Metabolic Encephalopathies and Brain Injury

Metabolic encephalopathies are a critical area of study in neurology and nursing, representing a diverse group of disorders that impair brain function through systemic metabolic disturbances rather than localized structural brain disease. These conditions can arise from a variety of underlying causes, including organ dysfunction, metabolic derangements, and exposure to toxins, all of which may affect the brain in acute or chronic ways. For nurses and healthcare professionals, understanding the mechanisms, clinical manifestations, and management strategies for metabolic encephalopathies is essential to prevent brain damage and improve patient outcomes.

At the core of metabolic encephalopathies is the interplay between systemic physiological disturbances and central nervous system function. Conditions such as hepatic encephalopathy and uremic encephalopathy illustrate how organ-specific dysfunction can disrupt the delicate balance of neurotransmission, cerebral metabolism, and toxin clearance, resulting in cognitive impairment, altered mental status, and in severe cases, coma. Toxic metabolic encephalopathies further demonstrate how exogenous substances, medications, or sepsis can precipitate sudden acute metabolic encephalopathy, highlighting the need for vigilance in diverse clinical settings.

Recognition of early symptoms of metabolic encephalopathy, including confusion, agitation, and subtle neurological deficits, is fundamental for timely diagnosis and treatment. Left unaddressed, these conditions may progress to permanent brain damage or acquired brain injury, emphasizing the importance of systematic assessment and monitoring, particularly in high-risk populations and critical care environments such as the intensive care unit. Nursing assessment extends beyond symptom recognition to include evaluation of underlying causes, interpretation of laboratory and imaging studies, and coordination of multidisciplinary interventions to treat metabolic encephalopathy effectively.

This article provides a comprehensive examination of metabolic encephalopathies, exploring their pathophysiology, clinical features, types of metabolic encephalopathies, diagnostic approaches, and evidence-based management strategies. By integrating theoretical knowledge with practical applications, it aims to equip nursing students and clinicians with the tools necessary to identify, evaluate, and manage patients experiencing these complex neurological conditions. Understanding these disorders not only enhances clinical judgment but also supports the delivery of safe, patient-centered care, mitigating the risk of brain injury and optimizing recovery.

Understanding Metabolic Encephalopathies

Pathophysiology and Mechanisms of Brain Injury

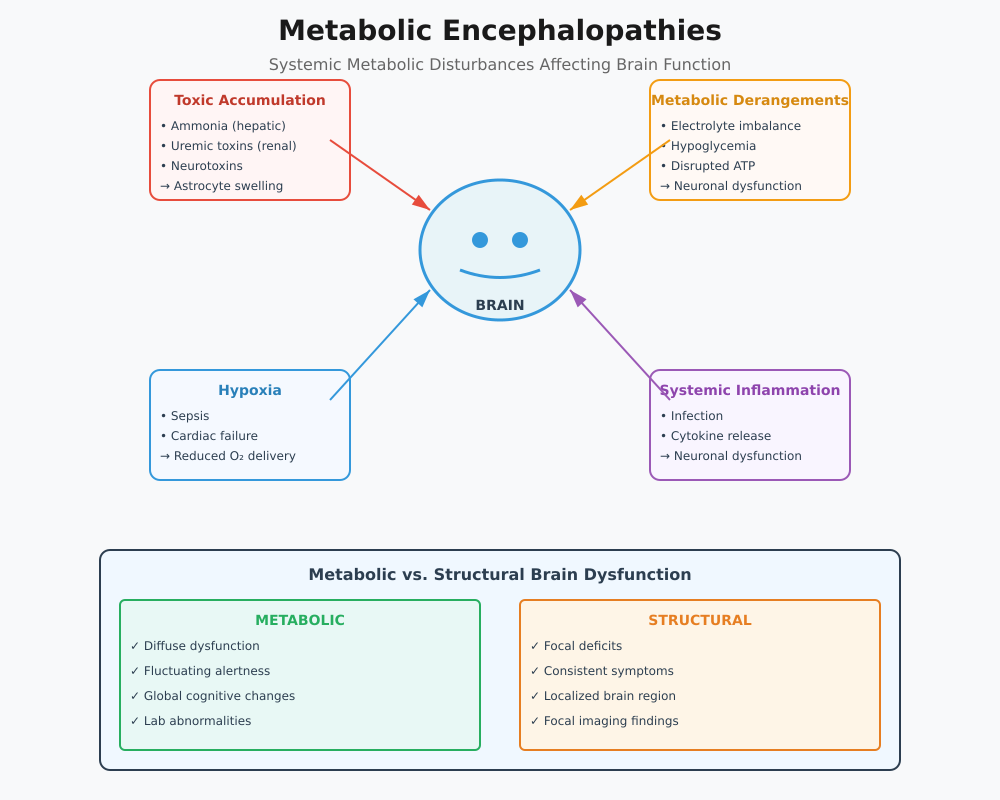

Metabolic encephalopathies represent a diverse group of disorders where systemic metabolic disturbances affect neuronal function, leading to widespread brain dysfunction rather than focal structural brain disease. The pathophysiology involves several overlapping mechanisms:

- Accumulation of Toxic Substances

- In hepatic encephalopathy, impaired liver function results in ammonia and other neurotoxins entering the brain, leading to astrocyte swelling, neurotransmitter imbalance, and impaired synaptic transmission.

- Similarly, uremic encephalopathy arises when renal failure prevents adequate clearance of nitrogenous wastes, causing neuronal excitotoxicity.

- Example: A patient with acute liver failure may rapidly develop acute encephalopathy characterized by confusion, disorientation, and lethargy due to elevated ammonia levels.

- Metabolic Derangements

- Electrolyte imbalances (e.g., hyponatremia, hypercalcemia) disrupt neuronal membrane potentials, impair synaptic signaling, and can precipitate acute metabolic encephalopathy.

- Hypoglycemic encephalopathy illustrates how low glucose delivery to the brain interrupts ATP production, affecting brain function and potentially causing seizures or permanent brain damage.

- Hypoxia and Impaired Oxygen Delivery

- Conditions such as sepsis-associated encephalopathy or cardiac failure reduce oxygen supply to the central nervous system, exacerbating neuronal injury and contributing to acquired brain injury.

- Acute metabolic derangements often combine hypoxia with toxin accumulation, creating a synergistic risk for brain injury.

- Systemic Inflammatory Effects

- In toxic metabolic encephalopathies, systemic inflammation or infection triggers cytokine-mediated neuronal dysfunction, which may present as acute encephalopathy with fluctuating neurological symptoms.

Clinical Implications:

- Early recognition is critical. Patients with metabolic encephalopathy often present with subtle altered mental status, which may progress to coma if underlying causes are not addressed.

- Nursing assessment should include monitoring for signs of brain dysfunction caused by systemic metabolic changes and awareness of severity of encephalopathy to prevent permanent brain damage.

Differentiating Metabolic from Structural Brain Dysfunction

Correctly distinguishing metabolic encephalopathies from structural brain disease is essential for accurate diagnosis, intervention, and prevention of brain injury. Key differences include:

- Distribution of Dysfunction

- Metabolic encephalopathy: Typically diffuse; affects cognition, attention, and consciousness globally.

- Structural brain disease: Focal; deficits correspond to specific brain regions (e.g., hemiparesis in stroke).

- Clinical Presentation

- Metabolic encephalopathies often manifest with:

- Confusion and disorientation

- Fluctuating alertness

- Acute changes in behavior or cognition

- Structural lesions usually present with:

- Focal neurological deficits

- Consistent motor or sensory impairments

- Metabolic encephalopathies often manifest with:

- Diagnostic Evaluation

- Laboratory assessments and metabolic panel help identify systemic causes of encephalopathy in patients.

- Imaging (e.g., CT appearances in metabolic encephalopathies due to systemic causes) may reveal diffuse cerebral edema, whereas focal lesions suggest structural brain disease or hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy.

- Continuous neurological symptoms monitoring in the intensive care unit allows for early intervention.

- Nursing Considerations

- Focused assessment of symptoms of metabolic encephalopathy, including subtle changes in cognition, is critical.

- Rapid implementation of treatment options targeting the underlying cause (e.g., correcting glucose, electrolytes, or reducing neurotoxin levels) is essential to prevent brain damage.

Example:

A patient admitted with severe liver failure develops hepatic encephalopathy. Nursing staff note early altered mental status, confusion, and lethargy. Rapid initiation of lactulose therapy to reduce ammonia, combined with monitoring in the intensive care unit, prevents progression to coma and acquired brain injury. In contrast, a patient with a middle cerebral artery infarct would exhibit hemiparesis and aphasia, illustrating the difference between metabolic and structural brain dysfunction.

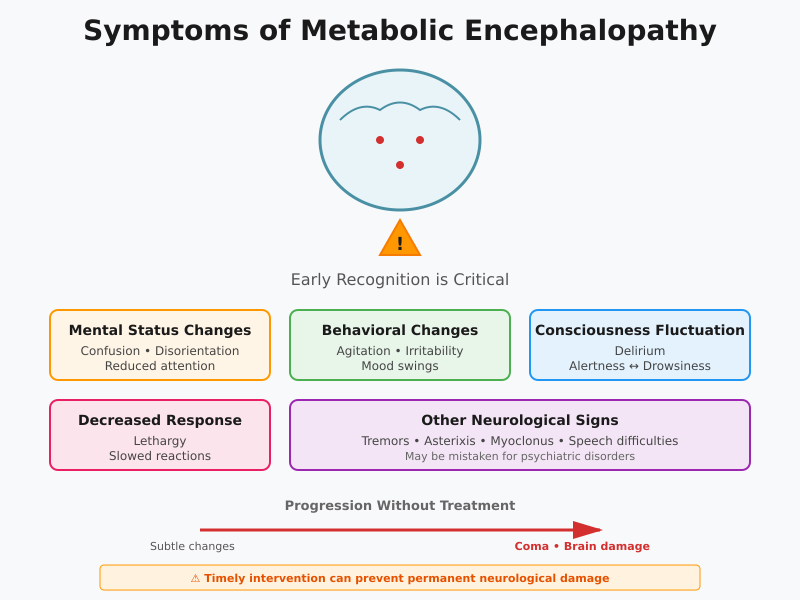

Symptoms of Metabolic Encephalopathy

Acute Signs and Altered Mental Status

Metabolic encephalopathy can present with a wide spectrum of neurological symptoms, ranging from subtle cognitive changes to profound acute metabolic encephalopathy. Recognizing early signs and symptoms is essential, as timely intervention can prevent coma and permanent brain damage.

Common acute manifestations include:

- Altered mental status

- Confusion, disorientation, and reduced attention span.

- Patients may appear withdrawn or inattentive to their environment.

- Behavioral changes

- Agitation, irritability, and emotional lability.

- Sudden mood swings or unusual behavior may indicate early acute encephalopathy.

- Delirium and fluctuating consciousness

- Patients may oscillate between periods of alertness and drowsiness.

- These fluctuations often correlate with the severity of metabolic disturbances.

- Lethargy and decreased responsiveness

- Progressive slowing of motor and cognitive responses.

- May precede more severe brain dysfunction caused by ongoing metabolic insult.

- Other neurological signs

- Tremors, asterixis (flapping tremor in hepatic encephalopathy), myoclonus, or subtle speech difficulties.

- These symptoms may initially be mistaken for psychiatric disturbances if metabolic causes are not considered.

Example:

A patient with chronic liver disease develops early hepatic encephalopathy. Nursing observation detects confusion, mild agitation, and intermittent sleep disturbances. Recognizing these acute signs and altered mental status prompts timely initiation of lactulose therapy, preventing progression to coma.

Clinical Implication:

Early identification and documentation of these symptoms of metabolic encephalopathy are critical in the intensive care unit or ward setting, where patients are at risk of rapid neurological deterioration due to acute metabolic derangements. Nurses play a central role in monitoring changes and communicating findings to the multidisciplinary team for management of metabolic encephalopathy.

Progression to Coma and Acquired Brain Injury

If metabolic encephalopathy often goes unrecognized or untreated, it may progress to coma and acquired brain injury. Understanding the risk factors for severe neurological deterioration and the timeline for irreversible brain damage is essential for effective clinical intervention.

Key Risk Factors Include:

- Severe organ dysfunction

- Advanced liver, kidney, or endocrine failure.

- Uncorrected metabolic disturbances like hyponatremia, hyperammonemia, or hypoglycemia.

- Toxin accumulation

- Toxic metabolic encephalopathies caused by medications, alcohol, or systemic infections can precipitate rapid decline.

- Hypoxia or impaired cerebral perfusion

- Hypoxic encephalopathy or sepsis-associated encephalopathy exacerbates neuronal injury.

- Pre-existing neurological vulnerability

- Elderly patients or those with structural brain disease or prior acquired brain injury are more susceptible.

Timeline for Progression:

- Early stages: subtle altered mental status and mild cognitive impairment.

- Intermediate: pronounced confusion, agitation, acute encephalopathy, and impaired motor coordination.

- Severe: coma, seizures, or persistent brain dysfunction caused by prolonged metabolic derangements, leading to permanent brain damage.

Example:

A patient with uremic encephalopathy secondary to renal failure presents with mild confusion and drowsiness. Delayed initiation of dialysis and electrolyte correction allows acute metabolic encephalopathy to progress, resulting in coma and early signs of acquired brain injury on imaging. Nursing vigilance in monitoring symptoms and signs can prevent such outcomes.

Clinical Implication:

Rapid recognition of acute encephalopathy symptoms enables early interventions such as:

- Correction of metabolic imbalances (glucose, electrolytes)

- Initiation of targeted therapies for hepatic encephalopathy, uremic encephalopathy, or other toxic and acquired metabolic encephalopathies

- Close observation in the intensive care unit for patients at risk of severe encephalopathy and brain injury

Causes and Risk Factors

Toxic Metabolic Encephalopathies

Toxic metabolic encephalopathies are disorders in which the brain is affected by toxic metabolic substances, often originating from drugs, environmental toxins, or systemic exposure to neuroactive chemicals. These conditions represent a cause metabolic encephalopathy that is preventable in many cases if early identification occurs.

Common contributors include:

- Medications and pharmacologic agents: Sedatives, opioids, antipsychotics, or chemotherapy agents can precipitate toxic metabolic encephalopathy in susceptible patients, especially those with underlying organ dysfunction.

- Exogenous toxins: Carbon monoxide, heavy metals, or solvents can disrupt brain function and induce acute or chronic neurological symptoms.

- Systemic toxins from infection or sepsis: Sepsis-associated encephalopathy is mediated by inflammatory cytokines that alter cerebral metabolism and neurotransmission.

Example:

A patient receiving high-dose sedatives postoperatively develops confusion, agitation, and fluctuating consciousness. Laboratory tests reveal mild renal impairment, which slows drug clearance. This scenario illustrates toxic metabolic encephalopathies caused by exogenous agents, emphasizing the importance of dose adjustment and monitoring.

Clinical Implications:

- Nurses should monitor for early signs and symptoms of toxic metabolic encephalopathy in patients receiving high-risk medications or exposed to environmental toxins.

- Prompt identification allows clinicians to adjust or discontinue the offending agent, initiate supportive care, and prevent progression to coma or acquired brain injury.

Acquired Metabolic Encephalopathies

Acquired metabolic encephalopathies result from metabolic encephalopathies due to systemic conditions affecting brain metabolism indirectly, rather than from direct neurotoxicity. These are some of the most common causes of diffuse brain injury in hospitalized patients.

Major systemic causes include:

- Liver failure – leading to hepatic encephalopathy

- Renal failure – causing uremic encephalopathy

- Hypoglycemia – precipitating hypoglycemic encephalopathy

- Sepsis – contributing to sepsis-associated encephalopathy

- Electrolyte imbalances and metabolic disturbances – including hyponatremia, hypercalcemia, and metabolic acidosis

Example:

An elderly patient with chronic kidney disease develops metabolic encephalopathies due to systemic accumulation of uremic toxins. Early recognition of subtle cognitive changes and initiation of dialysis prevented progression to acute metabolic encephalopathy and permanent brain damage.

Clinical Implications:

- Nurses must maintain vigilance for subtle cognitive or behavioral changes in patients with acquired metabolic encephalopathies.

- Early intervention targeting the underlying cause—such as fluid and electrolyte management, renal replacement therapy, or infection control—is essential to prevent brain injury.

Hepatic Encephalopathy and Liver Dysfunction

Hepatic encephalopathy is a prototype of metabolic encephalopathy caused by liver dysfunction. The primary underlying cause is the accumulation of neurotoxins, particularly ammonia, which crosses the blood-brain barrier, alters neurotransmission, and causes cerebral edema in severe cases.

Mechanism of Neurotoxin Accumulation:

- Reduced detoxification of ammonia and other nitrogenous waste products in liver failure.

- Disruption of the gut-liver-brain axis, allowing gut-derived toxins to circulate systemically.

- Altered cerebral energy metabolism, leading to impaired brain function.

Clinical Implications for Brain Injury:

- Early manifestations include confusion, asterixis, and sleep disturbances.

- If untreated, patients can progress to coma, seizures, and acquired brain injury.

- Nursing assessment focuses on monitoring mental status, ammonia levels, and early interventions such as lactulose therapy to reduce toxin accumulation.

Example:

A patient with cirrhosis presents with mild confusion and tremors. Nursing recognition of early hepatic encephalopathy and administration of lactulose prevents deterioration to severe encephalopathy and permanent brain damage.

Hypoglycemic and Uremic Encephalopathy

Hypoglycemic encephalopathy and uremic encephalopathy illustrate how acute metabolic derangements can precipitate acute encephalopathy.

- Hypoglycemic Encephalopathy

- Caused by a sudden drop in blood glucose, often in diabetic patients on insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents.

- Rapid depletion of neuronal energy disrupts neurotransmission, leading to confusion, agitation, or seizures.

- If uncorrected, can progress to coma and permanent brain damage.

- Uremic Encephalopathy

- Occurs in patients with acute or chronic renal failure due to the accumulation of uremic toxins.

- Manifests as lethargy, impaired cognition, myoclonus, and in severe cases, acquired brain injury.

- Early dialysis and correction of electrolyte imbalances are critical for management of metabolic encephalopathy.

Prevention Strategies and Clinical Monitoring:

- Frequent monitoring of blood glucose and renal function in high-risk patients.

- Prompt recognition of neurological symptoms and early intervention to correct the underlying cause.

- Nursing staff in the intensive care unit must implement continuous mental status checks and coordinate multidisciplinary care to prevent progression to coma or irreversible brain dysfunction.

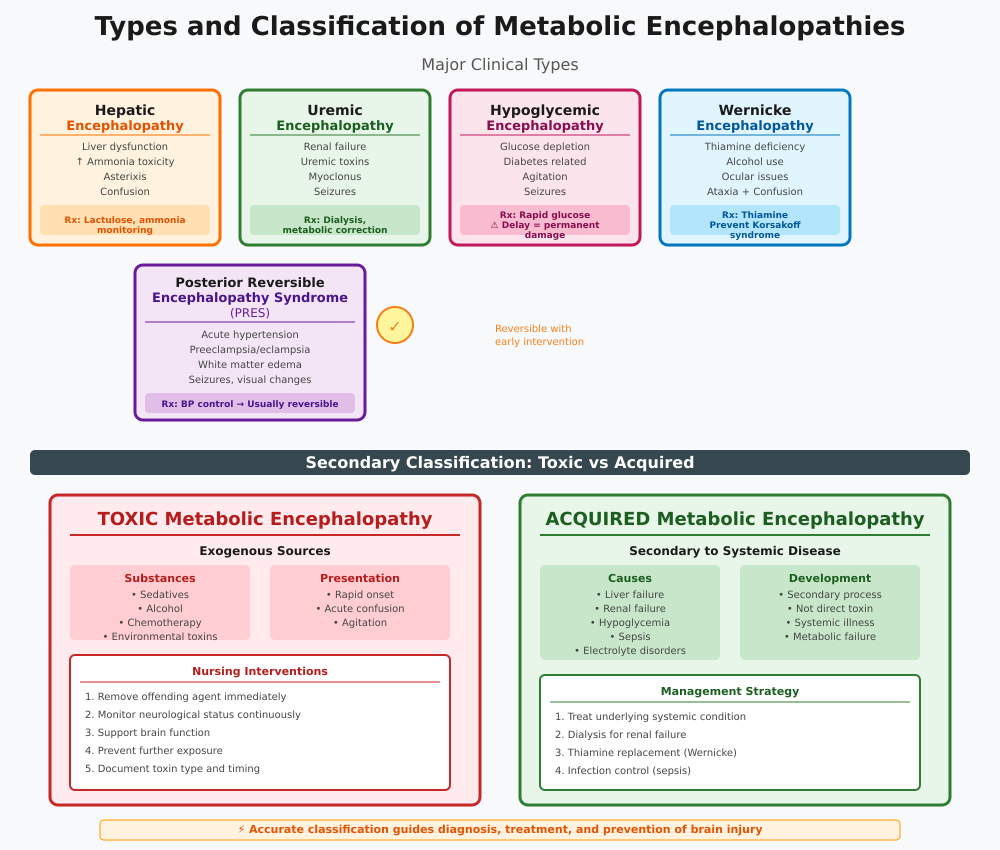

Types and Classification of Metabolic Encephalopathies

Understanding the types of metabolic encephalopathies is crucial for accurate diagnosis of metabolic encephalopathy, appropriate intervention, and prevention of brain injury. These disorders are classified based on etiology, pathophysiology, and clinical presentation, and can broadly be divided into major clinical types and the distinction between toxic and acquired metabolic encephalopathies.

Major Clinical Types

The types of metabolic encephalopathies commonly encountered in clinical practice include:

- Hepatic Encephalopathy

- Caused by liver dysfunction, typically in cirrhosis, acute liver failure, or portosystemic shunting.

- Pathophysiology: Accumulation of neurotoxins such as ammonia impairs astrocyte function and neurotransmission, leading to brain dysfunction caused by metabolic derangements.

- Clinical presentation: Confusion, asterixis, sleep disturbances, and in severe cases, coma.

- Example: A patient with decompensated cirrhosis exhibits early altered mental status. Nursing staff initiate lactulose therapy and monitor ammonia levels, preventing progression to acquired brain injury.

- Uremic Encephalopathy

- Occurs in chronic or acute renal failure due to accumulation of uremic toxins.

- Symptoms may include lethargy, myoclonus, seizures, and cognitive impairment.

- Management requires dialysis and correction of metabolic imbalances.

- Hypoglycemic Encephalopathy

- Results from acute glucose depletion, often in diabetic patients on insulin or hypoglycemic agents.

- Acute neurological symptoms such as confusion, agitation, and seizures are common.

- Rapid glucose administration can reverse brain dysfunction, but delayed recognition may cause permanent brain damage.

- Wernicke Encephalopathy

- Caused by thiamine deficiency, often associated with chronic alcohol use or malnutrition.

- Characterized by the classic triad of ocular disturbances, ataxia, and confusion.

- Timely thiamine replacement can prevent progression to Korsakoff syndrome and long-term acquired brain injury.

- Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome (PRES)

- Associated with acute hypertension, preeclampsia/eclampsia, renal failure, or immunosuppressive therapy.

- CT appearances in metabolic encephalopathies due to PRES often show bilateral posterior white matter edema.

- Clinically presents with seizures, visual disturbances, headache, and confusion. Early recognition and blood pressure control usually allow full recovery, highlighting the reversible nature of this metabolic encephalopathy.

Toxic vs Acquired Metabolic Encephalopathies

Beyond the individual clinical types, metabolic encephalopathies can also be categorized into toxic and acquired metabolic encephalopathies, which has important nursing implications for prevention and management.

- Toxic Metabolic Encephalopathies

- Caused by exogenous toxins or drugs, including sedatives, chemotherapy agents, alcohol, and environmental toxins.

- Symptoms may develop rapidly, often presenting as acute confusion, agitation, or acute metabolic encephalopathy.

- Nursing interventions focus on removing the offending agent, monitoring neurological symptoms, and supporting brain function.

- Acquired Metabolic Encephalopathies

- Result from metabolic encephalopathies due to systemic conditions such as liver failure, renal failure, hypoglycemia, sepsis, or electrolyte disturbances.

- These encephalopathies develop secondary to systemic disease rather than direct neurotoxin exposure.

- Management of metabolic encephalopathy requires correcting the underlying cause, such as initiating dialysis for renal failure, administering thiamine for Wernicke encephalopathy, or controlling infection in sepsis-associated encephalopathy.

Distinguishing Features:

| Feature | Toxic Metabolic | Acquired Metabolic |

|---|---|---|

| Cause | Exogenous drugs, toxins | Systemic organ failure or metabolic disorder |

| Onset | Often rapid | Gradual or acute depending on systemic insult |

| Reversibility | Often reversible if agent removed | Depends on timeliness of treatment of underlying cause |

| Nursing Focus | Identification of toxins, withdrawal of offending agent | Management of underlying cause, monitoring for permanent brain damage |

Example:

- A postoperative patient develops toxic metabolic encephalopathy after opioid administration combined with impaired renal clearance. Immediate medication adjustment and monitoring prevent acute encephalopathy progression.

- Conversely, a patient with chronic liver failure develops hepatic encephalopathy (acquired metabolic encephalopathy). Nursing staff monitor mental status, administer lactulose, and implement dietary protein modifications to prevent brain injury.

Diagnosis of Metabolic Encephalopathies

Accurate diagnosis and treatment of metabolic encephalopathies is critical to prevent progression to coma or permanent brain damage. Because metabolic encephalopathy may present subtly, early recognition requires systematic clinical assessment, laboratory testing, imaging, and ICU protocols for high-risk patients.

Clinical Assessment and Recognition

The first step in diagnosing metabolic encephalopathy is thorough clinical assessment. Encephalopathy diagnosed at an early stage allows prompt interventions and improves outcomes.

Key components include:

- Mental Status Examination

- Assess orientation, attention, memory, and cognition.

- Look for altered mental status such as confusion, disorientation, agitation, or lethargy.

- Example: A patient with early hepatic encephalopathy may appear drowsy, have slowed speech, and demonstrate impaired short-term memory.

- Neurological Assessment

- Evaluate motor function, reflexes, coordination, and cranial nerves.

- Observe for subtle signs of neurological symptoms, such as asterixis in hepatic encephalopathy or myoclonus in uremic encephalopathy.

- Early Warning Signs

- Fluctuating consciousness, sleep-wake disturbances, or sudden behavioral changes often precede acute metabolic encephalopathy.

- Nursing staff must document and escalate any symptoms of metabolic encephalopathy, as early detection is key to treatment of metabolic encephalopathy and prevention of brain injury.

Laboratory and Imaging Investigations

Objective investigations confirm the diagnosis of metabolic encephalopathy and help identify the underlying cause.

1. Laboratory Investigations

- Metabolic panels: Assess electrolytes, acid-base balance, glucose, and renal function.

- Liver function tests: Elevated bilirubin, AST, ALT, and ammonia suggest hepatic encephalopathy.

- Renal function tests: Elevated BUN and creatinine may indicate uremic encephalopathy.

- Other tests: Thiamine levels for suspected Wernicke encephalopathy; infection markers in sepsis-associated encephalopathy.

2. Imaging Studies

- CT or MRI scans may be performed to evaluate CT appearances in metabolic encephalopathies and exclude focal structural lesions.

- Appearances in metabolic encephalopathies due to systemic causes typically include:

- Diffuse cerebral edema

- Symmetric white matter changes (e.g., in PRES)

- Lack of localized infarction, which helps differentiate from structural brain disease

Example:

A patient with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome exhibits seizures and visual disturbances. MRI reveals bilateral posterior white matter edema without focal infarction, confirming the metabolic rather than structural nature of the encephalopathy diagnosed.

Excluding Structural Brain Injury

Differentiating metabolic encephalopathy from structural brain disease is critical to avoid misdiagnosis.

Approach:

- Compare imaging findings to clinical presentation:

- Diffuse cognitive changes suggest metabolic origin

- Focal neurological deficits indicate structural brain disease

- Rule out hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: Consider patient history of cardiac arrest, respiratory failure, or hypotension.

- Evaluate for prior acquired brain injury or chronic traumatic encephalopathy, which may mimic metabolic symptoms.

Clinical Implication:

- Nurses must recognize subtle signs that suggest metabolic rather than structural causes, ensuring appropriate diagnosis of metabolic encephalopathy and timely management of metabolic encephalopathy.

Intensive Care Unit Diagnostic Protocols

Patients with severe or rapidly progressive encephalopathy often require intensive care unit admission for close monitoring and systematic evaluation.

ICU protocols include:

- Continuous Neurological Monitoring

- Frequent GCS assessment and mental status checks

- Observation for neurological symptoms indicating progression to coma

- Laboratory and Metabolic Monitoring

- Hourly glucose checks in hypoglycemic encephalopathy

- Electrolyte monitoring and renal/hepatic panels for metabolic encephalopathies due to systemic causes

- Imaging and Diagnostic Evaluation

- Early CT or MRI to assess CT appearances in metabolic encephalopathies

- EEG may be used to detect subclinical seizure activity

- Multidisciplinary Assessment

- Coordination between nursing staff, neurologists, nephrologists, hepatologists, and intensivists

- Early recognition of acute metabolic encephalopathy allows rapid initiation of treatment of metabolic encephalopathy and prevention of acquired brain injury

Example:

An ICU patient with sepsis develops confusion and agitation. Serial labs reveal metabolic acidosis, elevated ammonia, and acute kidney injury. Nurses implement diagnosing metabolic protocols, coordinate with the medical team, and initiate interventions to correct the underlying cause, preventing progression to severe encephalopathy.

Treatment and Management

The treatment of metabolic encephalopathy is a time-sensitive process that focuses on stabilizing the patient, preventing brain injury, addressing the underlying cause, and, in severe cases, providing intensive care unit support. Early intervention significantly improves outcomes and prevents progression to coma or permanent brain damage. Nurses play a pivotal role in monitoring, early recognition, and initiating appropriate interventions.

Immediate Interventions for Acute Encephalopathy

Acute metabolic encephalopathy represents a neurological emergency. Early intervention ensures encephalopathy treated before brain dysfunction becomes irreversible.

Key stabilization measures include:

- Airway, Breathing, and Circulation (ABCs)

- Ensure adequate oxygen delivery to prevent hypoxic injury.

- Monitor vital signs continuously, as hypotension, hypoxia, or hypoglycemia can exacerbate acute encephalopathy.

- Example: A patient with hepatic encephalopathy and decreased consciousness may require oxygen supplementation and airway protection.

- Correction of Metabolic Derangements

- Rapid identification and correction of glucose, electrolytes, and acid-base imbalances.

- Intravenous glucose for hypoglycemic encephalopathy, sodium correction for hyponatremia, or bicarbonate for metabolic acidosis.

- Prevention of Brain Injury and Management of Coma

- Positioning to prevent aspiration, pressure injury prevention, and frequent neurological assessments.

- Use of GCS to monitor severity of encephalopathy.

- In cases where coma develops, supportive care includes airway protection, sedation if needed, and seizure monitoring.

Clinical Example:

An elderly diabetic patient presents with confusion and lethargy due to severe hypoglycemia. Immediate administration of intravenous dextrose stabilizes glucose, preventing progression to coma and acquired brain injury.

Targeted Treatment for Underlying Causes

Effective management requires addressing the underlying cause that triggers the cause encephalopathy. Treatment strategies differ based on the specific metabolic derangement.

- Liver Failure – Hepatic Encephalopathy

- Reduce ammonia accumulation using lactulose or rifaximin.

- Monitor liver function, electrolytes, and nutritional intake.

- Example: Nursing interventions include frequent mental status checks and dietary protein adjustments to minimize neurotoxin load.

- Renal Failure – Uremic Encephalopathy

- Initiate dialysis or adjust dialysis schedule in chronic kidney disease.

- Correct electrolyte imbalances and manage fluid status.

- Continuous nursing assessment is essential to monitor neurological symptoms and prevent brain injury.

- Hypoglycemia

- Rapid glucose administration intravenously or orally, depending on severity.

- Monitor glucose levels and neurological status post-treatment to ensure encephalopathy treated.

- Sepsis-Associated Encephalopathy

- Aggressive infection control: antibiotics, fluid resuscitation, and hemodynamic support.

- Nursing assessment focuses on early detection of acute metabolic encephalopathy through mental status and vital sign monitoring.

- Other Metabolic Derangements

- Electrolyte correction (sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium)

- Acid-base correction in metabolic acidosis

- Nutritional support in vitamin deficiencies such as thiamine deficiency leading to Wernicke encephalopathy

Clinical Example:

A patient in ICU with sepsis develops acute metabolic encephalopathy. Nurses initiate continuous monitoring, administer fluids and antibiotics, and correct electrolyte imbalances. Early intervention stabilizes brain function and prevents permanent brain damage.

Advanced Treatment and ICU Management

Patients with severe or refractory toxic and acquired metabolic encephalopathies may require intensive care unit admission for continuous monitoring and advanced interventions.

Key ICU strategies include:

- Criteria for ICU Admission

- Severe encephalopathy, progressing acute metabolic encephalopathy, coma, or multi-organ dysfunction.

- Unstable vital signs or need for invasive monitoring and airway protection.

- Multidisciplinary Care

- Collaborative care between nursing staff, intensivists, nephrologists, hepatologists, and neurologists.

- Daily review of laboratory parameters, neurological status, and metabolic panels to guide ongoing interventions.

- Continuous Monitoring

- Frequent mental status exams using GCS or CAM-ICU.

- Cardiorespiratory monitoring to prevent secondary brain injury.

- Regular assessment of treatment options effectiveness, including medication titration and metabolic correction.

Clinical Example:

A patient with hepatic encephalopathy and sepsis is admitted to the intensive care unit. Nursing staff coordinate lactulose administration, monitor ammonia levels, track mental status, and assist with hemodynamic support. Early recognition and intervention stabilize the patient, demonstrating effective management of metabolic encephalopathy.

Conclusion

Metabolic encephalopathies represent a spectrum of reversible and potentially life-threatening conditions that profoundly affect brain function. These disorders, whether toxic and acquired metabolic encephalopathies, hepatic encephalopathy, uremic encephalopathy, or hypoglycemic encephalopathy, share a common mechanism: systemic metabolic disturbances disrupt neuronal activity, impair neurotransmission, and, if untreated, can progress to coma or acquired brain injury.

Early recognition of symptoms of metabolic encephalopathy, including confusion, agitation, delirium, and lethargy, is essential for preventing permanent brain damage. Nursing vigilance, timely clinical assessment, and careful monitoring of altered mental status are critical components of care. Nurses play a pivotal role in identifying subtle changes, initiating treatment of metabolic encephalopathy, and coordinating with multidisciplinary teams to correct underlying causes such as liver failure, renal dysfunction, hypoglycemia, or sepsis.

The distinction between metabolic and structural brain injury guides both diagnosing metabolic encephalopathy and implementing targeted interventions. Laboratory evaluation, imaging studies including CT appearances in metabolic encephalopathies, and metabolic panels provide objective evidence for diagnosis and treatment. In severe cases, management in the intensive care unit ensures continuous monitoring, early intervention, and prevention of brain injury progression.

Ultimately, effective management of metabolic encephalopathies relies on a comprehensive approach that combines rapid recognition, correction of metabolic derangements, treatment of the underlying cause, and vigilant nursing care. By understanding the types of metabolic encephalopathies, their pathophysiology, and clinical manifestations, healthcare professionals can mitigate complications, preserve brain function, and improve patient outcomes. For nursing students and clinicians, mastery of these principles ensures that patients at risk of acute metabolic encephalopathy receive timely, evidence-based interventions that prevent coma and optimize neurological recovery.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most common cause of metabolic encephalopathy?

The most common cause is hepatic dysfunction, leading to hepatic encephalopathy. Liver failure or cirrhosis results in the accumulation of neurotoxins, particularly ammonia, which impairs brain function and causes altered mental status. Other frequent causes include renal failure (uremic encephalopathy), hypoglycemia, and sepsis-associated metabolic disturbances.

Do people recover from metabolic encephalopathy?

Yes, recovery is possible, particularly if the underlying cause is identified and treated promptly. Acute metabolic encephalopathy often reverses once metabolic derangements are corrected, such as restoring normal glucose levels, correcting electrolyte imbalances, or managing liver or kidney dysfunction. Delayed intervention may result in permanent brain damage or coma.

What are the main causes of encephalopathy?

Encephalopathy can be caused by:

- Metabolic disturbances – liver failure, renal failure, hypoglycemia, electrolyte imbalances, or metabolic acidosis.

- Toxic exposures – drugs, alcohol, chemotherapy, environmental toxins (toxic metabolic encephalopathies).

- Infections or sepsis – leading to sepsis-associated encephalopathy.

- Hypoxic-ischemic events – reduced oxygen or blood flow to the brain.

- Nutritional deficiencies – e.g., thiamine deficiency causing Wernicke encephalopathy.

What is the difference between toxic encephalopathy and metabolic encephalopathy?

- Toxic encephalopathy is caused by exogenous substances, such as drugs, alcohol, or environmental toxins, directly affecting the brain.

- Metabolic encephalopathy (including acquired metabolic encephalopathies) arises from systemic metabolic disturbances, such as liver or kidney failure, hypoglycemia, or sepsis.

- Both can lead to altered mental status, but toxic encephalopathy typically resolves once the toxin is removed, whereas metabolic encephalopathy requires treatment of the underlying cause.