ABG Meaning: Mastering Arterial Blood Gas (ABGs) and Interpretation

Arterial blood gas analysis is a critical component of patient assessment, providing a window into the body’s respiratory and metabolic status. Just as vital signs offer a snapshot of cardiovascular health, ABG results reveal how effectively the lungs and kidneys maintain acid-base balance, oxygenation, and carbon dioxide elimination. For nurses, understanding ABGs is essential not only for monitoring patients but also for guiding timely interventions in acute and chronic conditions.

The process of ABG interpretation extends beyond simply reading numerical values. It requires a structured approach to evaluate blood pH, partial pressures of oxygen and carbon dioxide, bicarbonate levels, and compensatory mechanisms. Through this assessment, healthcare providers can detect respiratory or metabolic disturbances, differentiate between acidosis and alkalosis, and determine whether a patient is experiencing a compensated or uncompensated state. These insights are fundamental to making informed decisions about oxygen therapy, ventilation support, and other interventions that directly affect patient outcomes.

In clinical practice, ABG analysis plays a pivotal role across diverse patient populations—from adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or heart failure to neonates and pediatric patients whose normal values differ significantly. Nurses must be proficient in drawing arterial blood samples safely, interpreting measured values accurately, and recognizing variations that signal emerging complications. Even subtle deviations in pH or partial pressures can indicate conditions ranging from respiratory acidosis due to hypoventilation to metabolic alkalosis caused by electrolyte imbalances.

By integrating ABG interpretation into routine nursing assessment, practitioners develop a comprehensive understanding of the patient’s respiratory and metabolic status. This knowledge informs critical decisions about ventilation strategies, oxygen administration, and broader care planning. Furthermore, presenting ABG results clearly—through structured documentation, visual aids, or educational tools—enhances communication with interdisciplinary teams and supports patient-centered care.

This article provides a thorough overview of arterial blood gas testing and interpretation, emphasizing practical applications for nurses. From understanding fundamental parameters and normal ranges to identifying complex acid-base disorders, the discussion equips nursing students and practicing clinicians with the knowledge and confidence needed to translate ABG findings into effective patient care. Through detailed explanations, examples, and guidance on clinical application, readers will gain the skills required to navigate the nuances of ABG interpretation in a variety of healthcare settings.

Introduction to Arterial Blood Gas (ABG)

What is an ABG and Why is it Done?

An arterial blood gas (ABG) test is a diagnostic tool that measures the chemical composition of arterial blood to evaluate a patient’s oxygenation, ventilation, and acid-base balance. Unlike venous blood, which reflects systemic circulation, arterial blood provides direct insight into oxygen and carbon dioxide levels, revealing how efficiently the lungs remove carbon dioxide and supply oxygen to tissues. ABGs are essential for assessing the function of the respiratory system and the body’s metabolic compensation mechanisms, particularly in patients with acute or chronic illnesses.

ABG testing is frequently employed in critical care settings, including intensive care units, emergency departments, and operating theaters, where rapid evaluation of respiratory or metabolic disturbances is crucial. For instance, in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) experiencing exacerbations, ABG results can identify respiratory acidosis due to hypoventilation, guiding interventions such as ventilation support or adjustments in oxygen therapy. Similarly, in cases of heart failure, ABGs provide information about oxygenation status, helping clinicians determine the need for supplemental oxygen or more advanced respiratory support.

The test also plays a significant role in monitoring metabolic disorders. For example, in renal failure, ABG results can detect metabolic acidosis, highlighting the kidney’s inability to maintain bicarbonate balance and acid-base homeostasis. Early recognition of these disturbances allows nurses to implement timely interventions, including fluid management, medication adjustments, or referral to a multidisciplinary team for advanced care.

Understanding ABG Aesthetic and Its Importance in Nursing Practice

The concept of ABG aesthetic refers to the presentation and interpretation of ABG results in a manner that is both clinically informative and visually clear. Effective display of ABG data enhances nursing documentation, facilitates interprofessional communication, and improves patient education. For instance, using tables, color-coded charts, or visual graphs can make complex results more comprehensible, allowing nurses to quickly identify deviations in blood pH, PaCO2, PaO2, or bicarbonate (HCO3⁻) levels.

In educational contexts, innovative platforms like TikTok have been utilized by healthcare educators to create short, visually engaging tutorials on ABG interpretation. Such tools demonstrate stepwise analysis, making it easier for nursing students to learn how to identify acidosis or alkalosis, assess oxygen saturation, and recognize signs of respiratory or metabolic imbalance. By adopting clear and structured ABG presentation methods, nurses can reduce errors in interpretation, ensure patient safety, and support informed decision-making in fast-paced clinical environments.

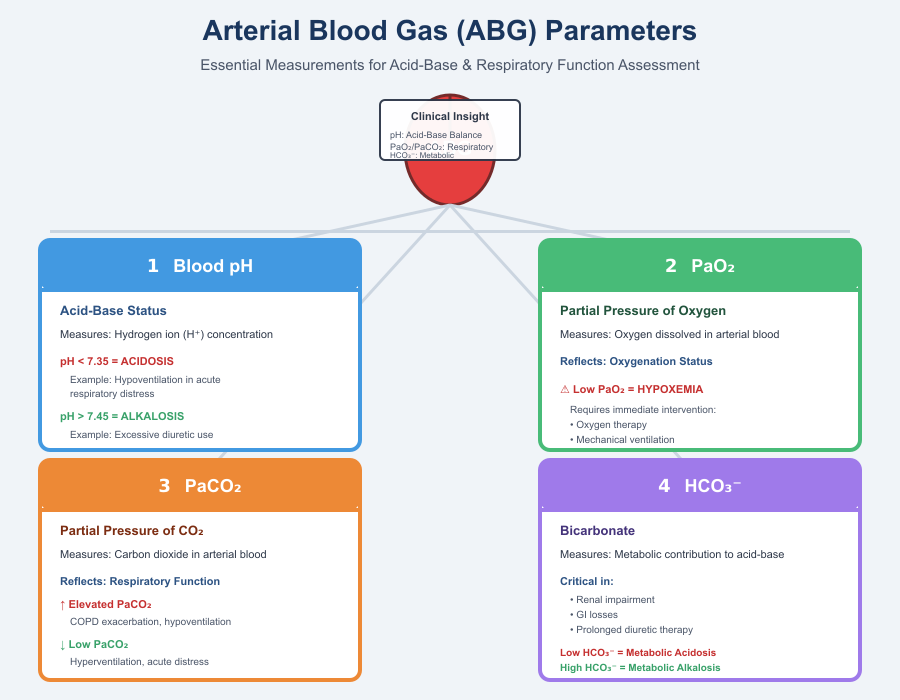

Overview of ABG Parameters Measured: pH, PaO2, PaCO2, HCO3⁻

ABG analysis evaluates four primary parameters, each providing insight into different aspects of respiratory and metabolic function:

- Blood pH – Reflects the hydrogen ion concentration in arterial blood, indicating the acid-base status. A blood pH below 7.35 suggests acidosis, whereas a pH above 7.45 indicates alkalosis. For example, a patient with hypoventilation due to acute respiratory distress may present with respiratory acidosis, while excessive diuretic use could result in metabolic alkalosis.

- Partial Pressure of Oxygen (PaO2) – Measures the amount of oxygen dissolved in arterial blood, reflecting oxygenation status. Low PaO2 values signal hypoxemia, necessitating interventions such as oxygen therapy or mechanical ventilation.

- Partial Pressure of Carbon Dioxide (PaCO2) – Represents the amount of carbon dioxide in your blood, providing information about respiratory function. Elevated PaCO2 may indicate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations or hypoventilation, while low PaCO2 can occur with hyperventilation or acute respiratory distress.

- Bicarbonate (HCO3⁻) – Indicates metabolic contribution to acid-base balance. Altered bicarbonate levels can reveal metabolic acidosis (low HCO3⁻) or metabolic alkalosis (high HCO3⁻). Clinically, this is vital in patients with renal impairment, gastrointestinal losses, or prolonged diuretic therapy.

Nurses interpreting ABG results must consider these parameters collectively rather than in isolation. For instance, an ABG showing low pH, high PaCO2, and normal HCO3⁻ suggests primary respiratory acidosis, whereas low pH with low HCO3⁻ indicates primary metabolic acidosis. Recognizing these patterns informs decisions about ventilation support, oxygen administration, and overall patient management.

In practice, accurate ABG interpretation is critical not only for immediate clinical decision-making but also for ongoing monitoring of patients with pulmonary disease, heart failure, or other conditions that affect gas exchange and acid-base balance. By understanding each parameter and its physiological significance, nurses can anticipate complications, optimize interventions, and contribute to improved patient outcomes.

Performing an ABG Test

How is an Arterial Blood Sample Collected?

Arterial blood sampling is a critical skill for nurses, enabling the assessment of a patient’s oxygenation, ventilation, and acid-base status. Unlike venous blood draws, arterial samples provide direct information about oxygen and carbon dioxide levels in the bloodstream, reflecting the efficiency of the respiratory system. Common sites for arterial blood collection include the radial, brachial, and femoral arteries, with the radial artery often preferred due to accessibility and a lower risk of complications.

Before collection, the nurse should perform an Allen’s test to ensure adequate collateral circulation to the hand, minimizing the risk of ischemia. The patient must be appropriately positioned, typically with the wrist extended and supported to allow easy access to the radial artery. The skin over the puncture site is cleaned using aseptic technique to reduce the risk of infection, and sterile gloves and equipment are essential throughout the procedure.

A pre-heparinized syringe is used to draw the blood, with care to avoid air bubbles, which can artificially alter PaO2 and PaCO2 measurements. Once collected, the sample should be immediately labeled, capped, and transported on ice to the laboratory to preserve accuracy. In contrast to venous blood draws, arterial puncture carries higher risks of bleeding, hematoma, or arterial spasm, requiring careful post-procedure observation and direct pressure at the puncture site for at least five minutes or longer in patients on anticoagulants.

Practical Tips for Drawing ABGs in Adults and Pediatric Patients

Proper technique during arterial blood collection is crucial to minimize patient discomfort and ensure reliable ABG results. In adults, nurses should explain the procedure to reduce anxiety, use local anesthesia when appropriate, and stabilize the artery with firm, gentle pressure during puncture. Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or other pulmonary diseases may have fragile vessels or impaired perfusion, requiring extra caution.

For pediatric patients, including toddlers and school-aged children, positioning is critical. A nurse may use a supine position with the wrist extended or have an assistant hold the child gently but securely. Distraction techniques, such as toys or guided breathing, can reduce anxiety and movement. For difficult draws, smaller-gauge syringes may be employed to reduce discomfort and prevent hematoma formation. Correct technique ensures that the amount of carbon dioxide and oxygen measured reflects the patient’s physiological state rather than procedural artifacts.

Special Considerations for Neonates and Infants

Arterial blood gas interpretation in neonates, including Asian baby and Asian baby girl populations, requires understanding of age-specific normal values and careful sampling technique. Neonates have higher PaO2 and lower PaCO2 compared to adults, and even small deviations can indicate significant respiratory compromise. In this population, the umbilical artery or radial artery is commonly used, with meticulous attention to minimizing trauma and ensuring adequate perfusion.

PaO2 and PaCO2 interpretation in infants is nuanced. For example, premature infants may demonstrate mild metabolic acidosis due to immature renal function and limited bicarbonate buffering capacity. Nurses should monitor oxygen saturation carefully and correlate ABG findings with clinical signs such as tachypnea, cyanosis, or retractions. Using pre-heparinized micro-syringes and rapid sample transport minimizes measurement errors. Additionally, maintaining a calm environment, swaddling the infant, and using warming techniques can improve circulation and reduce stress during blood draw.

By following these procedures, nurses ensure accurate blood gas interpretation, reduce complications, and support timely interventions for neonates, pediatric patients, and adults alike. Mastery of ABG collection techniques is fundamental for monitoring respiratory and metabolic status, guiding ventilation support, and informing oxygen therapy in diverse clinical scenarios.

Understanding Normal ABG Values

Normal Blood pH Range and Its Clinical Significance

The blood pH is a fundamental indicator of the body’s acid-base balance, reflecting the concentration of hydrogen ions in arterial blood. The normal range is 7.35 to 7.45, and maintaining this narrow window is critical for optimal cellular function, enzymatic activity, and systemic homeostasis. Values below 7.35 indicate acidosis, while those above 7.45 suggest alkalosis, each signaling underlying disturbances in either respiratory or metabolic systems.

For example, in patients with acute respiratory distress, hypoventilation can lead to retention of carbon dioxide, lowering blood pH and causing respiratory acidosis. Conversely, excessive hyperventilation in an anxious patient may reduce CO2 excessively, resulting in respiratory alkalosis. Metabolic conditions, such as renal failure, can reduce bicarbonate levels, leading to metabolic acidosis, while prolonged vomiting or diuretic therapy may increase bicarbonate, causing metabolic alkalosis. Understanding the clinical significance of these deviations allows nurses to anticipate complications and implement timely interventions, including adjustments in oxygen therapy or initiation of ventilation support.

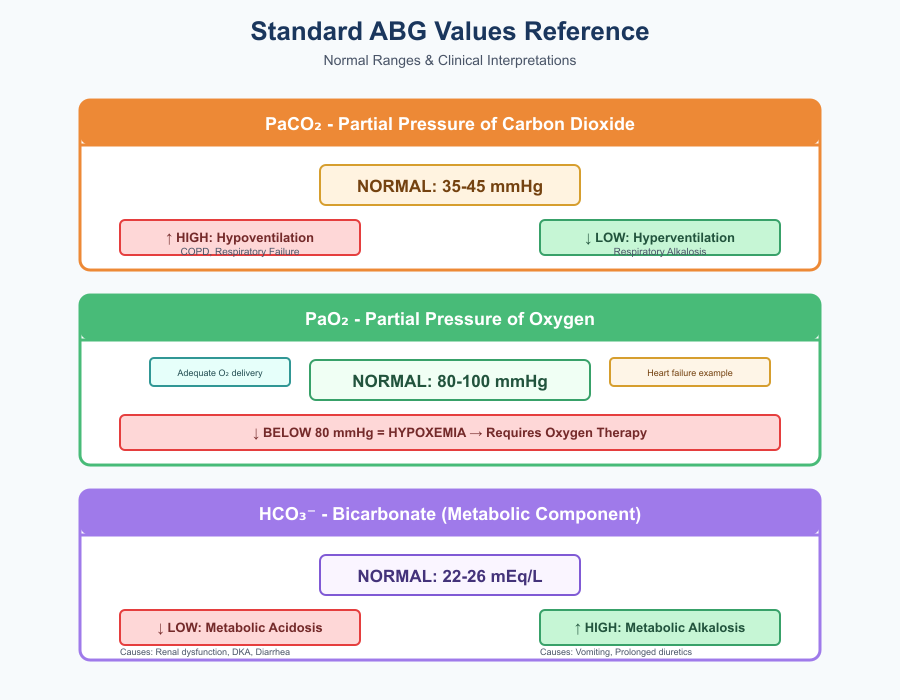

Standard PaCO2, PaO2, and HCO3⁻ Values

Arterial blood gas analysis includes PaCO2, PaO2, and bicarbonate (HCO3⁻), each offering insight into the patient’s respiratory and metabolic status.

- Partial Pressure of Carbon Dioxide (PaCO2): Normal PaCO2 ranges from 35 to 45 mmHg. Elevated levels indicate hypoventilation and a risk of respiratory acidosis, commonly seen in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or acute respiratory failure. Low PaCO2 reflects hyperventilation and possible respiratory alkalosis.

- Partial Pressure of Oxygen (PaO2): Normal PaO2 ranges between 80 and 100 mmHg in adults, indicating adequate oxygen delivery to tissues. Values below this range suggest hypoxemia, prompting oxygen therapy or assessment of ventilation strategies. For example, a patient with heart failure may demonstrate low PaO2 due to pulmonary congestion, necessitating supplemental oxygen and close monitoring.

- Bicarbonate (HCO3⁻): Normal values are 22–26 mEq/L, reflecting the metabolic component of acid-base balance. Low bicarbonate signifies metabolic acidosis, as seen in renal dysfunction, diabetic ketoacidosis, or loss of bicarbonate through diarrhea. Elevated bicarbonate indicates metabolic alkalosis, which may occur due to excessive vomiting or prolonged diuretic therapy.

Nurses must interpret these values collectively, as isolated deviations may be misleading. For instance, a patient with low pH and elevated PaCO2 with normal HCO3⁻ is exhibiting primary respiratory acidosis, whereas a low pH accompanied by low HCO3⁻ suggests metabolic acidosis. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for accurate blood gas interpretation and patient care planning.

Interpreting Base Excess and Oxygen Saturation

Base excess quantifies the metabolic component of acid-base status, reflecting whether there is an excess or deficit of bicarbonate. A positive base excess indicates metabolic alkalosis, while a negative base excess signals metabolic acidosis. For example, in a patient with renal failure, a negative base excess correlates with reduced bicarbonate reabsorption and accumulation of acids, guiding interventions such as bicarbonate supplementation or dialysis support.

Oxygen saturation (SpO2) is a non-invasive measure of hemoglobin-bound oxygen in arterial blood and complements PaO2 values. Nurses monitor SpO2 to assess oxygenation efficiency, adjusting oxygen therapy when saturation falls below safe thresholds. In acute pulmonary conditions, such as acute respiratory distress syndrome, correlating SpO2 with PaO2 ensures precise titration of supplemental oxygen, avoiding both hypoxemia and oxygen toxicity.

By integrating blood pH, PaCO2, PaO2, HCO3⁻, base excess, and oxygen saturation, nurses can form a holistic picture of a patient’s respiratory and metabolic status. This knowledge informs interventions ranging from ventilation support in respiratory failure to fluid and electrolyte management in metabolic disorders, ensuring safe and effective patient care.

ABG Interpretation: Step-by-Step Guide

Systematic Approach to Interpreting ABG Results

Interpreting arterial blood gas (ABG) results requires a structured, methodical approach to ensure accurate assessment of a patient’s respiratory and metabolic status. A systematic evaluation typically follows a sequential framework: first, assess blood pH to determine whether the patient is in an acidosis or alkalosis state. Next, evaluate PaCO2, reflecting respiratory contributions, followed by HCO3⁻, which reflects metabolic involvement. Finally, consider any compensatory mechanisms that the body may have activated to restore acid-base balance.

For example, a patient presenting with acute respiratory distress may have a blood pH below 7.35, indicating acidosis. By reviewing the PaCO2 and HCO3⁻, the nurse can determine whether the disturbance is primarily respiratory (elevated PaCO2) or metabolic (reduced HCO3⁻). Documenting the ABG in a structured manner—listing pH, PaCO2, PaO2, HCO3⁻, base excess, and oxygen saturation—enhances clarity for interdisciplinary communication and supports accurate blood gas interpretation.

Distinguishing Respiratory vs Metabolic Disorders Using PaCO2 and HCO3⁻

A critical step in ABG interpretation is differentiating whether an acid-base disturbance originates from the respiratory system or a metabolic cause.

- Respiratory disorders: A primary respiratory disturbance is indicated when PaCO2 levels are abnormal while HCO3⁻ remains initially within the normal range. For instance, in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbations, patients often exhibit respiratory acidosis, characterized by elevated PaCO2 due to impaired carbon dioxide removal. Conversely, hyperventilation can cause respiratory alkalosis, reflected by a decreased PaCO2 and an elevated pH.

- Metabolic disorders: Primary metabolic disturbances are suggested when HCO3⁻ levels are abnormal, with PaCO2 initially compensating. For example, in renal failure, impaired bicarbonate retention results in metabolic acidosis, lowering blood pH. Patients with prolonged vomiting or excessive bicarbonate administration may develop metabolic alkalosis, indicated by elevated HCO3⁻ levels and high pH.

Recognizing Compensatory Mechanisms in ABG Analysis

The body actively compensates for acid-base disturbances to maintain homeostasis, a concept crucial for blood gas interpretation. Compensation may be partial or complete, depending on whether the pH remains abnormal or returns to the normal range.

- Respiratory compensation for metabolic disorders: In metabolic acidosis, the respiratory system responds by increasing ventilation to expel carbon dioxide, lowering PaCO2 and partially correcting the pH. For instance, a patient with diabetic ketoacidosis may exhibit Kussmaul respirations, a rapid and deep breathing pattern, reflecting respiratory compensation.

- Metabolic compensation for respiratory disorders: In chronic respiratory acidosis, the kidneys retain bicarbonate to buffer excess CO2, gradually normalizing pH. Conversely, in chronic respiratory alkalosis, renal excretion of bicarbonate helps restore acid-base balance.

Recognizing these compensatory mechanisms allows nurses to distinguish between acute versus chronic conditions, anticipate patient deterioration, and implement timely interventions. Failure to consider compensation can lead to misinterpretation—for example, a pH near the normal range may mask an underlying chronic disturbance, such as compensated respiratory acidosis in a COPD patient.

Identifying Acid-Base Disorders

Respiratory Acidosis: Causes, Features, and Clinical Examples

Respiratory acidosis occurs when the lungs fail to adequately remove carbon dioxide (CO2), leading to accumulation in the blood and a decrease in blood pH below 7.35. This condition may be acute or chronic, with distinct clinical implications for nursing care.

Common causes include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), hypoventilation due to neuromuscular disorders, drug-induced respiratory depression from opioids or sedatives, and acute respiratory failure. For instance, a patient experiencing a COPD exacerbation may demonstrate elevated PaCO2, a slightly decreased pH, and compensatory increases in HCO3⁻ if the condition is chronic.

ABG patterns in respiratory acidosis typically show low pH, high PaCO2, and normal or slightly elevated HCO3⁻ in acute cases. Chronic respiratory acidosis may present with partially or fully compensated HCO3⁻ elevation, reflecting renal adaptation.

Nursing interventions focus on improving ventilation and oxygenation. This may include oxygen therapy at controlled concentrations, mechanical ventilation for severe cases, and close monitoring of oxygen saturation and PaO2 to avoid hypoxemia or CO2 retention. Nurses must also assess for signs of altered mental status, headache, and tachycardia, which often accompany elevated CO2 levels.

Metabolic Acidosis: Pathophysiology and Renal Implications

Metabolic acidosis occurs when there is an accumulation of acids or a loss of bicarbonate, leading to a decrease in blood pH. This disorder may be acute or chronic, depending on the underlying cause and the body’s compensatory mechanisms.

Primary causes include renal failure, where impaired kidney function reduces HCO3⁻ retention; diabetic ketoacidosis, which results from excessive ketone production; and severe diarrhea, leading to gastrointestinal loss of bicarbonate. ABG results typically show low pH, low HCO3⁻, and decreased base excess. The PaCO2 may also decrease as the respiratory system compensates by increasing ventilation to remove CO2.

Clinical examples illustrate the importance of timely nursing intervention. A patient with renal failure may present with fatigue, tachypnea, and confusion. ABG interpretation revealing metabolic acidosis with compensatory hyperventilation guides nurses in administering bicarbonate therapy judiciously and monitoring oxygen and carbon dioxide levels to prevent further deterioration.

Metabolic Alkalosis: Clinical Clues and ABG Patterns

Metabolic alkalosis arises from an excess of bicarbonate or loss of hydrogen ions, resulting in blood pH above 7.45. Causes include prolonged vomiting, excessive diuretic therapy, or excessive bicarbonate administration during medical treatment.

ABG patterns typically demonstrate high pH, elevated HCO3⁻, and compensatory hypoventilation, reflected in slightly elevated PaCO2. Clinically, patients may present with muscle cramps, tetany, dizziness, and hypokalemia. Nurses must assess vital signs and electrolyte levels, adjust medications if necessary, and monitor for respiratory suppression, which may occur if hypoventilation persists.

Correct interpretation of ABGs is essential to distinguish metabolic alkalosis from respiratory alkalosis, as interventions differ. Nursing strategies may include addressing the underlying cause, administering electrolyte replacements, and carefully monitoring oxygen saturation and ventilation.

Mixed Disorders: How to Spot Combined Respiratory and Metabolic Issues

Mixed acid-base disorders involve simultaneous respiratory and metabolic disturbances, which can mask traditional ABG patterns and complicate interpretation. For example, a patient with COPD (predisposing to respiratory acidosis) who develops diabetic ketoacidosis may present with ABG values that seem near normal, due to simultaneous compensatory mechanisms.

Identifying mixed disorders requires careful assessment of blood pH, PaCO2, HCO3⁻, and base excess, along with recognition of inconsistencies in expected compensatory patterns. Nurses should consider clinical context, including history of renal disease, pulmonary disorders, or gastrointestinal losses, to detect combined disturbances. Failure to recognize a mixed disorder may delay interventions such as ventilation support or metabolic correction, increasing the risk of rapid deterioration.

A systematic approach includes:

- Determining whether the pH indicates acidosis or alkalosis.

- Assessing PaCO2 and HCO3⁻ for primary disturbances.

- Evaluating the expected compensatory response; deviations may suggest a mixed disorder.

- Correlating ABG findings with clinical signs, such as respiratory distress, altered mental status, or hypotension, to guide timely interventions.

ABGs in Clinical Practice

Guiding Oxygen Therapy and Respiratory Management Based on ABGs

Arterial blood gas (ABG) results play a pivotal role in guiding oxygen therapy and respiratory management. By analyzing PaO2, PaCO2, and blood pH, nurses can determine the patient’s oxygenation status, ventilatory efficiency, and acid-base balance.

For example, a patient presenting with acute respiratory distress may have low PaO2 (<80 mmHg) and elevated PaCO2 (>45 mmHg), indicating hypoxemia and hypercapnia. In this scenario, supplemental oxygen therapy is required to improve tissue oxygenation while monitoring oxygen saturation to avoid both hypoxia and hyperoxia. Nurses adjust delivery methods—such as nasal cannula, non-rebreather mask, or high-flow oxygen—based on ABG findings and respiratory system function.

ABG results also guide ventilation strategies in patients with compromised respiratory function. For instance, in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbations, nurses must balance oxygen supplementation to correct hypoxemia while avoiding excessive oxygen that may blunt the respiratory drive, leading to CO2 retention and respiratory acidosis. Regular monitoring of ABGs allows for titration of ventilation support, including non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) or mechanical ventilation, when necessary.

Continuous blood gas interpretation supports dynamic respiratory management in intensive care units, emergency departments, and post-operative settings, ensuring early detection of deteriorating oxygenation or ventilation and timely interventions.

Using ABG Interpretation to Manage Heart Failure, COPD, and Pulmonary Disease

ABG assessment is equally essential in managing chronic and acute cardiorespiratory conditions, providing insight into the severity of pulmonary disease, cardiac compromise, and systemic hypoxia.

In heart failure, pulmonary congestion may impair oxygen exchange, resulting in low PaO2 and slightly elevated PaCO2. ABG interpretation guides nurses in titrating oxygen therapy, monitoring for early signs of acute respiratory distress, and coordinating interventions such as diuretics to reduce pulmonary edema.

For COPD patients, ABG analysis differentiates between acute respiratory acidosis due to hypoventilation and chronic compensated states. Nurses rely on PaCO2, HCO3⁻, and pH values to adjust ventilation support, implement bronchodilator therapy, and monitor oxygen and carbon dioxide levels to prevent worsening hypercapnia.

Similarly, in pulmonary disease, such as pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), ABGs reveal the extent of hypoxemia, guiding nurses in escalating oxygen therapy, employing prone positioning, or preparing for mechanical ventilation. Clinical examples highlight that patients with PaO2 <60 mmHg or PaCO2 >50 mmHg require urgent intervention to prevent multi-organ dysfunction.

Recognizing Respiratory Failure and the Need for Ventilation

Respiratory failure is indicated on ABGs by critical deviations in PaO2 and PaCO2, often accompanied by abnormal pH. Two primary types exist:

- Hypoxemic respiratory failure (Type I): Characterized by PaO2 <60 mmHg with normal or low PaCO2. Nurses should anticipate the need for oxygen therapy, monitor oxygen saturation, and evaluate the patient for potential intubation if hypoxemia persists despite supplemental oxygen.

- Hypercapnic respiratory failure (Type II): Defined by PaCO2 >50 mmHg and a pH <7.35, reflecting inadequate ventilation. ABG analysis may show respiratory acidosis, often in COPD exacerbations, neuromuscular weakness, or drug-induced respiratory depression. Nursing interventions include supporting ventilation using non-invasive or invasive methods, monitoring PaCO2 trends, and providing patient education on breathing strategies.

Early recognition of respiratory failure is critical. Nurses must correlate ABG findings with clinical signs, such as tachypnea, accessory muscle use, altered mental status, or cyanosis. Prompt escalation of care—including mechanical ventilation, high-flow oxygen therapy, or ICU transfer—prevents complications such as hypoxic injury, arrhythmias, or multi-organ dysfunction.

ABG Interpretation in Special Populations

Pediatric and Neonatal Considerations for ABG Analysis

Interpreting arterial blood gases (ABGs) in neonates and pediatric patients requires a nuanced understanding of age-specific physiology. Unlike adults, children and infants have different normal values for blood pH, PaO2, PaCO2, and HCO3⁻, reflecting their developing respiratory system, metabolic processes, and cardiovascular adaptations.

For example, neonates typically have a slightly lower PaO2 than adults due to the transition from fetal to extrauterine circulation, where oxygen exchange is still stabilizing. PaCO2 levels may be higher in the first days of life because of immature alveolar ventilation. Bicarbonate (HCO3⁻) levels are also slightly lower, reflecting limited renal capacity to regulate acid-base balance. Nurses must interpret ABG results within these normal ranges, rather than adult standards, to avoid misdiagnosis of acidosis or alkalosis.

Age-appropriate interpretation directly informs patient care. In pediatric pulmonary disease or congenital heart disease, early detection of hypoxemia or hypercapnia through ABG analysis enables timely interventions such as oxygen therapy, ventilation support, or fluid management. Failure to recognize these variations may result in inappropriate treatment or delayed escalation of care.

How ABG Values Differ in Newborns and Infants

Newborns and infants, including Asian baby and Asian baby girl populations, present unique ABG characteristics that require careful interpretation.

- PaO2: Neonates naturally have lower partial pressure of oxygen compared to older children and adults, often ranging between 60–80 mmHg. This reflects ongoing adaptation of pulmonary circulation and oxygen transport. Nurses must recognize that a PaO2 of 65 mmHg may be normal for an infant but abnormal for an adult patient.

- PaCO2: Infants often exhibit slightly higher partial pressure of carbon dioxide, typically 40–50 mmHg, due to reduced alveolar ventilation and smaller lung volumes. Elevated PaCO2 in this population must be interpreted cautiously to distinguish between normal physiology and early respiratory compromise.

- Clinical implications: For Asian baby and Asian baby girl populations, genetic, cultural, and environmental factors may influence baseline ABG parameters. Nurses must consider these factors alongside clinical presentation, such as respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, and perfusion, when determining the need for interventions like supplemental oxygen or non-invasive ventilation.

For instance, an Asian baby girl presenting with mild tachypnea and PaO2 of 62 mmHg may be physiologically normal, but ABG interpretation should be combined with pulse oximetry and clinical assessment to guide care.

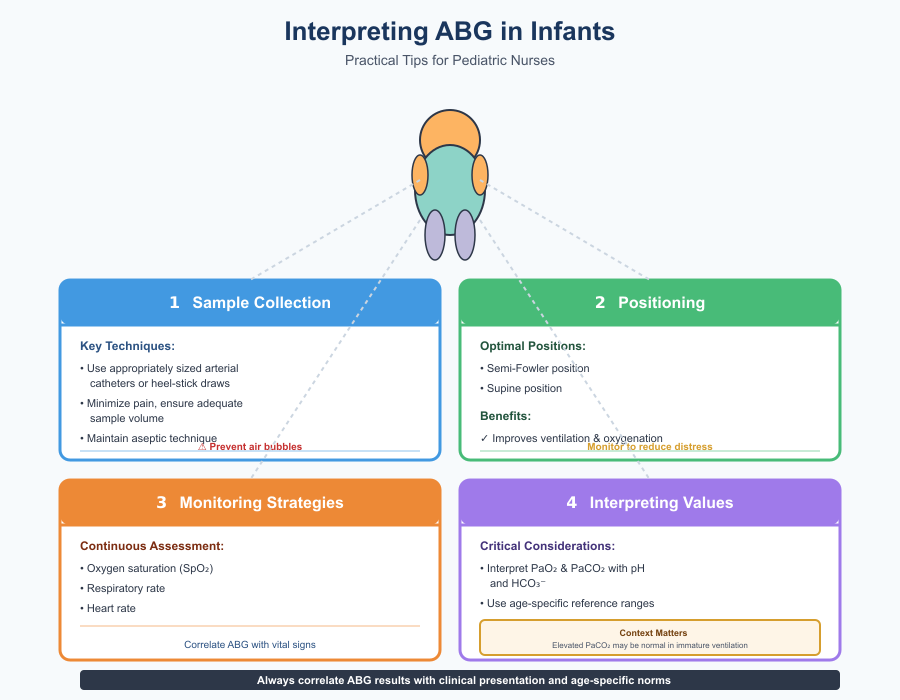

Tips for Interpreting PaO2 and PaCO2 in Infants

Practical guidance for pediatric nurses ensures accurate ABG readings and safe interventions:

- Sample Collection Techniques: Use appropriately sized arterial catheters or heel-stick blood draws for neonates to minimize pain and ensure adequate sample volume. Maintain aseptic technique and prevent air bubbles, which can falsely alter PaO2 and PaCO2 readings.

- Positioning: Proper patient positioning improves ventilation and oxygenation. Semi-Fowler or supine positions are commonly used for infants during arterial sampling, with careful monitoring to reduce distress and movement artifacts.

- Monitoring Strategies: Continuously assess oxygen saturation, respiratory rate, and heart rate during and after the blood draw. Correlate ABG results with these parameters to validate the accuracy of the readings.

- Interpreting Values in Context: Always interpret PaO2 and PaCO2 alongside blood pH and HCO3⁻, considering age-specific reference ranges. For example, slightly elevated PaCO2 may be normal in an infant with immature alveolar ventilation, but the same value in a pediatric patient with respiratory distress indicates respiratory acidosis.

Common Pitfalls in ABG Interpretation

Laboratory Errors and Sample Handling Issues

Accurate ABG interpretation depends not only on clinical knowledge but also on the integrity of the blood sample. Laboratory errors or improper handling can significantly distort results, potentially leading to inappropriate interventions.

Common errors include delayed analysis, exposure of the blood sample to room air, improper anticoagulant use, or sample hemolysis. For example, if an arterial blood gas test sample is left at room temperature for an extended period, PaO2 may falsely increase while PaCO2 decreases due to ongoing gas exchange in the collected blood. Similarly, air bubbles in the blood sample can alter oxygen and carbon dioxide levels, misleading the nurse into overestimating a patient’s oxygenation status.

To minimize errors, nurses should follow standardized protocols:

- Use pre-heparinized syringes and remove air bubbles immediately after blood draw.

- Analyze ABG samples promptly or store them on ice if delays are unavoidable.

- Verify unexpected results with repeat sampling, especially when ABG values conflict with clinical presentation.

By maintaining rigorous handling standards, nurses ensure that PaO2, PaCO2, HCO3⁻, and blood pH accurately reflect the patient’s physiological status, guiding safe oxygen therapy and ventilation management.

Misinterpretation of Mixed Disorders or Compensated States

One of the most frequent challenges in interpreting arterial blood gases is recognizing mixed disorders or compensated acid-base imbalances. These occur when the patient has simultaneous respiratory and metabolic disturbances, or when compensatory mechanisms partially or fully normalize pH.

For example, a patient with COPD (chronic respiratory acidosis) who develops diabetic ketoacidosis may present with near-normal pH, misleading the nurse to assume no acid-base disturbance exists. Similarly, fully compensated metabolic acidosis may mask the severity of the underlying condition if PaCO2 adjustments restore pH to normal.

To avoid misinterpretation, nurses should adopt a stepwise approach:

- Determine if the blood pH indicates acidosis or alkalosis.

- Evaluate PaCO2 and HCO3⁻ to identify the primary disturbance.

- Assess whether compensation is appropriate for the type of disorder; unexpected patterns may indicate a mixed disorder.

- Correlate ABG findings with clinical signs, such as respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, and neurological status, to confirm the physiological context.

This methodical process reduces errors and ensures that interventions—whether oxygen therapy, ventilation support, or pharmacologic treatment—are accurately targeted to the patient’s needs.

Avoiding Common Nursing Mistakes During ABG Assessment

In addition to laboratory and interpretive challenges, nursing errors can affect ABG accuracy. Common pitfalls include:

- Inadequate patient preparation: failing to position the patient appropriately or neglecting to explain the procedure can increase movement artifacts and stress-induced respiratory changes.

- Single measurements without correlation: relying on one ABG result without considering trends or other clinical indicators can lead to incorrect conclusions.

- Incomplete documentation: omitting details such as sample site, oxygen delivery method, or timing may compromise continuity of care.

Practical strategies to avoid mistakes include:

- Repeating ABG measurements when results are inconsistent with the patient’s clinical presentation.

- Documenting all relevant information, including oxygen therapy settings, patient positioning, and recent interventions.

- Using ABG values in conjunction with pulse oximetry, vital signs, and clinical examination to confirm the patient’s respiratory or metabolic status.

- Engaging in continuous education on ABG interpretation, acid-base physiology, and pediatric variations, especially for neonates and Asian baby girl populations.

Conclusion

Mastering ABG interpretation is a cornerstone of safe and effective nursing practice, particularly in critical care, emergency, and pediatric settings. By understanding the physiological significance of PaO2, PaCO2, HCO3⁻, and blood pH, nurses can assess oxygen and carbon dioxide levels, evaluate acid-base balance, and identify early signs of respiratory or metabolic disturbances. Accurate analysis of ABG results informs interventions ranging from oxygen therapy and ventilation support to management of complex conditions such as COPD, heart failure, and metabolic disorders.

Special populations, including neonates, infants, and Asian baby girl patients, require age- and population-specific interpretation, highlighting the need for careful evaluation of PaO2 and PaCO2 in the context of normal ranges and clinical presentation. Equally important is attention to laboratory handling, sample collection, and compensation patterns, as misinterpretation or technical errors can have significant clinical consequences.

Ultimately, proficiency in arterial blood gas analysis empowers nurses to make informed, evidence-based decisions, anticipate complications such as respiratory failure, and tailor interventions to individual patient needs. Through continuous practice, systematic assessment, and integration of ABG findings with patient care and clinical observation, nurses enhance their ability to maintain physiological stability, optimize oxygenation, and deliver high-quality, safe care across diverse populations.

In essence, ABGs are more than numbers—they are a window into a patient’s respiratory and metabolic health, providing actionable insights that guide clinical decisions, improve outcomes, and support the holistic care of patients across all care settings.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does ABG mean in slang terms?

In slang, especially online or on social media, ABG often stands for “Asian Baby Girl”. It’s commonly used to describe style, aesthetic, or cultural identity, particularly in Instagram and TikTok contexts.

What is ABG in medical terms?

In medicine, ABG stands for “Arterial Blood Gas”, a test that measures blood pH, oxygen (PaO2), carbon dioxide (PaCO2), and bicarbonate (HCO3⁻) levels. It assesses oxygenation, ventilation, and acid-base balance in patients.

What is the meaning of ABG in Instagram?

On Instagram, ABG usually refers to “Asian Baby Girl”, often associated with a fashion or aesthetic trend. Posts tagged with #ABG or #ABGAesthetic typically showcase style, makeup, and cultural influences.

How to do an ABG test?

To perform an ABG test:

- Prepare the patient: Explain the procedure, position the patient (usually supine or semi-Fowler), and ensure hand hygiene and PPE.

- Select the artery: Commonly the radial, brachial, or femoral artery. Check collateral circulation using the Allen test if using the radial artery.

- Collect the sample: Use a pre-heparinized syringe, insert the needle at a 30–45° angle into the artery, and withdraw the appropriate blood sample.

- Handle the sample: Remove air bubbles, cap the syringe, and analyze immediately or place on ice if delayed.

- Aftercare: Apply pressure to the puncture site to prevent hematoma or bleeding, monitor the patient, and document the procedure.

This approach ensures accurate ABG results for proper blood gas interpretation and safe patient care.