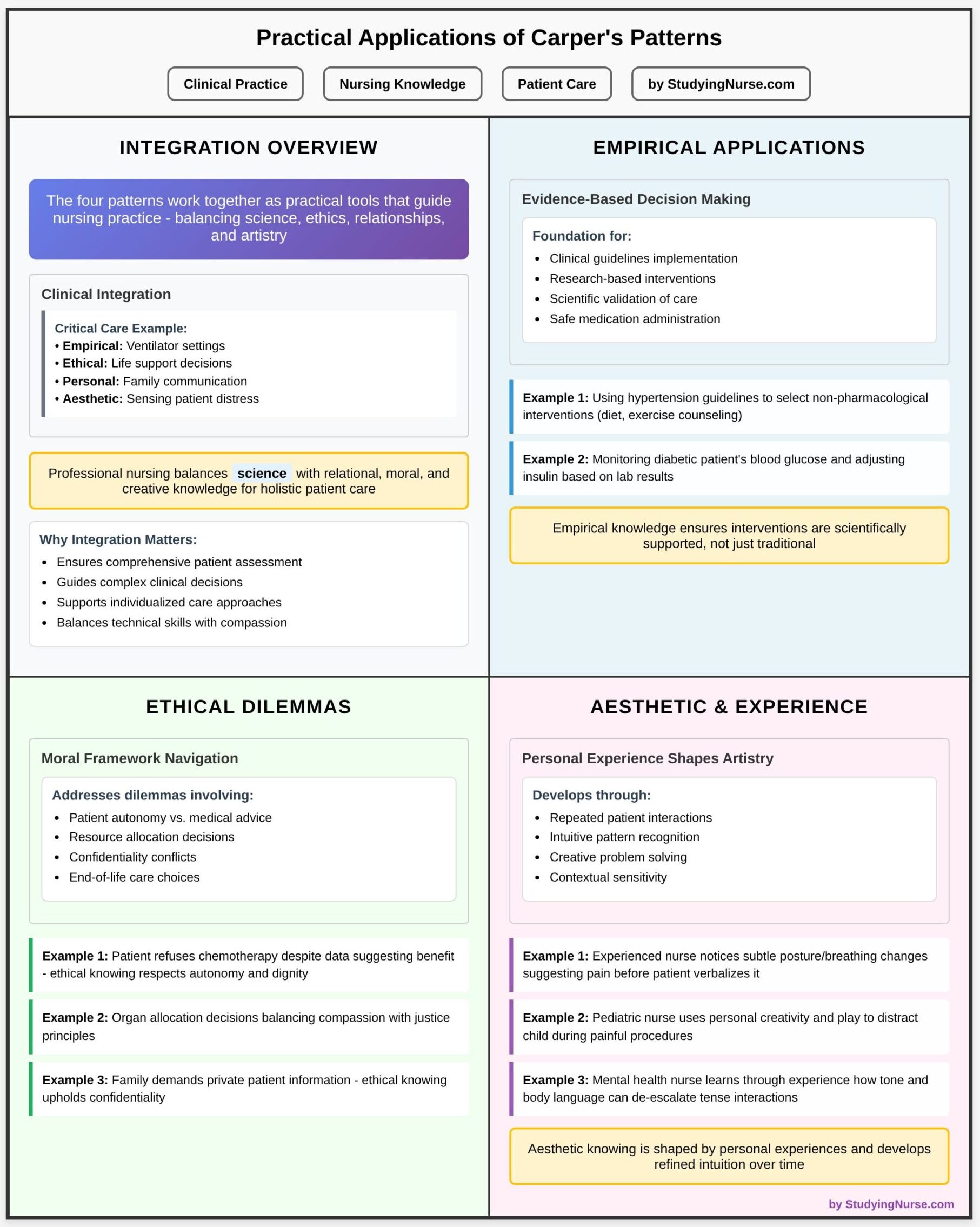

The four fundamental patterns of knowing identified by Carper function as complementary dimensions of nursing knowledge. Each pattern highlights a distinct way of understanding patient needs, but their real value lies in how they work together in daily clinical practice. Nurses rarely rely on one pattern in isolation. Instead, they integrate empirical, ethical, personal, and aesthetic knowing into a seamless response to complex patient situations.

For example, when a nurse cares for a patient recovering from surgery, the decision to administer pain medication draws on empirical knowing (using pain assessment scales), ethical knowing (balancing the risk of opioid dependency with the patient’s right to comfort), personal knowing (listening empathetically to the patient’s fears), and aesthetic knowing (noticing subtle facial cues that the patient is in more distress than they admit). In this way, the patterns of knowing in nursing become practical tools that guide judgment, improve patient care, and strengthen the professional practice of nursing.

What Is Empirical Knowledge, and How Is It Applied in Nursing?

Empirical knowledge is the dimension of nursing that reflects the science of nursing. It is validated through systematic observation, research findings, and evidence-based practice. Nurses use this type of knowledge to predict patient outcomes, make accurate diagnoses, and develop safe interventions.

- Example 1: In treating heart failure, a nurse uses research-based guidelines to administer diuretics, monitor fluid balance, and educate patients about dietary sodium restrictions. This demonstrates how empirical knowledge translates research into practice.

- Example 2: A student nurse measuring vital signs before medication administration relies on objective data—blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate—to decide whether it is safe to give the drug.

Empirical knowing emphasizes nursing science as a discipline built on inquiry and verification. In nursing education, students are trained to critically appraise research articles, apply evidence-based practice, and document findings systematically in the nursing process. Without empirical knowledge, nursing care risks becoming inconsistent, subjective, and unsafe.

What Role Does Ethical Knowledge Play in Patient Care?

Ethical knowledge (or ethical knowing) is concerned with the moral dimensions of care. It guides nurses in making choices that align with professional codes, patient rights, and societal values. While empirical knowledge answers “what is,” ethical knowledge answers “what ought to be.”

- Example 1: A nurse caring for a patient with end-stage renal disease may face the dilemma of whether to encourage dialysis or support the patient’s decision to decline treatment. Empirical evidence may favor continuing dialysis, but ethical knowing prioritizes respecting the patient’s autonomy.

- Example 2: In an intensive care unit, allocating limited resources such as ventilators requires nurses to consider justice and fairness. Here, ethical knowing guides action beyond technical expertise.

For nursing students, understanding ethical knowing is vital because clinical situations are rarely straightforward. The nursing profession emphasizes ethics through codes of conduct and classroom debates on moral dilemmas. By cultivating ethical knowledge, nurses ensure their actions are not only clinically sound but also morally defensible.

How Does Personal Knowledge Enhance the Nurse-Patient Relationship?

Personal knowing emphasizes the nurse’s capacity for self-awareness, reflection, and authentic relationships. Unlike empirical knowledge, which is external and objective, personal knowledge is inward and relational. It helps nurses recognize how their own experiences, values, and beliefs shape patient interactions.

- Example 1: A nurse caring for a patient with a mental health condition notices feelings of discomfort arising from stigma. By reflecting on these biases, the nurse can approach the patient more compassionately, strengthening therapeutic rapport.

- Example 2: During pediatric care, a nurse who takes time to connect with both child and parents demonstrates personal knowing—using empathy and presence to build trust that facilitates cooperation with treatment.

Personal knowing enhances the nurse–patient relationship by fostering respect, trust, and open communication. In professional nursing, this pattern reminds practitioners that effective care is not only about interventions but also about being present, genuine, and self-aware. Nursing students often practice personal knowing through reflective journaling, mentorship, and simulated patient interactions.

In What Ways Does Aesthetic Knowledge Influence Nursing Practice?

Aesthetic knowing—the art of nursing—captures the intuitive, creative, and interpretive dimensions of care. Unlike empirical knowledge, which is generalized, aesthetic knowledge is context-specific, focusing on what makes each clinical situation unique.

- Example 1: A labor and delivery nurse senses a subtle change in a woman’s posture and breathing before fetal monitoring shows distress. Acting on intuition, the nurse alerts the physician, preventing complications.

- Example 2: In geriatric care, a nurse creates a calming environment for an anxious patient by adjusting lighting, speaking gently, and using humor. This creative, relational intervention reflects aesthetic knowing.

Aesthetic knowing underscores that nursing care is not formulaic. While science provides a foundation, the art of nursing ensures that care is individualized, compassionate, and responsive. In nursing education, aesthetic knowing is cultivated through clinical simulations, storytelling, and reflective practice, teaching students to see beyond checklists and guidelines.

Why Is It Important to Integrate All Four Way of Knowing?

The integration of the four fundamental patterns of knowing—empirical, ethical, personal, and aesthetic—is essential for holistic nursing practice. While each form of knowledge offers unique insights, it is their cohesion that ensures nursing care is both scientifically sound and human-centered.

For instance, a nurse caring for a stroke patient cannot rely solely on empirical evidence, such as rehabilitation guidelines. Ethical reflection is required to respect patient autonomy in setting recovery goals, personal knowing builds trust and motivates the patient, and aesthetic knowing helps the nurse adapt exercises creatively to the individual’s needs. Without integration, care risks becoming fragmented—either overly technical, excessively moralistic, or purely relational without evidence to back decisions.

Thus, the patterns of knowing in nursing function not as isolated domains but as interconnected pillars. Their integration highlights nursing as a discipline of knowledge and practice that combines science, morality, self-awareness, and art.

How Can Integrating These Patterns Improve Patient Outcomes?

When nurses apply all four ways of knowing, the impact extends directly to patient outcomes. Research in nursing science shows that combining empirical knowledge with relational, ethical, and aesthetic considerations leads to safer, more effective, and more compassionate care.

- Example 1: In oncology, empirical knowledge guides chemotherapy protocols, while ethical knowing ensures informed consent, personal knowing fosters trust during difficult conversations, and aesthetic knowing helps the nurse find creative ways to comfort patients during treatment. This integration improves adherence, reduces anxiety, and enhances quality of life.

- Example 2: In mental health, using evidence-based interventions (empirical) alongside respect for patient dignity (ethical), therapeutic presence (personal), and creative communication strategies (aesthetic) leads to better engagement and recovery outcomes.

By blending scientific knowledge with empathy and moral reasoning, nurses provide care that patients perceive as both technically competent and deeply caring. For students, this demonstrates why Carper’s ways of knowing remain central to the practice of nursing.

What Are the Challenges in Applying All Four Ways of Knowing in Nursing?

Despite their value, applying all four fundamental patterns of knowing consistently is not without challenges.

- Time constraints in clinical practice: Heavy workloads and documentation demands often push nurses toward prioritizing empirical tasks, such as charting or monitoring lab values, at the expense of relational or reflective dimensions.

- Educational emphasis on science: Nursing curricula often stress empirical knowledge and evidence-based practice, which may overshadow ethical, personal, and aesthetic knowing. Students may struggle to value these equally important forms of knowing.

- Complexity of real-world situations: Ethical dilemmas, such as balancing autonomy with beneficence, can make it difficult to apply theory in practice. Similarly, aesthetic knowing, which relies on intuition, may be undervalued or dismissed as subjective.

- Personal barriers: Nurses who lack self-awareness or reflective skills may find it challenging to practice personal knowing effectively.

- Example: A new nurse in an emergency department may focus on administering medications (empirical) but feel unprepared to comfort grieving families (personal and aesthetic), highlighting the difficulty of balancing all four.

Recognizing these challenges helps nursing students understand that integrating patterns of knowledge is a skill that develops with experience, mentorship, and continued knowledge development in nursing.

How Can Nurses Develop a Balanced Approach to Personal Knowing?

To apply Carper’s framework effectively, nurses need deliberate strategies for balancing the patterns of knowledge in daily practice:

- Reflective practice: Keeping journals, debriefing after clinical shifts, or engaging in guided reflection during nursing education fosters self-awareness and strengthens personal knowing.

- Ethics discussions and case studies: Participation in ethics rounds or classroom debates helps nurses develop confidence in applying ethical knowledge when dilemmas arise.

- Simulation and role-play: High-fidelity simulation allows students to practice integrating empirical skills with relational and aesthetic responses in safe, controlled environments.

- Mentorship and modeling: Learning from experienced nurses who demonstrate integration—such as blending intuition with evidence in complex cases—supports growth in all four domains.

- Continuous learning: Staying current with nursing research ensures empirical knowing is strong, while exposure to literature, philosophy of nursing, and the art of nursing deepens the other dimensions.

- Example: A nursing student in pediatrics may balance empirical knowing (using pain scales), ethical knowing (advocating for appropriate analgesia), personal knowing (comforting the child and parents), and aesthetic knowing (distracting the child with play). With practice, this balanced approach becomes second nature.

Developing this balance ensures that nurses do not privilege one pattern of knowing at the expense of others. Instead, they provide holistic, effective nursing care that addresses the full spectrum of patient needs.

What Are Practical Applications of the Carper Patterns of Knowing in Nursing Knowledge?

The Carper patterns of knowing are not abstract concepts but practical tools that guide the practice of nursing. In daily clinical situations, nurses integrate empirical, ethical, personal, and aesthetic knowing to ensure that care is effective, compassionate, and individualized.

- Example: In critical care, empirical knowing shapes the use of ventilator settings, ethical knowing guides decisions about life support, personal knowing helps the nurse communicate with anxious families, and aesthetic knowing allows the nurse to sense subtle patient distress before monitors confirm it.

For nursing students, recognizing these practical applications demonstrates that professional nursing is more than task completion. It is a discipline that balances the science of nursing with relational, moral, and creative knowledge to support holistic patient care.

How Can Nurses Use Empirical Knowledge to Inform Clinical Decisions?

Empirical knowledge provides the foundation for evidence-based decision-making. It is validated through nursing research, clinical trials, and systematic observation. By applying empirical knowing, nurses ensure that interventions are not only traditional but scientifically supported.

- Example 1: When a nurse uses current hypertension guidelines to select appropriate non-pharmacological interventions (such as dietary changes or exercise counseling), they are applying empirical knowing.

- Example 2: Monitoring a diabetic patient’s blood glucose and adjusting insulin based on lab results reflects the empirical knowledge necessary for safe nursing interventions.

What Ethical Dilemmas Can Be Addressed Through Ethical Knowledge?

Nurses frequently encounter dilemmas where no single correct answer exists. Here, ethical knowledge—sometimes called ethical knowing—provides a framework to navigate decisions grounded in values such as justice, autonomy, and beneficence.

- Example 1: A patient with advanced cancer chooses to refuse further chemotherapy. While empirical data may suggest continued treatment could extend life, ethical knowing respects the patient’s autonomy and dignity.

- Example 2: During organ allocation, nurses face the ethical challenge of fairness when deciding which patient receives a scarce resource. Ethical knowledge helps balance compassion with justice.

- Example 3: Confidentiality dilemmas arise when family members demand information a patient wishes to keep private. Here, ethical knowing ensures that fundamental values of the nursing profession are upheld.

How Can Personal Experiences Shape a Nurse’s Aesthetic Knowledge?

Aesthetic knowing—the art of nursing—relies heavily on intuition, creativity, and perception. Unlike empirical knowledge, which is generalizable, aesthetic knowing is shaped by personal experiences and sensitivity to unique patient contexts.

- Example 1: A nurse who has cared for multiple post-operative patients may notice subtle changes in a patient’s posture or breathing that suggest pain long before the patient verbalizes it. This refined intuition develops from experience.

- Example 2: A pediatric nurse draws on personal experiences of play and creativity to distract a child during a painful procedure, transforming fear into calm cooperation.

- Example 3: In mental health, a nurse learns through experience how tone of voice or body language can de-escalate a tense interaction, applying aesthetic knowledge to create safety and trust.

Struggling to connect Carper’s patterns to practice?

Our experts can craft a polished assignment.

Conclusion

Barbara Carper’s framework of the fundamental patterns of knowing remains one of the most influential contributions to the development of nursing knowledge and professional identity. By outlining four distinct yet interrelated dimensions—empirical knowing, ethical knowing, personal knowing, and aesthetic knowing—Carper provided nurses with a model that integrates the science of nursing with the art of nursing, ensuring that care extends beyond clinical tasks to address the full complexity of human experience.

In nursing practice, these patterns of knowledge function as complementary lenses. Empirical knowledge guides evidence-based assessments and interventions, while ethical knowledge ensures decisions are grounded in moral responsibility and respect for patient autonomy. Personal knowing builds authentic relationships that foster trust and compassion, and aesthetic knowing allows nurses to respond creatively and intuitively to the uniqueness of each clinical situation. When these ways of knowing in nursing are applied in cohesion, they strengthen the quality of patient care and elevate the nursing profession.

For nursing students, understanding Carper’s ways of knowing is not just an academic exercise but a foundation for professional growth. Nurses apply patterns of knowing in daily practice—whether in acute care, community health, or advanced clinical practice—to navigate the challenges of modern healthcare. Yet, applying all four patterns consistently is not without obstacles. Balancing competing demands, ethical dilemmas, and diverse patient needs requires reflection, mentorship, and continuous knowledge development in nursing.

Looking ahead, integrating Carper’s model into nursing education, nursing research, and policy discussions will remain critical. As healthcare evolves, the ability of nurses to blend scientific knowledge with humanistic and ethical understanding will define effective and compassionate care. Ultimately, Carper’s framework reminds us that nursing as a practice is more than procedures and protocols—it is a discipline rooted in knowing and knowledge, shaped by inquiry, morality, self-awareness, and artistry. By embracing these patterns as a unified whole, nurses can continue to advance their profession and contribute meaningfully to the health and well-being of individuals, families, and communities.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are Carper’s patterns of knowing in nursing?

Carper identified four patterns of knowing in nursing: empirical knowing (science of nursing), ethical knowing (moral responsibility), personal knowing (self-awareness and authentic relationships), and aesthetic knowing (art of nursing and intuitive practice).

What are the 5 types of knowledge in nursing?

In addition to Carper’s original four, scholars later added a fifth: emancipatory knowing, which focuses on social justice, equity, and addressing healthcare disparities.

What are the four ways of knowing in nursing theory?

The four ways of knowing, according to Carper, are empirical, ethical, personal, and aesthetic—together providing a holistic framework for nursing knowledge and practice.

What are the ways of knowing as a nurse?

As a nurse, ways of knowing include applying scientific evidence (empirical), upholding ethics in patient care, building trust through personal knowing, practicing the art of nursing with aesthetic insight, and, in modern frameworks, incorporating emancipatory knowledge to advocate for fairness in healthcare.