Community Conceptual Model and the Web of Causation in Epidemiology: Causal Theories of Disease, Germ Theory, and the Web of Causation Model

Effective public health practice depends not only on understanding what causes disease but how and why. For nursing students, grasping models that reveal the interplay of multiple causes is essential to advancing preventive and promotive strategies in health care. Among these, the Community Conceptual Model and the Web of Causation stand out: they shift focus from single, isolated causes to complex, interacting systems that shape health outcomes.

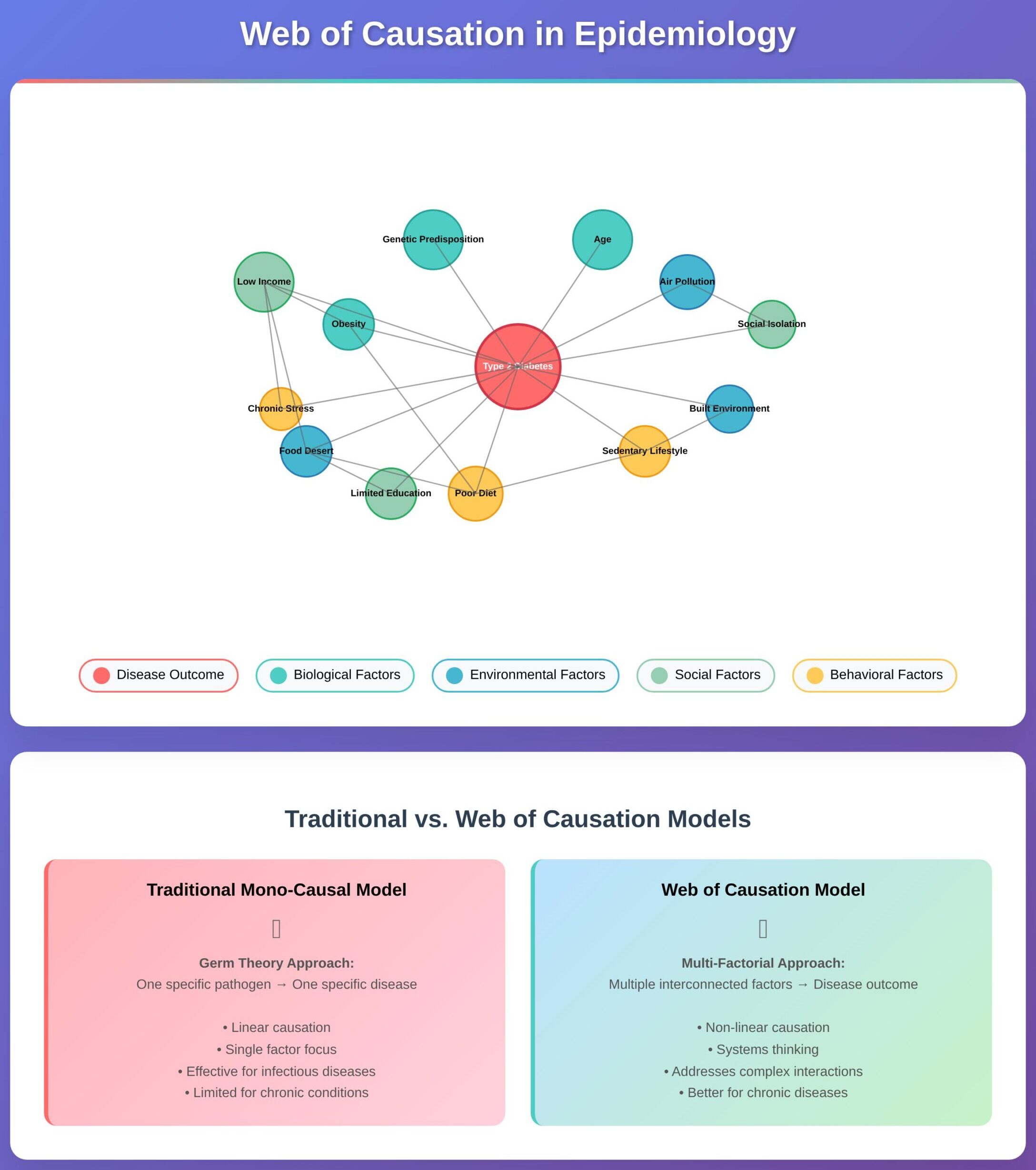

The Web of Causation is a framework used in epidemiology that illustrates how disease causation is rarely due to a single causal factor. Instead, it emphasizes causal pathways, chains of causation, and multiple interacting factors—including environmental, social, behavioral, and biological determinants. This model of disease causation moves beyond older, mono-causal theories such as germ theory, integrating an understanding that disease development often involves many factors that contribute over time.

Meanwhile, the Community Conceptual Model expands our lens even further. It places the individual in context—community health infrastructure, social determinants, socioeconomic status, health policy, and public health capacity—all influence risk factors and disease risk. Nurses who work in community health, health promotion, or preventive interventions will find that blending these models helps in designing more nuanced interventions, enhancing disease prevention strategies, and shaping policy that supports healthy populations.

In this guide, we will explore both frameworks—their origins, components, applications, strengths, and limitations. Through concrete examples such as respiratory disease, chronic disease like type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, we’ll see how these models inform effective intervention strategies and community partnerships. As future healthcare professionals, you will learn how to apply causal inference, assess complex interactions, and contribute to community health projects that lead to better health outcomes.

What is the Community Conceptual Model?

The Community Conceptual Model is a framework that illustrates how the many elements within a community—social, economic, environmental, and institutional—interact to influence health. Rather than focusing on a single cause of illness, the model highlights the connections between different determinants and explains how they collectively shape health outcomes. Communities are viewed not just as geographic places but as dynamic systems where people, organizations, policies, and environments interact to affect well-being.

How did the Community Conceptual Model originate?

The model developed from a need to move beyond narrow explanations of disease that focused on one cause, such as infection or genetics. Public health researchers in the late 20th century recognized that improving population health required looking at multiple levels of influence, from individual behaviors to broader social and environmental factors. Early community health programs, such as those addressing cardiovascular disease in rural areas, demonstrated that lasting improvements in health outcomes often came from coordinated efforts involving schools, workplaces, healthcare providers, and local governments. Over time, this evidence informed the creation of conceptual models that could map out the full picture of community health influences.

What are the key components of the Community Conceptual Model?

While models vary depending on the health issue being studied, several common elements appear across most frameworks:

- Defining the community: The first step is to identify the population and context. This might mean a neighborhood, a rural county, or a particular cultural group.

- Determinants of health: The model accounts for a wide range of influences including socioeconomic conditions, environmental factors, health behaviors, cultural practices, and access to services.

- Risk and protective factors: These are specific conditions that either increase the likelihood of illness (such as tobacco use or food insecurity) or protect against it (like strong social support or regular physical activity).

- Intervention points: The model highlights where action can be taken. For example, interventions may include health education programs, policy changes, or improved community infrastructure.

- Community partnerships: Local institutions, organizations, and residents are key players in designing and sustaining solutions. Collaboration ensures that interventions are both relevant and effective.

- Evaluation and feedback: A good model also identifies how outcomes will be measured, ensuring that programs can be adjusted over time to remain effective.

How does the Community Conceptual Model enhance our understanding of health?

his model provides several advantages for students and healthcare professionals:

- Recognizing complexity. Health outcomes are rarely the result of one factor alone. By mapping multiple influences, the model prevents oversimplification and highlights how social determinants and environmental factors interconnect.

- Focusing on prevention. By pointing to upstream factors such as housing, education, or economic stability, the model supports strategies that target the root causes of illness rather than just the symptoms.

- Designing stronger interventions. Connecting risk factors with possible solutions allows communities to implement interventions that are both realistic and sustainable. For instance, improving access to healthy foods and creating safe spaces for physical activity can complement clinical management of chronic diseases.

- Promoting continuous learning. Because these models are often developed with community input, they are flexible and can evolve as new evidence or challenges arise. This makes them particularly useful in tackling long-term issues like type 2 diabetes or coronary heart disease.

Example: Type 2 Diabetes

A community conceptual model for type 2 diabetes might show how low socioeconomic status leads to poor access to healthy foods and fewer opportunities for exercise. These conditions increase risk factors such as unhealthy diet and obesity, which eventually contribute to disease development. An effective intervention could combine municipal policies that make nutritious foods more available, community projects that create safe walking paths, and healthcare provider programs that promote preventive screening. The model ensures that efforts address both immediate behaviors and the broader systems that shape them.

What is the Web of Causation in Epidemiology?

The Web of Causation is a conceptual framework used in epidemiology to explain how diseases and health outcomes result from multiple interacting factors rather than from a single cause. Instead of attributing disease development to one factor contributing in isolation, the model visualizes a network of interconnected influences—biological, behavioral, environmental, and social—that work together to shape disease occurrence.

In this way, the web illustrates that each factor is both a cause and an effect, connected through causal pathways that influence health at different levels. For example, poverty may limit access to nutritious foods, which increases obesity, which in turn raises the risk of chronic disease such as type 2 diabetes or coronary heart disease. The web of causation model highlights these complex interactions, helping healthcare professionals understand that preventing disease requires addressing more than one causal factor at a time.

How does the Web of Causation differ from traditional models of disease causation?

Earlier models of disease causation, especially the germ theory developed in the 19th century, were mono-causal. Germ theory proposed that each specific disease could be traced back to a single pathogen, and controlling that pathogen would prevent the disease. While revolutionary in understanding infectious diseases, this model was limited when applied to non-infectious conditions such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, or type 2 diabetes, where multiple factors that contribute cannot be explained by one agent.

The Web of Causation differs by recognizing that:

- Causal relationships are not linear. Disease development results from multiple causal pathways that interconnect, rather than a straight line from one pathogen to illness.

- Environmental factors and social determinants play an equal role alongside biological causes. For example, air pollution, smoking, and occupational hazards all link into the web of respiratory disease.

- Causal inference requires complexity. Rather than isolating one direct causal link, epidemiologists analyze a system of interwoven influences, acknowledging that focusing on a single factor may overlook deeper issues.

In practice, this means that while germ theory is still central in explaining infectious disease transmission, the web model better represents infectious and non-infectious health problems shaped by social factors, socioeconomic status, and environmental health conditions.

What are the implications of the Web of Causation for public health interventions?

Because the web model recognizes multiple interacting factors, it underscores that public health strategies must target several levels at once. This approach helps to prevent disease more effectively than interventions focusing on a single cause.

Key implications include:

- Comprehensive interventions. Effective action requires integrating medical care, preventive interventions, and community-based strategies. For example, addressing coronary heart disease involves more than prescribing medication; it may include community health projects that improve access to healthy foods, promote physical activity, and strengthen smoking cessation programs.

- Targeting upstream determinants. By visualizing social determinants of health within the web, public health teams can focus on root causes like housing conditions, education, or employment opportunities. Improving these determinants helps reduce long-term disease risk.

- Designing interventions across sectors. Since the web model shows how different systems interconnect, solutions often require community partnerships—for instance, schools, local governments, and healthcare providers collaborating on vaccination campaigns or nutrition programs.

- Flexibility in addressing both infectious and chronic conditions. The same model can be applied to disease outbreaks (like influenza transmission linked to crowding and vaccination rates) or chronic illnesses (such as type 2 diabetes influenced by diet, genetics, and physical factors).

How can the Web of Causation be applied to specific diseases?

The web can be mapped onto nearly any health problem to reveal how factors that influence outcomes interact. A few examples:

- Respiratory Disease (e.g., asthma or COPD): The web might include environmental factors such as air pollution, occupational dust, and secondhand smoke, along with social factors like housing quality and healthcare access. Preventive strategies could involve improving indoor air quality, enforcing clean-air regulations, and strengthening clinical screening in at-risk communities.

- Type 2 Diabetes: A web of causation for diabetes would link socioeconomic status, poor nutrition, sedentary behavior, obesity, genetic predisposition, and psychosocial stress. Interventions might involve community programs promoting physical activity, subsidies for healthier food options, and clinical preventive interventions targeting high-risk groups.

- Coronary Heart Disease: Here the web might include hypertension, high cholesterol, smoking, sedentary lifestyle, stress, and social determinants like access to care or neighborhood safety. Tackling the problem requires a combination of preventive health education, workplace wellness programs, and community health projects that promote active living.

- Infectious Disease Outbreaks: While germs are the initiating factor, the web also highlights factors that can cause disease spread, such as poor sanitation, inadequate vaccination, global travel, and weak health infrastructure. For instance, influenza outbreaks are better understood when both biological and social factors are mapped together.

How do the Community Conceptual Model and the Web of Causation intersect?

The Community Conceptual Model and the Web of Causation are complementary frameworks that, together, give nurses a richer, action-oriented way to understand disease causation and to design effective public health responses. At a conceptual level, the web emphasizes the causal network of influences that lead to a given health outcome, while the community model situates that web inside a specific social and environmental context — the community — showing where systems, policies, and partnerships shape the web itself. When these two perspectives are combined, they create a practical blueprint: the web identifies the causal pathways and multiple factors that lead to illness; the community model identifies local leverage points and the partners needed to act on them.

What are the synergies between these two models?

Synergies between the two models

- From explanation to action. The web of causation clarifies how factors link to disease (for instance, how stress, poor diet, and neighborhood design together increase diabetes risk). The community model translates that explanation into who and what in the local setting can change those factors — municipal policymakers, schools, employers, clinics, or faith groups. This synergy moves theoretical causal mapping into practical intervention planning.

- Multi-level targeting. Both frameworks emphasize that single, isolated actions are rarely sufficient. The web flags proximal and distal causes; the community model organizes interventions by level (upstream policy, midstream community environment, downstream clinical care). Working together, they help teams select complementary strategies that act across levels rather than duplicating effort at just one level.

- Evidence-driven prioritization. The web helps rank risk factors by plausibility and strength of association. The community model adds feasibility and equity filters — for example, whether a potential intervention is politically possible, culturally acceptable, or likely to reduce health inequities. The combined approach leads to higher-value choices.

- Improved evaluation logic. Mapping causal pathways within the community context clarifies which intermediate indicators to measure (e.g., changes in food availability, reductions in air pollutant levels, increases in screening uptake) and which ultimate outcomes to expect. This makes evaluation realistic and useful for iterative improvement.

How can these frameworks be utilized in disease prevention and health promotion strategies?

When designing preventive and health-promotion activities, the combined approach encourages these practical steps:

- Map the causal web for the problem. Start with a clear health outcome (e.g., rising rates of type 2 diabetes). Use the web of causation to lay out biological, behavioral, social, and environmental contributors and how they interact. Include social determinants and socioeconomic drivers in the map so upstream causes aren’t missed.

- Overlay community context. Use the Community Conceptual Model to identify local features that shape the web: existing community programs, governance structures, resource constraints, cultural norms, and key stakeholder organizations. This highlights where community partnerships or community health projects could be mobilized.

- Identify multi-level interventions. Select complementary interventions across levels. For diabetes this could mean: municipal policies to improve food retail, school programs for healthy lunches, community health workers to support behavior change, and clinic-based screening. Combining policy and on-the-ground programs addresses both root causes and immediate risk factors.

- Sequence and integrate. Decide which interventions are prerequisites (e.g., securing funding or passing a zoning change) and which can be launched in parallel (e.g., provider training and community education). Integration prevents fragmented efforts that fail to shift long-term risk.

- Monitor intermediate indicators and adjust. Track both process metrics (policy adoption, program reach) and health proxies (BP control rates, BMI trends). The community model’s feedback loops encourage continuous learning so interventions can be refined.

Example — Asthma (a respiratory example):

- Causal web: indoor allergens, outdoor air pollution, tobacco smoke exposure, housing quality, access to care, and stress.

- Community context: high housing density in a neighborhood, few green spaces, limited clinic hours, and community groups with strong local influence.

- Interventions: housing remediation to remove mold (upstream/environmental), enforcement of clean-air regulations (policy), school-based asthma education and medication management (midstream), and clinic outreach for preventive inhaler prescriptions (downstream). Combining these reduces triggers and strengthens management — an integrated approach that the two models naturally recommend.

Example — Coronary Heart Disease:

- Causal web: hypertension, cholesterol, smoking, poor diet, physical inactivity, psychosocial stress, and neighborhood walkability.

- Community actions informed by the models: public smoking bans, workplace wellness incentives, safer sidewalks and bike lanes, community screening for hypertension, and food policy that improves healthy-food access. This coordinated package acts on several causal pathways simultaneously.

In what ways do these models inform policy-making in public health?

- Clarifying the policy target. Policy makers often ask “What should we change?” The combined models provide a clear answer: change upstream determinants that the causal web shows feed downstream risk. This gives a rational basis for policies that might otherwise seem indirect (e.g., housing codes to reduce asthma rather than only funding inhaler access).

- Building the case for cross-sector policy. Since causal webs span sectors (transportation, housing, education, healthcare), the community model demonstrates why health in all policies is necessary. It clarifies co-benefits (e.g., better sidewalks improve physical activity and reduce social isolation) that strengthen policy arguments.

- Prioritizing and sequencing policy interventions. The models help policy makers identify high-leverage actions (those likely to change many downstream risk factors) and assess feasibility and equity implications before committing resources.

- Economic and ethical framing. By linking causes to long-term outcomes, the combined framework supports economic analyses (costs averted from prevented disease) and equity arguments (policies that reduce socioeconomic gradients will likely reduce health disparities).

- Accountability and evaluation for policy. Mapping causal pathways sets measurable expectations for policies — what intermediate indicators should change and in what timeframe — enabling transparent evaluation and policy refinement.

Policy example: A city facing rising rates of diabetes and childhood obesity can use the two frameworks to justify a package that includes a sugar-sweetened beverage tax (policy), subsidies for fruit and vegetable vendors (environmental/market), and school nutrition standards (institutional). The models help explain why single measures (e.g., only nutrition education) are unlikely to succeed and why a policy package is more defensible.

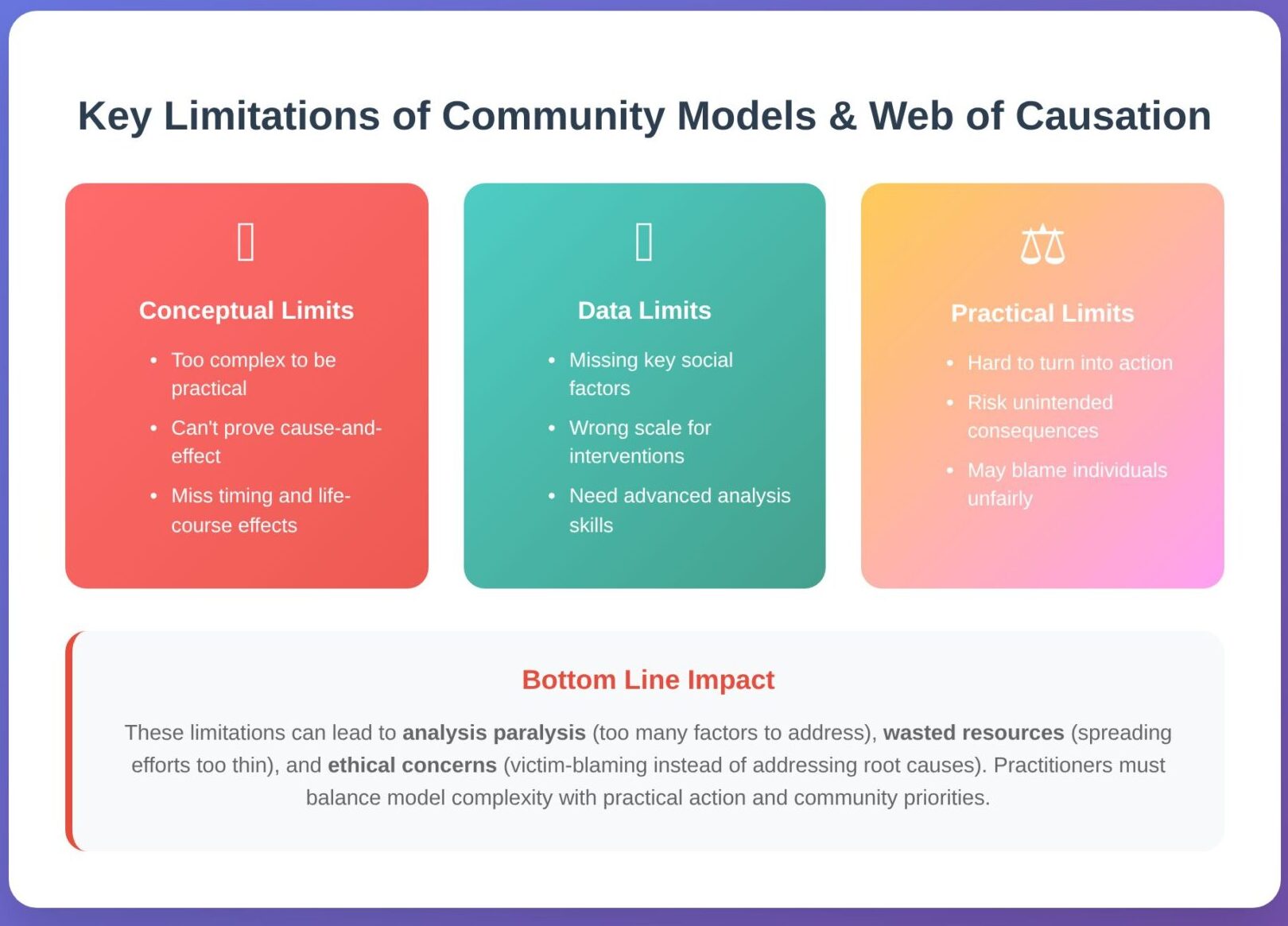

What are the limitations of the Community Conceptual Model and the Web of Causation?

Both the Community Conceptual Model and the Web of Causation are valuable for organizing how we think about health and illness, but they are not perfect. Understanding their limits is essential so nursing students and practitioners can apply the frameworks carefully and responsibly.

Conceptual and theoretical limits

- Complexity versus usability. Detailed maps of influences can become so dense that they stop being practical. When everything appears relevant, teams may struggle to prioritize where to act, which undermines the model’s usefulness for planning real-world projects.

- Proving cause-and-effect. Observational and cross-sectional community data frequently show associations but do not prove that one factor produces another. Without robust study designs, long-term data, or analytic methods that address confounding, it is difficult to identify direct cause-and-effect links that would justify major policy changes.

- Timing and cumulative exposure. Some drivers operate across decades; models that ignore timing (life stages or cumulative exposures) can miss how early disadvantage leads to later illness, or how short-term changes may not immediately alter long-term risk.

Measurement and data limits

- Gaps in available data. Key determinants such as informal social networks, local norms, or housing microconditions are often absent from routine datasets. Poor or missing measurements make parts of the model speculative rather than evidence-based.

- Scale mismatch. Drivers act at different levels—individual, household, neighborhood, system—and data sources do not always align with the level where interventions are expected to work. Aggregating data improperly can hide important local patterns.

- Analytic demands. Evaluating a network of interrelated influences often requires advanced methods (multilevel models, structural equation modeling, simulations). Smaller teams or resource-limited settings may lack the expertise needed to perform these analyses rigorously.

Practical and ethical constraints

- Translating maps into action. Identifying many upstream drivers can leave communities unsure where to begin. Political will, funding cycles, and institutional priorities often limit the ability to implement system-level solutions, even when the model makes the case for them.

- Unintended consequences. Actions focused on one node in a system can shift risks elsewhere. For instance, densifying housing without addressing ventilation or green space can increase respiratory problems for some residents. Good planning anticipates such trade-offs.

- Stigmatization and fairness. Emphasizing behaviors or social contributors risks blaming individuals rather than addressing structural causes. Ethical application requires centering equity, avoiding victim-blaming language, and ensuring benefits reach those most affected.

What challenges do researchers face when applying these models?

- Choosing what to include. Deciding which factors to show — and which to omit — shapes priorities. Selection bias or limited stakeholder input can produce models that reflect researchers’ assumptions more than community reality.

- Confounding and ambiguous pathways. Disentangling mediators, confounders, and modifiers needs explicit assumptions and careful analysis. Visual tools that make assumptions explicit can help but are underused in many projects.

- Interdisciplinary and cross-sector work. The models often span transport, housing, education, and health—requiring partnerships across disciplines. Building and sustaining these collaborations takes time, trust, and resources.

- Funding and time horizons. Policy-level outcomes often require long timelines to observe; short-term grants and performance cycles can incentivize small projects over systemic change.

- Community engagement and representation. Authentic partnership with residents improves model relevance but raises questions about whose perspectives are included, how priorities are set, and who benefits.

How do cultural, social, and economic factors influence these models?

Cultural norms, social structures, and economic systems both form the content of the model and influence whether proposed solutions will work. Examples include:

- Local beliefs and program uptake. Cultural understandings of illness, historical mistrust, or stigma can limit uptake of preventive programs (for example, vaccine hesitancy rooted in community experience).

- Social networks. Strong social ties can protect health, but close networks that normalize harmful practices (e.g., high tobacco use) can sustain risk across generations.

- Economic constraints. Poverty constrains choices: housing, employment conditions, and food access all influence exposures and the feasibility of recommended changes. Interventions that ignore affordability or access are unlikely to succeed.

- Structural inequities. Systems of power—based on race, class, gender, or other axes—shape who is exposed, who can respond to programs, and who is prioritized in policy decisions. Models that overlook these structures will miss the root drivers of disparities.

Are there alternative models that address the shortcomings of these frameworks?

Several frameworks and analytic tools help compensate for the limits described above:

- Socio-ecological frameworks. These layer influences from individual to policy level, making multi-level intervention planning easier to communicate and implement.

- Lifecourse approaches. Emphasize timing, critical windows, and cumulative exposure—valuable for chronic disease prevention and for understanding long latency effects.

- Systems science (system dynamics, agent-based simulation). These methods model feedback loops, delays, and non-linear responses, and they allow teams to simulate interventions and detect unintended consequences before scale-up (for example, virtual testing of obesity policy packages).

- Syndemics frameworks. Focus on interacting epidemics (e.g., substance use and infectious disease) and prioritize structural disadvantage and co-occurring risks.

- Causal-inference tools (DAGs and related methods). Make analytic assumptions explicit and guide study design and adjustment strategies to reduce bias in observational research.

- One Health and ecological perspectives. For diseases that link humans, animals, and environments (zoonoses), these approaches capture cross-species and ecological drivers that a simple community map might miss.

Conclusion

The Community Conceptual Model and the Web of Causation together offer a robust lens for understanding how disease develops and how it can be prevented. While traditional models, such as the germ theory or the simple triad of agent–host–environment, highlighted important insights, they often relied on a single cause perspective. Today’s complex health challenges — from chronic disease like coronary heart disease and type 2 diabetes, to emerging respiratory and infectious conditions — demand frameworks that acknowledge the multiple factors and complex interactions shaping health.

The Web of Causation provides a way to map causal pathways and identify the factors that contribute disease causation. The Community Conceptual Model situates these webs within the realities of community health, where social determinants of health, socioeconomic status, and environmental factors determine whether interventions succeed or fail. Used together, they encourage healthcare professionals to design preventive strategies that interconnect policy, systems, and individual care.

Of course, both frameworks have limits. Their very strength — embracing complexity — can make them difficult to translate into immediate action. Data gaps, cultural differences, and competing priorities challenge researchers and policymakers alike. Yet acknowledging these limitations has also spurred innovation: new approaches in epidemiology, systems thinking, and interdisciplinary research are developing more dynamic ways to model the disease process.

For nursing students, the key lesson is clear. These frameworks are not abstract theories confined to textbooks; they are practical guides for addressing disease prevention and health promotion in real communities. Whether leading community health projects, advocating for preventive interventions, or collaborating across sectors, nurses who understand these models can help lead a culture of excellence in healthcare. By applying the insights of the Community Conceptual Model and the Web of Causation, future practitioners can move beyond focusing on a single causal factor and instead engage the multiple interacting factors that truly shape health outcomes.

Ultimately, the integration of these models reminds us that preventing disease and promoting wellness is not about isolating one factor, but about recognizing the complex causal systems that define human health. In doing so, nurses and other healthcare providers can better anticipate challenges, build stronger community partnerships, and contribute to lasting improvements in public health.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the web of causation model in epidemiology?

The web of causation model explains that diseases usually arise from multiple interacting factors rather than a single cause. It highlights the causal pathways linking biological, social, behavioral, and environmental influences, showing how they interconnect to shape disease occurrence.

What are the theories of disease causation in epidemiology?

Theories of disease causation include the germ theory (disease caused by specific pathogens), the epidemiologic triad (agent–host–environment), multiple causation theory (disease results from many interacting factors), and modern frameworks like the web of causation, which emphasize complexity and context.

What is the web of causation theories?

Web of causation theories refer to conceptual frameworks that show how factors that can cause disease are linked in a network. They argue against focusing on a single causal factor and instead stress that complex interactions across levels — from genetics to social determinants — drive disease development.

What is the concept of epidemiology in the community?

Epidemiology in the community is the study of how diseases and health outcomes are distributed among populations and the factors that influence them. It emphasizes community health, public health interventions, and understanding determinants of health like environment, socioeconomic status, and cultural practices to improve population well-being.