Addison Disease vs Cushing Syndrome: Understanding Adrenal Gland Disorders

Adrenal disorders present some of the most striking contrasts in endocrine practice, and understanding them is essential for safe, effective nursing care. Addison’s disease vs Cushing’s syndrome represents two ends of the adrenal function spectrum: one characterized by insufficient hormone production and the other by chronic hormone excess affecting multiple organ systems. Both conditions originate in the adrenal gland, a small but critical structure perched above the kidneys that produces vital regulators of metabolism and homeostasis. In Addison’s disease, disruption of normal hormone synthesis leads to adrenal insufficiency, whereas in Cushing’s syndrome there is prolonged exposure to high levels of cortisol, whether from internal overproduction or external sources such as medications. These opposing pathophysiologies manifest in distinct signs and symptoms that influence patient assessment, diagnostics, and management strategies in clinical settings.

Nursing professionals must be familiar with the mechanisms underlying these conditions to differentiate clinical presentations accurately and initiate appropriate interventions. Addison’s disease often involves autoimmune damage to the adrenal cortex, leading to inadequate secretion of both glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids, whereas Cushing’s syndrome reflects chronic cortisol excess with widespread metabolic effects. These variations not only affect vital functions like blood pressure regulation and immune response but also determine the trajectory of diagnostic evaluation and long‑term care planning for patients.

This guide explores core physiological concepts, clinical features, diagnostic approaches, and evidence‑based nursing considerations for both disorders. By grounding practice in a thorough understanding of these contrasting adrenal pathologies, nurses can enhance clinical judgment, improve patient outcomes, and contribute meaningfully to interdisciplinary care for individuals affected by these complex endocrine conditions.

Key Differences Between Addison’s Disease and Cushing’s Syndrome

Overview of Adrenal Gland Function

The adrenal gland is a small, triangular endocrine organ located above each kidney that plays a critical role in maintaining homeostasis. Its dual structure—the cortex and medulla—allows it to produce a wide range of hormones essential for metabolism, electrolyte balance, cardiovascular stability, and stress adaptation.

- Adrenal Cortex: Divided into three layers, each producing specific steroid hormones:

- Zona glomerulosa: Produces aldosterone, which regulates sodium and potassium balance and maintains intravascular volume.

- Zona fasciculata: Produces cortisol, a glucocorticoid that affects glucose metabolism, immune modulation, and stress response.

- Zona reticularis: Produces adrenal androgens that contribute to secondary sexual characteristics.

- Adrenal Medulla: Produces catecholamines (epinephrine and norepinephrine) that mediate acute stress responses.

In Addison’s disease vs Cushing’s syndrome, the adrenal cortex is central to pathophysiology:

- Addison’s disease is characterized by adrenal insufficiency, often caused by autoimmune destruction of the cortex, which leads to inadequate production of cortisol and sometimes aldosterone.

- Cushing’s syndrome is defined by excess cortisol, which may result from pituitary overproduction of ACTH (Cushing disease), adrenal tumors, ectopic ACTH secretion, or prolonged use of corticosteroids.

Cortisol Patterns in Disease vs Syndrome

Cortisol secretion normally follows a circadian rhythm, peaking in the early morning to provide energy and declining in the evening. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis regulates this rhythm:

- The hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH).

- CRH stimulates the pituitary gland to secrete adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH).

- ACTH triggers cortisol production in the adrenal cortex.

- Negative feedback by cortisol maintains homeostasis.

Disruptions in cortisol patterns explain clinical differences between the two disorders:

- Addison’s disease:

- Chronic lack of cortisol leads to persistent low cortisol levels, eliminating the normal morning peak.

- Reduced cortisol impairs metabolism, stress response, and cardiovascular function.

- Elevated ACTH levels (due to feedback) result in hyperpigmentation of skin and mucous membranes.

- Electrolyte disturbances, such as hyponatremia and hyperkalemia, arise due to aldosterone deficiency.

- Patients may present with fatigue, weight loss, dizziness, and hypotension, particularly during stress.

- Cushing’s syndrome:

- Characterized by excess cortisol, which often flattens or reverses the normal diurnal rhythm.

- Elevated evening cortisol can disrupt sleep and exacerbate hyperglycemia.

- Sustained cortisol excess causes protein catabolism (muscle wasting), central fat deposition, and immunosuppression.

- Patients often present with truncal obesity, moon face, buffalo hump, thin skin, and delayed wound healing.

- Hypertension and glucose intolerance are common due to cortisol-mediated sodium retention and insulin resistance.

Clinical example: A patient with Addison’s disease may collapse during minor surgery due to inadequate stress response, whereas a patient with Cushing’s syndrome may develop infections postoperatively because of cortisol-induced immunosuppression. These contrasts demonstrate why nurses must understand cortisol dynamics in both disorders.

Causes of Adrenal Disorders

The mechanisms leading to Addison’s disease and Cushing’s syndrome differ in origin and clinical impact:

Addison’s Disease Causes:

- Autoimmune destruction of the adrenal cortex: Most common in developed countries. Autoantibodies target enzymes involved in steroid synthesis, leading to primary adrenal insufficiency.

- Infections: Tuberculosis, HIV, or fungal infections can destroy adrenal tissue.

- Adrenal hemorrhage or infarction: Often associated with sepsis, trauma, or anticoagulation.

- Secondary adrenal insufficiency: Chronic corticosteroid use suppresses ACTH production by the pituitary, reducing adrenal cortisol output. In these cases, aldosterone secretion is usually preserved.

Cushing’s Syndrome Causes:

- Cushing disease: A benign pituitary tumor secretes excessive ACTH, stimulating the adrenal cortex to overproduce cortisol.

- Adrenal tumors: Autonomous cortisol production independent of ACTH feedback.

- Ectopic ACTH secretion: Rare tumors outside the pituitary produce ACTH, often from small-cell lung carcinoma.

- Exogenous corticosteroid therapy: Chronic high-dose administration mimics hypercortisolism, suppressing endogenous ACTH.

Nursing implications:

- Identification of the common cause is critical for treatment planning.

- Differentiating primary adrenal vs secondary pituitary or exogenous causes informs both diagnostic testing and education.

- Nurses play a central role in monitoring for complications such as hypotension in Addison’s disease and hyperglycemia in Cushing’s syndrome.

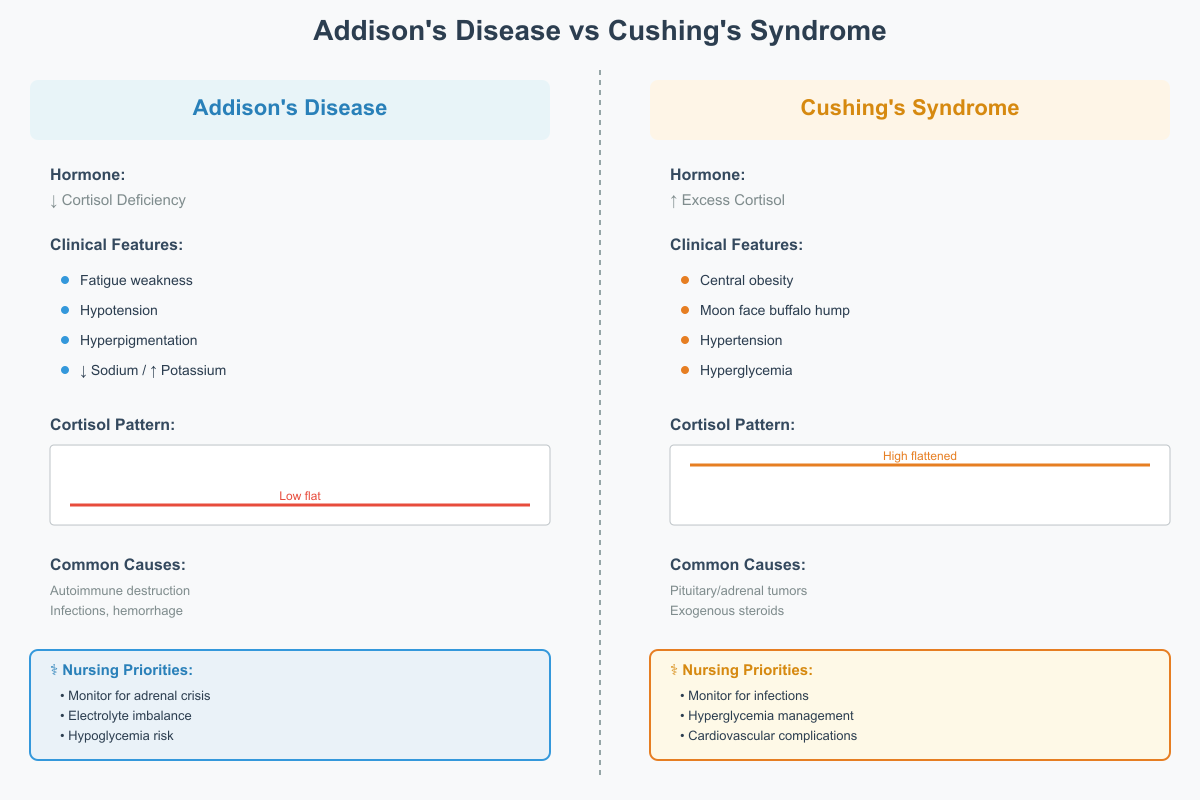

Summary of Key Differences

| Feature | Addison’s Disease | Cushing’s Syndrome |

|---|---|---|

| Hormone production | Cortisol deficiency | Excess cortisol |

| Etiology | Autoimmune destruction, infections, hemorrhage | Pituitary tumor, adrenal tumor, ectopic ACTH, exogenous steroids |

| Clinical features | Fatigue, hypotension, hyperpigmentation, hyponatremia, hyperkalemia | Central obesity, moon face, buffalo hump, hypertension, hyperglycemia, immunosuppression |

| Cortisol rhythm | Low throughout the day, no morning peak | High and flattened diurnal rhythm |

| Nursing priorities | Monitor for adrenal crisis, electrolyte imbalance, hypoglycemia | Monitor for infection, hyperglycemia, cardiovascular complications |

Clinical scenario: A patient with Addison’s disease may present with dizziness and salt cravings during heat exposure due to hypotension and low aldosterone, whereas a patient with Cushing’s syndrome may experience recurrent infections and fragile skin from cortisol excess. Nurses must tailor assessment, monitoring, and education based on these pathophysiological contrasts.

Recognizing Symptoms and Causes of Adrenal Disorders

Clinical Manifestations of Addison’s Disease

Addison’s disease is a primary form of adrenal insufficiency caused by loss of functional adrenal cortical tissue. This leads to inadequate secretion of essential hormones, producing a constellation of symptoms and causes that reflect disruption of metabolic, cardiovascular, and fluid‑electrolyte homeostasis.

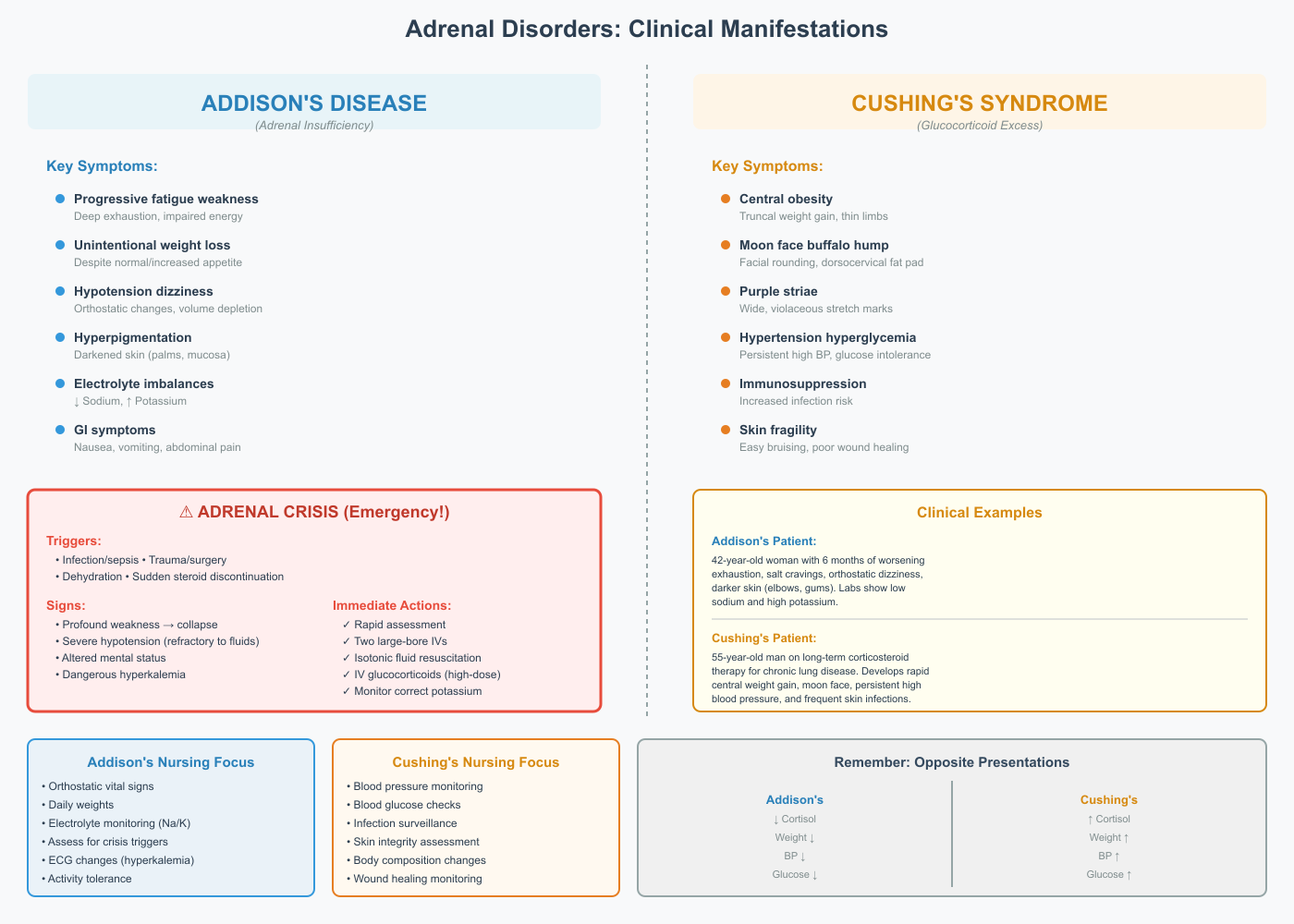

The hallmark clinical features include:

1. Progressive Fatigue and Weakness

Patients often describe a deep sense of exhaustion that does not improve with rest. This fatigue stems from reduced glucocorticoid hormone availability, leading to impaired glucose mobilization and decreased energy production. Nursing assessment should explore activity tolerance, ability to perform daily tasks, and signs of functional decline.

2. Unintentional Weight Loss

Weight loss occurs even with normal or increased appetite, reflecting a catabolic state as tissues fail to mount appropriate metabolic responses. Careful tracking of daily weights and dietary intake assists nurses in early recognition.

3. Hypotension and Orthostatic Changes

Loss of mineralocorticoid activity results in sodium loss and intravascular volume depletion. Patients complain of dizziness upon standing and may have measurable drops in blood pressure. Orthostatic vital signs should be assessed routinely in suspected cases.

4. Hyperpigmentation of Skin and Mucosa

Hyperpigmentation results from elevated pro‑opiomelanocortin fragments due to chronic stimulation of the pituitary. This characteristic darkening of skin, especially in palmar creases and buccal mucosa, is a key diagnostic clue.

5. Electrolyte Disturbances – High Potassium and Hyponatremia

Mineralocorticoid deficiency causes urinary loss of sodium and retention of potassium. Laboratory findings typically include:

- High potassium levels

- Low serum sodium

These changes increase risk for arrhythmias, cramps, and profound weakness. Nurses must monitor electrolyte panels, ECG changes, and signs of hyperkalemia.

6. Gastrointestinal Symptoms

Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea are common. These symptoms can be nonspecific but, in context with hypotension and electrolyte imbalance, raise suspicion for adrenal dysfunction.

Clinical Example: A 42‑year‑old woman reports six months of worsening exhaustion, craving salty foods, lightheadedness when standing, and darker skin around her elbows and gums. Laboratory studies reveal hyponatremia and hyperkalemia. This presentation, especially with progressive weakness and skin changes, should prompt urgent evaluation for Addison’s disease.

Clinical Manifestations of Cushing’s Syndrome

In contrast, Cushing’s syndrome is a condition of chronic glucocorticoid excess due to autonomous overproduction or prolonged therapeutic steroid use. The pattern of manifestations differs significantly from adrenal insufficiency and reflects sustained metabolic, cardiovascular, and immune alteration.

Key clinical features include:

1. Central Weight Gain with Peripheral Muscle Wasting

A characteristic redistribution of body fat produces truncal obesity with thin extremities, reflecting protein catabolism and altered glucose handling. Nurses should evaluate changes in body habitus over time.

2. “Moon Face” and “Buffalo Hump”

Facial rounding and a dorsocervical fat pad give a distinctive appearance. These changes are visible physical markers that support clinical suspicion.

3. Purple Striae on Abdomen and Thighs

These wide, violaceous stretch marks appear due to rapid tissue expansion and dermal thinning. They differ from typical striae seen with rapid weight changes and are considered highly suggestive of hypersecretion states.

4. High Blood Pressure and Glucose Intolerance

Excess glucocorticoid hormone activity promotes sodium retention and vascular sensitivity to catecholamines. Hypertension is often persistent and difficult to control. Concurrently, increased hepatic glucose output and insulin resistance may lead to hyperglycemia or new‑onset diabetes. Nurses should monitor blood pressure and glucose patterns closely, especially in patients on prolonged steroid therapy.

5. Immunosuppression and Increased Infection Risk

Glucocorticoid excess suppresses cellular immunity, reducing the inflammatory response. Patients may have frequent infections with atypical presentations. Vigilant assessment for subtle signs of infection is crucial.

6. Skin Fragility and Poor Wound Healing

Protein catabolism weakens dermal structures, so minor trauma may lead to bruising or slow‑healing ulcers. This has significant implications for wound care and preventative skin assessments in hospitalized patients.

Clinical Example: A 55‑year‑old man receiving long‑term corticosteroid therapy for chronic lung disease develops rapid central weight gain, rounding of the face, persistent high blood pressure, and frequent skin infections. These signs should prompt evaluation for Cushing’s syndrome.

Adrenal Crisis in Addison’s Disease

An adrenal crisis is a life‑threatening acute decompensation precipitated by physiologic stress in a patient with underlying adrenal failure. It represents an endocrine emergency requiring rapid recognition and intervention.

Common Triggers:

- Acute infection or sepsis

- Trauma or surgery

- Severe dehydration

- Sudden discontinuation of exogenous steroids

Key Features of Adrenal Crisis:

- Profound weakness progressing to collapse

- Severe hypotension refractory to fluid resuscitation

- Confusion or altered mental status

- Significant electrolyte imbalance with dangerously high potassium

Immediate Nursing Actions:

- Rapid assessment: Recognize the combination of hypotension, dehydration, and history of adrenal dysfunction

- Intravenous access: Establish two large‑bore IV lines

- Fluid resuscitation: Administer isotonic fluids promptly

- IV hormone replacement: Administer high‑dose intravenous glucocorticoids per protocol

- Electrolyte correction: Monitor and correct potassium to prevent arrhythmias

Example Scenario: A patient with known adrenal insufficiency presents with fever, vomiting, and dizziness after a gastrointestinal infection. Blood pressure is dangerously low and potassium elevated. Immediate institution of emergency protocols, including IV fluids and steroids, is critical to prevent cardiovascular collapse and death.

Diagnostic Evaluation of Adrenal Gland Disorders

Laboratory Assessments

Accurate diagnosis of disorders involving adrenal hormone imbalance begins with targeted laboratory assessments that clarify whether the clinical presentation reflects inadequate hormone production or excessive exposure. In patients suspected of adrenal dysfunction, a structured panel of tests helps confirm the diagnosis, differentiate between causes, and guide treatment.

One cornerstone of endocrine testing is measurement of hormone output under basal and stimulated conditions. For example, baseline serum hormone concentrations provide initial insight into physiological status, while dynamic testing can reveal how well the glands respond to regulatory signals. In suspected adrenal insufficiency, early morning blood samples are often obtained because hormone secretion normally exhibits a diurnal peak at this time, maximizing the chance of detecting abnormally low values.

A commonly used parameter is urinary free cortisol, which reflects the total amount of unconjugated hormone excreted over a 24‑hour period. Elevated urinary free cortisol can signify excessive production, whereas persistently low urinary excretion supports a diagnosis of deficiency. Nurses play a key role in ensuring that patients understand the proper collection technique for 24‑hour urine specimens, as errors in collection can lead to misleading results.

In addition to hormone measurements, electrolyte panels are essential. Disturbances in sodium and potassium can be both a cause and a consequence of adrenal pathology. For instance, low sodium and high potassium are characteristic of impaired mineralocorticoid activity and must be interpreted in the context of the clinical picture. Frequent monitoring of these values allows nurses to anticipate complications such as cardiac arrhythmias or neuromuscular irritability, and to communicate urgent findings to the medical team.

Imaging Studies

While laboratory tests assess biochemical function, imaging studies evaluate anatomical structures that may contribute to endocrine disorder. Radiologic visualization of the adrenal glands and adjacent endocrine organs is a critical step when biochemical tests suggest abnormal hormone production.

Ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are commonly used to identify structural abnormalities such as nodules, enlargement, or atrophy. For example, an adrenal mass visualized on CT in a patient with biochemical evidence of excessive hormone output raises concern for an adrenal tumor, which may produce hormones autonomously.

Imaging also plays a central role in distinguishing between primary gland pathology and central regulatory disorders. In patients with suspected central overproduction, scans of the brain focus on the region housing the gland responsible for regulatory signals. Detection of a pituitary lesion in this region can explain excessive hormonal stimulation of the peripheral glands. Conversely, when no central abnormality is identified, clinicians may pursue other sources, such as ectopic production from non‑endocrine tumors.

From a nursing perspective, understanding the rationale for imaging supports appropriate patient preparation and education. For instance, explaining the need for contrast agents, ensuring that patients have completed necessary safety screening (e.g., for renal function or metal implants), and assessing for claustrophobia all contribute to a successful and clinically meaningful imaging session.

Stimulation and Suppression Tests

Dynamic endocrine testing extends beyond baseline measurements to assess physiologic responsiveness of the glands and their regulatory networks. Two important categories are stimulation tests and suppression tests, which help clinicians differentiate among types of dysfunction.

A stimulation test evaluates the capability of a gland to respond to a known stimulus. For example, after intravenous administration of a stimulating agent, hormone levels are measured at defined intervals. In individuals with impaired adrenal hormone production, the expected rise in hormone output may be absent or blunted, indicating a primary inability of the gland to respond to stimulation. This helps confirm a diagnosis of inadequate gland responsiveness rather than secondary regulatory failure.

Suppression tests take the opposite approach: by administering a substance that normally reduces hormone secretion, clinicians observe whether the expected decline occurs. In those with excessive endogenous hormone production, such as when the regulatory feedback systems fail, suppression may be attenuated or absent. These tests are particularly useful when imaging and initial laboratory findings suggest autonomous hormone secretion.

Interpreting the results of dynamic tests requires careful attention to timing, dosing, and clinical context. Nurses involved in these procedures ensure correct timing of specimen collection, monitor for adverse reactions to the agents administered, and provide clear instructions for patients undergoing outpatient testing. Accurate results depend on strict adherence to protocol, making nursing vigilance essential.

Putting It Together: A Clinical Example

Consider a patient presenting with fatigue, dizziness upon standing, and unintentional weight loss. Laboratory assessments reveal low baseline serum hormone values with high potassium and low sodium, suggesting impaired hormone production. A stimulation test fails to elicit an appropriate rise in hormone output, supporting a diagnosis of inadequate gland responsiveness. Subsequent imaging shows atrophy of the hormone‑producing cortex. This sequence of diagnostic steps not only confirms the presence of a functional deficit but also guides treatment planning, including hormone replacement strategies and electrolyte management.

In contrast, a patient with central weight gain, persistent high blood pressure, and easy bruising may have elevated urinary free cortisol. Suppression testing fails to decrease hormone output, and imaging reveals a mass in the region controlling regulatory signals. These findings point toward autonomous hormonal overproduction, which may benefit from targeted surgical or medical intervention.

Treatment and Management Strategies for Adrenal Disorders

Hormone Replacement in Addison’s Disease

Addison’s disease represents a state of adrenal insufficiency, requiring prompt and lifelong hormone replacement therapy to restore physiologic homeostasis. The primary goal is to mimic normal hormone production and prevent complications such as adrenal crisis.

Glucocorticoid Replacement:

- Hydrocortisone is the mainstay therapy because it closely resembles endogenous cortisol. Typical dosing involves divided doses, with a larger proportion administered in the morning to mimic natural circadian rhythm and a smaller dose in the afternoon.

- Nurses must monitor clinical response, observing for improved energy, normalized blood pressure, and resolution of fatigue.

- Patients should be educated about the importance of adherence to the dosing schedule and recognizing signs of under- or over-replacement, including hypotension, lethargy, or weight gain.

Mineralocorticoid Replacement:

- In primary adrenal insufficiency, aldosterone deficiency leads to hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, and hypotension.

- Fludrocortisone is used to restore sodium balance and maintain blood pressure.

- Electrolytes must be closely monitored, and nurses should teach patients to report dizziness, palpitations, or unusual fatigue, which may indicate imbalances.

Practical Nursing Example: A 35-year-old patient newly diagnosed with Addison’s disease presents with hypotension, fatigue, and hyponatremia. Initiation of hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone therapy, combined with daily monitoring of blood pressure and serum electrolytes, results in stabilized vital signs and improved energy within one week. Patient education includes stress dosing for illness and instructions to wear a medical alert bracelet.

Management of Cushing’s Syndrome

Management of Cushing’s syndrome depends on the underlying cause of excess cortisol and aims to normalize hormone levels while minimizing complications.

Surgical Options:

- Adrenalectomy may be indicated for unilateral adrenal tumors producing excess cortisol.

- Pituitary tumor removal is the treatment of choice for Cushing disease, targeting excessive ACTH production.

- Postoperative monitoring is critical for adrenal insufficiency, as abrupt removal of the source of cortisol can precipitate a deficiency state.

Medical Management:

- For patients who are not surgical candidates, cortisol synthesis inhibitors (e.g., ketoconazole, metyrapone) reduce hormone production.

- Nursing responsibilities include monitoring cortisol levels, liver function, blood pressure, and glucose, as these medications can have systemic effects.

Practical Nursing Example: A 50-year-old patient with Cushing’s syndrome secondary to a pituitary adenoma undergoes transsphenoidal surgery. Nurses monitor for postoperative hypotension, electrolyte changes, and signs of adrenal insufficiency, adjusting glucocorticoid supplementation as needed to prevent complications.

Acute and Long-Term Nursing Considerations

Effective management of adrenal disorders requires a combination of ongoing monitoring, patient education, and emergency preparedness.

Monitoring Parameters:

- Cortisol levels: Regular assessments help adjust replacement therapy or detect recurrence of hypercortisolism.

- Electrolytes: Sodium and potassium must be checked frequently in Addison’s disease to prevent arrhythmias and neuromuscular complications.

- Blood pressure: Both hypo- and hypertension may indicate inadequate hormone control.

Patient Education:

- Steroid Tapering and Stress Dosing: Patients with Addison’s disease should learn how to increase glucocorticoid doses during illness or surgery to prevent adrenal crisis.

- Infection Risk: Patients with Cushing’s syndrome are immunocompromised and require education on early recognition of infection and hygiene measures.

- Emergency Protocols: Training on self-administration of emergency hydrocortisone injections and recognition of adrenal crisis symptoms is essential for high-risk patients.

Long-Term Care:

- Regular follow-up visits to evaluate hormone replacement efficacy, monitor for complications (osteoporosis, metabolic syndrome), and adjust medications.

- Encouraging lifestyle measures to manage blood pressure, weight, and glycemic control in Cushing’s syndrome.

Clinical Example: A patient with Addison’s disease recovering from a gastrointestinal infection is instructed to increase hydrocortisone dosing temporarily and maintain oral hydration. Nurses provide education on signs of adrenal crisis, including severe hypotension, vomiting, and confusion, and ensure the patient understands when to seek immediate care.

Practical Nursing Applications in Adrenal Disorders

Recognizing High-Risk Patients

Effective nursing care begins with the ability to identify patients at high risk for complications related to adrenal disorders. Early recognition allows timely interventions, prevents acute crises, and improves long-term outcomes.

High-risk groups include:

- Patients with known primary adrenal insufficiency, particularly those with a history of autoimmune destruction of the adrenal cortex.

- Individuals undergoing chronic corticosteroid therapy who may develop secondary adrenal insufficiency upon abrupt discontinuation.

- Patients with pituitary or adrenal tumors that could cause Cushing’s syndrome or Cushing disease.

- Individuals with unexplained electrolyte disturbances (e.g., hyponatremia, hyperkalemia), hypotension, or metabolic imbalances.

Key nursing strategies for identification:

- Systematic assessment of symptoms and causes: Nurses must evaluate complaints such as fatigue, dizziness, weight changes, skin changes, hypertension, or glucose intolerance in a structured manner. For example, unexplained hyperpigmentation combined with low blood pressure may indicate Addison’s disease, whereas central obesity, facial rounding, and persistent high blood pressure suggest Cushing’s syndrome.

- Differentiating primary versus secondary causes:

- Primary adrenal insufficiency results from intrinsic adrenal dysfunction, often accompanied by electrolyte disturbances.

- Secondary insufficiency stems from pituitary or hypothalamic dysfunction, where mineralocorticoid levels may remain normal.

- Monitoring high-risk patients during stressors: Infections, surgery, or trauma can precipitate adrenal crisis in patients with insufficiency. Nurses should ensure prophylactic stress dosing of glucocorticoids and close hemodynamic monitoring during these periods.

Clinical Example: A patient with a history of long-term prednisone use presents with fatigue, hypotension, and salt craving after discontinuing the medication abruptly. Recognizing these symptoms and causes, the nurse immediately alerts the physician, initiates fluid resuscitation, and ensures emergency glucocorticoid replacement, preventing progression to adrenal crisis.

Integrating Knowledge into Patient Care

Applying a deep understanding of adrenal physiology, pathophysiology, and clinical manifestations allows nurses to individualize care plans for patients with adrenal disorders. Effective integration involves assessment, monitoring, patient education, and collaboration with the interdisciplinary team.

1. Individualized Care Planning:

- Tailor hormone replacement therapy schedules to optimize energy levels and circadian patterns. For Addison’s disease, hydrocortisone doses are adjusted based on symptom control, cortisol level monitoring, and electrolyte balance.

- In patients with Cushing’s syndrome, post-surgical monitoring for adrenal insufficiency or ongoing hypercortisolism guides adjustments to therapy and supports recovery.

2. Monitoring for Complications:

- Continuous surveillance of blood pressure, glucose, electrolyte levels, and weight allows early detection of adverse effects.

- Nurses must recognize early signs of adrenal crisis, infection, or metabolic derangements, especially in vulnerable populations such as the elderly or those with multiple comorbidities.

3. Patient Education:

- Teach patients to recognize early warning signs of hormone imbalance, including fatigue, dizziness, hyperpigmentation, or easy bruising.

- Emphasize the importance of adherence to hormone replacement therapy, stress dosing during illness, and gradual tapering when indicated.

- Educate on lifestyle modifications to manage hypertension, glucose intolerance, or obesity in Cushing’s syndrome, supporting holistic health outcomes.

4. Long-Term Support and Follow-Up:

- Encourage regular endocrinology follow-up to adjust therapy based on clinical response and laboratory values.

- Reinforce the need for emergency preparedness, such as carrying medical alert identification and understanding emergency injection protocols.

- Facilitate interdisciplinary communication among physicians, dietitians, and mental health professionals to address complications like osteoporosis, immunosuppression, or psychological distress from chronic disease.

Clinical Example: A 45-year-old patient recovering from adrenalectomy for a cortisol-producing tumor requires careful blood pressure and glucose monitoring. The nurse educates the patient about medication adherence, stress dosing, and recognizing signs of adrenal insufficiency. Follow-up appointments are scheduled to monitor cortisol levels, preventing complications and supporting long-term endocrine stability.

Conclusion

Understanding Addison’s disease vs Cushing’s syndrome is fundamental for nurses managing patients with adrenal gland disorders, as these conditions represent opposite extremes of cortisol imbalance with profound systemic effects. Addison’s disease reflects a state of adrenal insufficiency, characterized by hormone deficiency, hypotension, fatigue, electrolyte disturbances, and risk for life-threatening adrenal crisis. In contrast, Cushing’s syndrome and Cushing disease arise from chronic excess cortisol, producing metabolic, cardiovascular, and immunologic complications such as hypertension, hyperglycemia, obesity, and increased susceptibility to infection. Recognizing the key differences in clinical presentation, hormone regulation, and underlying pathology is essential for accurate assessment, timely diagnosis, and effective intervention.

Nurses play a pivotal role in the management of these disorders, from early recognition of symptoms and causes, through interpretation of diagnostic tests including cortisol levels, ACTH stimulation tests, and imaging, to the implementation of treatment options such as hormone replacement or surgical interventions. Beyond acute care, ongoing monitoring of electrolyte balance, blood pressure, and hormone levels, along with patient education regarding stress dosing, steroid tapering, and emergency preparedness, is critical to prevent complications and ensure long-term stability.

By integrating pathophysiologic knowledge with clinical vigilance, nurses can anticipate complications, individualize care, and support patients in navigating the complexities of adrenal disorders. Ultimately, mastery of these concepts not only enhances clinical competence but also improves patient outcomes, reduces the risk of adrenal crisis or recurrence of Cushing’s syndrome, and fosters a holistic approach to endocrine nursing care.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between Addison’s disease and Cushing’s syndrome?

- Addison’s disease is a state of adrenal insufficiency, where the adrenal glands fail to produce enough cortisol and aldosterone, leading to fatigue, hypotension, weight loss, hyperpigmentation, and electrolyte imbalances.

- Cushing’s syndrome is caused by excess cortisol, either from a pituitary tumor (Cushing disease), adrenal tumor, or prolonged steroid use, resulting in central obesity, moon face, hypertension, hyperglycemia, purple striae, and immunosuppression.

How to remember Cushing’s vs Addison’s?

- Mnemonic:

- “CUSHING: C for Cortisol high, U for Upper body fat, S for Sugar high, H for Hypertension, I for Immunosuppression, N for Needing skin care (striae), G for Growth of fat in moon face and buffalo hump.”

- “ADDISON: A for Adrenal insufficiency, D for Darkening of skin (hyperpigmentation), D for Drop in BP, I for Insufficient cortisol, S for Salt craving, O for Overall fatigue, N for Nausea/weight loss.”

What is the triad of Addison’s disease?

- The classic triad includes:

- Hypotension

- Hyperpigmentation

- Electrolyte imbalance (hyponatremia and hyperkalemia)

How to diagnose Cushing syndrome?

- Diagnosis involves a combination of:

- Laboratory tests: Elevated urinary free cortisol, late-night salivary cortisol, and serum cortisol levels.

- Dexamethasone suppression test: Failure to suppress cortisol indicates hypercortisolism.

- Imaging: MRI or CT scans of the pituitary or adrenal glands to identify tumors.

- Nursing roles include preparing patients for tests, ensuring proper sample collection, monitoring vitals, and educating patients about procedures.