Disability Research Topics: Exploring Disability Studies, Nursing Assessments, and Essay Examples for People with Disabilities

Disability research occupies a critical space at the intersection of health sciences, social policy, and human rights. It seeks to deepen our understanding of the diverse experiences of individuals with disabilities, ranging from physical and sensory impairments to intellectual and developmental conditions. Much like nursing assessments provide a systematic approach to evaluating patient needs, disability research offers a structured framework for exploring how disability shapes health, education, employment, and social participation.

At its foundation, this field is not limited to clinical or diagnostic categories. Instead, it engages with broader questions about accessibility, social inclusion, and equity, while also highlighting the lived experiences of disabled individuals across different contexts. By integrating perspectives from nursing, rehabilitation, sociology, psychology, and education, disability research extends beyond describing impairments—it examines how environments, policies, and attitudes influence opportunities and quality of life.

Recent scholarship underscores the growing importance of interdisciplinary approaches in disability studies. Advances in assistive technologies, shifts in policy frameworks such as the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, and evolving models of disability have reshaped how researchers frame their investigations. Additionally, global challenges such as the COVID-19 pandemic have exposed persistent barriers to access, reinforcing the urgency of research that addresses both immediate health concerns and long-term structural inequalities.

This guide introduces key themes and directions in disability research, from conceptual foundations and methodological approaches to the impact of social determinants and technological change. It highlights the central role of nursing and physical assessment in understanding functional needs, while also situating these practices within wider social and policy contexts. Whether the focus is on children with developmental challenges, older adults navigating physical disabilities, or students requiring inclusive education, disability research provides the evidence base necessary for promoting equity and advancing rights.

Ultimately, disability research is not only about documenting barriers but also about identifying solutions that foster participation, inclusion, and dignity. By examining diverse disability research topics and integrating insights from nursing assessments, this work contributes to a more holistic understanding of health and social well-being for people with disabilities.

What Are Disability Research Topics?

Disability research topics are the specific questions, problems, and domains that scholars, clinicians, and policymakers investigate to understand the lived experience, causes, measurements, interventions, and outcomes related to functional differences and impairments. These topics span multiple levels — from individual clinical assessment and rehabilitation to population-level surveillance, policy evaluation, and rights-based implementation. In practice they often group into thematic clusters such as functional assessment and measurement, health and rehabilitation outcomes, accessibility and environment, education and inclusive services, employment and economic participation, assistive technology adoption, stigma and social inclusion, and legal/policy implementation.

For nursing and physical assessment specifically, common research topics include: the reliability and validity of assessment tools that measure activities of daily living (ADLs) and participation, the utility of the ICF (International Classification of Functioning) framework in care planning, outcomes of nurse-led rehabilitation programs, and barriers to delivering person-centred care in community or acute settings. These practical topics bridge bedside assessment with larger systemic questions about access and equity.

How Do We Define Disability in Research?

Definitions matter because they determine who is counted, which outcomes are measured, and how services are designed. Modern international practice commonly uses the WHO’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), which frames disability as a dynamic interaction between a person’s health condition, their activity limitations and participation restrictions, and environmental and personal factors. That is, disability is not treated solely as a medical label but as a description of functioning within context. Using the ICF shifts emphasis from diagnosis to what people can do (function) and what barriers or supports shape participation.

National public-health definitions — for example those used by the CDC — operationalize disability for surveillance by describing impairments that limit activities (vision, hearing, mobility, cognition, communication, mental health, and self-care), which helps researchers design surveys and estimate prevalence. This dual use of conceptual (ICF) and operational (survey-oriented) definitions is common in disability research and underscores why careful choice of measurement matters for comparability across studies.

Legal and rights frameworks — most notably the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) — also influence definitions used in research by centring equality, non-discrimination and accessibility. The CRPD encourages researchers to think beyond impairment to the social and policy barriers that create disability in practice.

Why Is Disability Research Important?

There are three closely linked reasons why disability research is essential:

- Magnitude and unmet needs. The WHO/World Bank World Report estimated that over one billion people live with significant functional limitations globally; that scale means disability is a major public-health and development concern that intersects with education, employment, and poverty. High-quality research documents needs and tests solutions.

- Policy and service design. Research provides the evidence base for policies (e.g., accessibility standards, rehabilitation funding, inclusive education), for evaluating the impact of legal instruments like the CRPD, and for tailoring clinical pathways that improve quality of life. Commentary on the World Report highlights how research can guide policy priorities and resource allocation.

- Health equity and clinical outcomes. People who experience functional limitations are more likely to encounter healthcare disparities, poorer mental-health outcomes, and barriers to preventive care. Nursing and allied-health research — for example on assessment tools and care models — can reduce these gaps by improving early identification, care planning, and continuity of services.

What Are the Different Types of Disabilities to Consider?

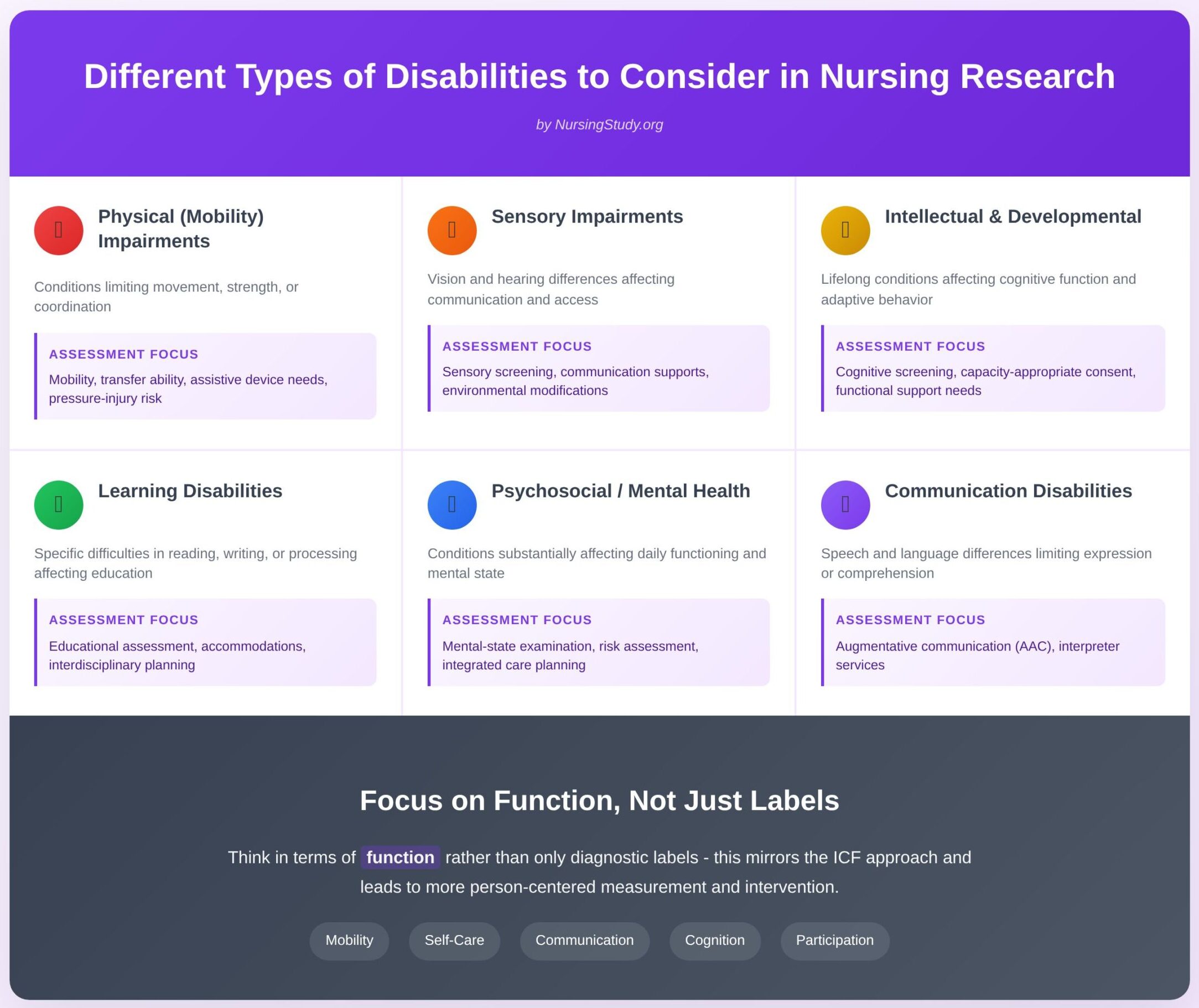

Disability is heterogeneous. Research and assessment typically consider several major categories (these categories often overlap and a single person may have multiple needs):

- Physical (mobility) impairments: conditions that limit movement, strength, or coordination (e.g., spinal cord injury, limb loss). Assessment emphasis: mobility, transfer ability, assistive device needs, pressure-injury risk.

- Sensory impairments: vision and hearing differences that affect communication and environmental access. Assessment emphasis: sensory screening, communication supports, environmental modifications.

- Intellectual and developmental disabilities: lifelong conditions affecting cognitive function and adaptive behaviour (including some people described as having intellectual disabilities or developmental delay). Assessment emphasis: cognitive screening, capacity-appropriate consent processes, functional support needs.

- Learning disabilities: specific difficulties in reading, writing, calculus, or processing that affect educational participation (often requiring adapted instruction or assistive tech). Assessment emphasis: educational assessment, accommodations, interdisciplinary planning.

- Psychosocial / mental-health disabilities: conditions such as major depression, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder that substantially affect daily functioning. Assessment emphasis: mental-state examination, risk assessment, integrated care planning.

- Communication disabilities: speech and language differences that limit expression or comprehension; assessment focuses on augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) and interpreter services.

For nursing and physical assessment research, it is useful to think in terms of function (mobility, self-care, communication, cognition, participation) rather than only diagnostic labels — this mirrors the ICF approach and leads to more person-centred measurement and intervention.

300 Disability Research Topics for Nursing Students

Physical (Mobility) Impairments

- Rehabilitation outcomes in spinal cord injury

- Fall prevention strategies for older adults with mobility loss

- Pressure injury prevention in wheelchair users

- Prosthetic technology adoption and quality of life

- Exercise interventions for individuals with limb loss

- Barriers to community participation among people with mobility impairments

- Nursing assessment tools for gait and transfer ability

- Occupational therapy effectiveness for mobility limitations

- Home modifications and fall reduction outcomes

- Physical activity programs in schools for children with cerebral palsy

- Access to public transportation for wheelchair users

- Rural healthcare access for individuals with mobility impairments

- Return-to-work programs after spinal cord injury

- Pain management strategies in mobility-impaired populations

- Long-term outcomes of hip replacement in older adults

- Role of physiotherapy in stroke rehabilitation

- Technology-assisted mobility training

- Environmental barriers to exercise for people with mobility impairments

- Adaptive sports participation and psychological well-being

- Nurse-led rehabilitation models for mobility disabilities

- Caregiver burden in families of physically disabled children

- Gender differences in rehabilitation outcomes

- Policy impact of the Americans with Disabilities Act on mobility access

- Vocational rehabilitation for adults with mobility impairments

- Role of robotics in gait training

- Chronic pain and disability management strategies

- Community-based physical activity programs

- Barriers to equal access in healthcare for mobility-impaired populations

- Hospital readmissions among patients with spinal cord injuries

- Wheelchair accessibility in urban infrastructure

- Mobility impairments and cardiovascular health risks

- Relationship between obesity and mobility limitations

- Patient-reported outcomes in orthopedic rehabilitation

- Falls in long-term care facilities

- Adaptive equipment training effectiveness

- Experiences of disabled veterans with prosthetics

- Cultural perspectives on mobility impairments

- Telehealth in rehabilitation services

- Mobility and participation in rural vs. urban settings

- Accessibility of fitness facilities

- Nurse education in physical disability assessment

- Impact of mobility impairments on family dynamics

- Employment barriers for people with mobility impairments

- Long-term effects of mobility impairment on mental health

- Peer support programs in rehabilitation

- Physical therapy adherence among older adults

- Resilience in people with chronic mobility conditions

- Integration of assistive devices in school programs

- Quality of life after amputation

- Ethical considerations in prosthetic development

Sensory Impairments

- Early detection of hearing loss in newborns

- Classroom accommodations for visually impaired students

- Braille literacy and academic outcomes

- Accessibility of digital health records for blind users

- Use of hearing aids in older adults

- Employment barriers for people with sensory impairments

- Quality of life in cochlear implant users

- Nursing assessments for sensory loss in older adults

- Assistive technologies for vision impairment

- Accessibility of emergency alerts for deaf populations

- Inclusive education strategies for blind students

- Mental health in people with sensory impairments

- Rehabilitation programs for dual sensory loss

- Communication strategies with deaf patients in hospitals

- Role of interpreters in healthcare settings

- Accessibility of online learning for visually impaired students

- Aging and progressive vision loss

- Social isolation in people with hearing impairments

- Orientation and mobility training outcomes

- Impact of sensory impairments on family relationships

- Literacy outcomes in children with hearing loss

- Accessibility of cultural events for sensory-impaired individuals

- Sensory impairments and stigma in society

- Sign language inclusion in schools

- Barriers to accessing audiology services

- Vision rehabilitation programs

- Health disparities among people with sensory impairments

- Screen-reader accessibility of health websites

- Inclusive workplace accommodations for sensory impairments

- Dual disability: sensory impairment and intellectual disability

- Impact of hearing loss on language development

- Accessibility of voting for visually impaired people

- Assistive apps for blind users

- Global disparities in vision care access

- Parent support programs for children with hearing loss

- Integration of sensory impairment education in nursing curricula

- Experiences of women with vision loss

- Cultural attitudes towards deafness

- Inclusive recreational programs for blind youth

- Effectiveness of captioning services in higher education

- Communication barriers in acute care settings

- Telehealth accessibility for sensory-impaired populations

- Adaptive sports for blind athletes

- Impact of vision impairment on driving independence

- Employment outcomes in deaf professionals

- Inclusive disaster preparedness planning

- Barriers to higher education for sensory-impaired students

- Religious participation among visually impaired individuals

- Experiences of stigma among people with hearing impairments

- Future directions in sensory prosthetics

Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

- Inclusive education programs for children with intellectual disabilities

- Transition planning for youth with developmental disabilities

- Health disparities in adults with intellectual disabilities

- Communication strategies in nursing care

- Stigma and discrimination faced by individuals with intellectual disabilities

- Employment opportunities for adults with developmental disabilities

- Family stress and coping strategies

- Access to mental health services

- Community inclusion initiatives

- Adaptive behavior assessment tools

- Legal rights and guardianship issues

- Role of nurses in developmental screening

- Technology-assisted learning for children with intellectual disabilities

- Social skills training interventions

- Barriers to healthcare access

- Sexual health education for people with developmental disabilities

- Safety training programs

- Person-centred care planning

- Early childhood intervention outcomes

- Transition to adulthood challenges

- Advocacy by families of individuals with intellectual disabilities

- Experiences of disabled adults in higher education

- Inclusive housing models

- Physical health disparities in developmental disability populations

- Attitudes towards people with intellectual disabilities

- Long-term care options

- Participation in sports and recreation

- Cognitive assessment tools validation

- Peer support programs

- Autism spectrum disorders and social inclusion

- Co-occurring physical and developmental disabilities

- Communication support strategies

- Use of ICF framework in assessment

- Policy impact of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

- Inclusive employment practices

- Special education teaching strategies

- Barriers to transition from school to work

- Mental health co-morbidities

- Nurses’ attitudes toward caring for individuals with developmental disabilities

- Gender disparities in access to services

- Parents’ perspectives on inclusive education

- Longitudinal health outcomes

- Experiences of women with intellectual disabilities

- Inclusive recreation programs

- Early detection of developmental delays

- Nutrition interventions

- Role of community health workers

- Ethical considerations in research participation

- Telehealth use in intellectual disability services

- Cross-cultural perspectives on developmental disabilities

Learning Disabilities

- Academic outcomes of students with dyslexia

- Reading interventions in early childhood

- Teacher training in learning disability awareness

- Use of assistive technology in classrooms

- Self-esteem in students with learning disabilities

- Inclusive classroom models

- Parental involvement in education programs

- Access to higher education for students with learning disabilities

- Stigma in school environments

- Coping strategies of learners with disabilities

- Accommodations in standardized testing

- College transition programs

- Peer mentoring effectiveness

- Impact of early diagnosis

- Gender differences in learning disability identification

- Learning disabilities and mental health

- Social inclusion of learners with disabilities

- Barriers to equal access in education

- Strategies for math learning disabilities

- Use of speech-to-text technology

- Teacher attitudes towards learning disabilities

- Policy implementation in special education

- Reading comprehension interventions

- Experiences of disabled individuals in online learning

- Curriculum adaptation effectiveness

- Literacy outcomes with phonics-based interventions

- Universal design for learning approaches

- Parental stress and coping strategies

- Learning disability identification in multicultural settings

- Experiences of students with learning disabilities in higher education

- Role of school nurses in supporting learners

- Early childhood screening programs

- Collaboration between educators and parents

- Long-term employment outcomes

- Social skills training effectiveness

- Impact of inclusion on peer relationships

- Advocacy programs for students with learning disabilities

- Teacher perceptions of inclusive education

- Experiences of learners without disabilities in inclusive classrooms

- Role of assistive apps in literacy development

- Transition to independent living

- Dropout rates among students with learning disabilities

- Resilience in learners with disabilities

- Special education teacher workload and burnout

- Parental satisfaction with school support services

- Classroom behavior management strategies

- Early intervention policy outcomes

- International comparisons of special education

- Development of individualized education programs (IEPs)

- Learners’ experiences of stigma in peer groups

Psychosocial / Mental-Health Disabilities

- Barriers to mental healthcare access

- Stigma surrounding schizophrenia

- Peer-support programs for depression

- Community integration for people with bipolar disorder

- Housing programs for individuals with psychosocial disabilities

- Role of nurses in suicide prevention

- Workplace accommodations for employees with mental health conditions

- Psychosocial disabilities and poverty

- Co-morbidity of mental health and substance use

- Mental health literacy campaigns

- Cultural perceptions of psychosocial disabilities

- Caregiver stress in families

- Telepsychiatry interventions

- Mental health services for refugees

- Recovery-oriented nursing care

- Supported employment programs

- Role of spirituality in recovery

- Long-term medication adherence

- Mental health and homelessness

- Barriers to education for young adults with psychosocial disabilities

- Early intervention in psychosis

- Global disparities in mental health services

- Policy impacts on mental health care access

- Community stigma reduction campaigns

- Role of peer specialists in recovery

- Nursing assessment tools for psychosocial functioning

- Legal issues in involuntary treatment

- Mental health crisis intervention models

- COVID-19 and psychosocial disability impacts

- Integration of mental and physical healthcare

- Barriers to equal access in primary care

- Gender-specific experiences of psychosocial disabilities

- Intersectionality and mental health

- Outcomes of cognitive-behavioral interventions

- Mental health of older adults

- Suicide prevention in schools

- Stigma in healthcare settings

- Role of nurses in mental health promotion

- Supported housing models

- Adolescent mental health programs

- Quality of life outcomes

- Experiences of disabled individuals with psychosocial disabilities

- Experiences of stigma and discrimination

- Patient narratives in mental health research

- Family-centred interventions

- Ethical concerns in psychiatric research

- Telehealth outcomes for psychosocial disabilities

- Resilience in people with serious mental illness

- Role of community health workers

- Integration of psychosocial disability into disability rights policy

Communication Disabilities

- Effectiveness of speech therapy interventions

- Early detection of speech and language delays

- Use of augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) devices

- Family involvement in communication interventions

- Barriers to accessing speech-language therapy

- Inclusive classroom strategies

- Social outcomes of AAC use

- Teacher attitudes towards students with communication disabilities

- Literacy outcomes in children with speech delays

- Telepractice in speech-language pathology

- Nurse training in communication disorders

- Role of interpreters in healthcare settings

- Cultural perceptions of communication disabilities

- Parent stress in raising children with speech impairments

- Early childhood screening effectiveness

- Peer acceptance of children with speech differences

- Communication barriers in emergency care

- Employment outcomes for adults with communication disabilities

- Accessibility of legal processes

- AAC in higher education

- Technology adoption in speech therapy

- Role of speech therapy in autism spectrum disorders

- Inclusive recreation programs

- Bilingualism and communication disabilities

- Stigma experiences among children with communication disorders

- Nurse–patient communication challenges

- Efficacy of group speech therapy

- Teacher collaboration with speech-language pathologists

- Policy support for communication services

- Impact on family relationships

- Transition to adulthood for AAC users

- Communication disabilities and mental health outcomes

- Experiences of students with speech disorders in inclusive classrooms

- Access to AAC in low-income countries

- Development of user-friendly AAC apps

- Quality of life for AAC users

- Communication barriers in long-term care settings

- Speech-language therapy in rural areas

- Integration of communication disability education in nursing curricula

- Ethical issues in AAC use

- Gender perspectives in communication disabilities

- Experiences of older adults with communication impairments

- Patient safety and communication barriers

- Augmented reality tools in speech therapy

- Communication disabilities and equal access in healthcare

- Narratives of people with communication impairments

- Peer mentoring in speech therapy

- Accessibility of online learning for communication-impaired students

- Teacher stress in managing communication disorders

- Advocacy and rights for people with communication disabilities

What Are the Current Trends in Disability Research?

Disability research has shifted markedly over the last decade from narrow clinical descriptions toward broader, interdisciplinary questions about participation, equity, and systems of support. Researchers increasingly examine functional outcomes (what people can do in their environments) rather than only diagnostic labels, and they prioritize questions that connect health, education, employment, and civil rights. Major, recurring trends include:

- Technology, data and small-scale innovation. There is rapid growth in research on digital assistive tools, wearables, AI-enabled prosthetics and “small-data” machine-learning approaches tailored to individual users. Funded programs and policy reports emphasize technology that supports independence (smart wheelchairs, exoskeletons, speech-to-text for classrooms) while also noting affordability and inclusion challenges. These developments are reshaping both interventions and study designs (feasibility trials, usability studies, participatory co-design).

- Interdisciplinarity and systems thinking. Studies now routinely combine nursing, rehabilitation, engineering, education, public health and policy analysis. That means trial outcomes are being linked to environmental and social variables (housing, transport, workplace practices) rather than being reported in isolation — a necessary step if research aims to improve everyday participation. Global policy and inclusion reports promote this systems focus in research agendas.

- Methodological pluralism and “small-data” approaches. As individualized assistive solutions proliferate, researchers are adopting mixed-methods and n-of-1 designs, human-centred evaluation, and rapid iterative testing in real-world settings. This trend supports more pragmatic, person-centred evidence that is directly relevant to clinicians and community providers.

- Rights-based and policy-oriented evaluation. Researchers are increasingly asked to evaluate the implementation and impact of laws, strategies for inclusion, and international frameworks that underpin rights. Work that links legal/policy change to measurable outcomes (access to services, educational attainment, employment rates) is on the rise.

- Attention to equity, intersectionality and decolonizing perspectives. Studies are moving beyond single-axis analyses (e.g., disability alone) to explore how disability intersects with race, gender, indigeneity, socioeconomic status, sexuality and geography — and how these intersections shape access, stigma and outcomes. Parallel conversations about decolonizing the field and centring Global South perspectives are changing who sets research questions, who participates, and which knowledge counts.

- Post-pandemic service-delivery research (telehealth, workforce, preparedness). COVID-19 sharpened attention on remote care, continuity of home services, and the structural barriers that amplify disadvantage during crises. Research now examines which telehealth models improved access and which left some groups behind — with implications for nursing practice, care coordination and emergency planning.

How Are Technological Advances Impacting Disability Research?

Technology is both accelerating new lines of inquiry and raising critical questions for researchers and clinicians.

- New interventions and metrics. AI, wearables and sensor technology generate continuous, objective data (gait patterns, activity levels, pressure points) that enable finer measurement of function and earlier detection of deterioration. This expands research from point-in-time assessments to longitudinal monitoring and predictive models — promising improvements in prevention (e.g., pressure injury risk) and personalised rehabilitation.

- Co-design and participatory development. High-impact studies emphasize user involvement at all stages: design, testing, and evaluation. When people who will use the device are included, adoption, satisfaction and outcomes improve; when they are excluded, technologies fail to meet real needs and widen inequities. Recent journalism and policy reviews show both the promise of advanced prosthetics and the persistent problem of unaffordability and low user involvement.

- Educational and assessment tools. AI and adaptive software (e.g., reading supports, speech recognition) are reshaping educational research: classroom trials now test whether such tools improve attainment for learners with specific needs, and whether nurses and school health staff can reliably integrate them into screening and referrals. There are promising findings but also warnings about over-reliance and equity of access.

- Ethics, privacy, and accessibility. The flood of personal health data raises ethics and governance questions: who owns sensor data, how is it shared, how do we prevent bias in ML models, and how do we ensure accessibility of the tech itself? These questions are increasingly central to research proposals and funding decisions.

What Role Does Intersectionality Play in Disability Studies?

Intersectionality is no longer an optional lens; it is mainstreaming into theory, methods and interpretation:

- Why it matters. Intersectional analysis uncovers how overlapping identities compound disadvantage (for example, how gender and poverty shape the experience of impaired mobility or how race and disability affect diagnostic pathways). Research that ignores these intersections risks producing incomplete or misleading recommendations.

- Methodological consequences. Intersectional work encourages mixed methods, purposive sampling to include multiply-marginalized groups, and analytic strategies that test interactions rather than only main effects. It also prompts ethical reflexivity: who is leading research, who benefits, and whether study instruments are culturally valid.

- Examples: empirical projects now compare outcomes for women with disabilities across income brackets and ethnic groups, evaluate how LGBTQ+ status interacts with access to community supports, and study how rurality compounds service gaps — all with the aim of producing targeted, equity-focused interventions.

How Is Disability Research Addressing Social Justice Issues?

Work focused on social justice reframes the purpose of research: not only to treat impairment, but to dismantle barriers and advance rights.

- Rights-centred evaluation. Evaluations of policies (for example, national inclusion strategies or specific implementation of CRPD commitments) measure whether legal protections translate into real changes in access, education, or employment. Global inclusion reports and national monitoring increasingly demand rigorous evidence on impact.

- Decolonizing and participatory agendas. Scholarship calling for decolonized disability studies urges funders and institutions to centre Indigenous, Global South and community knowledge, use participatory methods, and avoid extractive research practices. This is reshaping whose voices inform interventions and what success looks like.

- From documentation to advocacy. Researchers are partnering with advocacy groups and service users to translate findings into policy briefs, litigation, workplace guidance and education reforms — turning evidence into actionable change on access, reasonable accommodations, and anti-discrimination measures. Employer-facing literature also documents the business case for inclusion, informing corporate practice and research uptake.

- Pandemic lessons = everyday policy experiments. Many of the temporary shifts during COVID-19 (remote work, flexible schooling, broader telehealth) serve as real-world experiments in inclusion. Disability-focused research is now evaluating which pandemic-era adaptations should be retained to improve equity permanently.

What Are Key Areas of Focus in Disability Research?

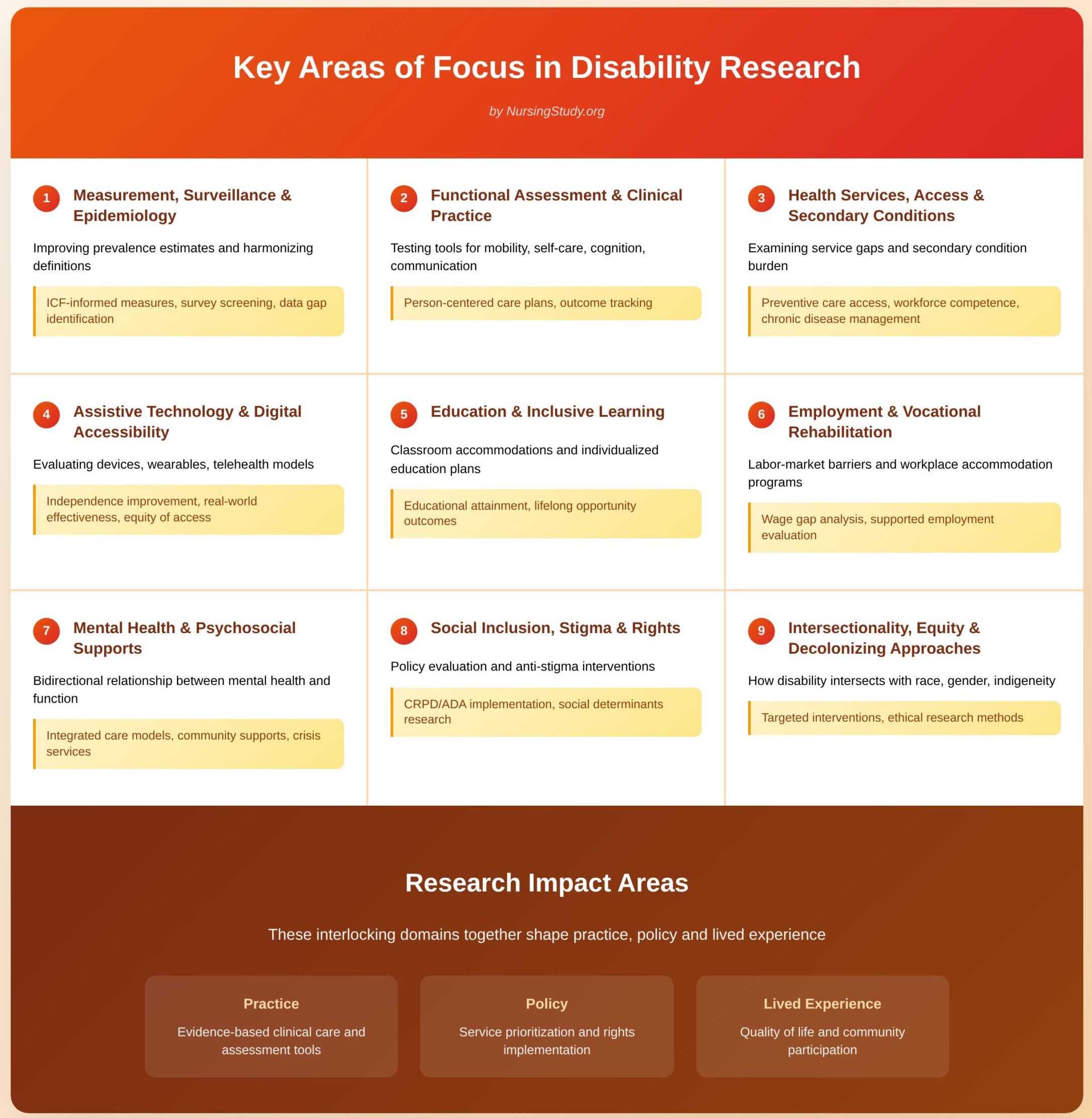

Disability research today clusters around several interlocking domains that together shape practice, policy and lived experience.

1. Measurement, surveillance and epidemiology. Work to improve prevalence estimates, harmonize definitions (e.g., ICF-informed functional measures versus survey screening items), and fill data gaps remains foundational because what we measure determines who is counted and which services are prioritized.

2. Functional assessment & clinical practice. Research tests and refines tools that assess mobility, self-care, cognition, communication and participation so clinicians (including nurses and physiotherapists) can make person-centred care plans and track outcomes.

3. Health services, access and secondary conditions. Studies examine service gaps (preventive care, rehabilitation, accessible communication), workforce competence, and the burden of secondary conditions (pain, pressure injuries, chronic disease) that compound disability.

4. Assistive technology and digital accessibility. Evaluation of assistive devices, wearables, telehealth models, and the equity of access to these technologies has become central—both for improving independence and for testing real-world effectiveness.

5. Education and inclusive learning. Research on classroom accommodations, individualized education plans, and outcomes for students with disabilities links clinical assessment to educational attainment and lifelong opportunity.

6. Employment, vocational rehabilitation and economic participation. Studies document labour-market barriers, wage gaps, and evaluate supported employment or workplace accommodation programs (see below).

7. Mental health and psychosocial supports. The bidirectional relationship between mental health and functional limitation drives research on integrated care models, community supports, and crisis services.

8. Social inclusion, stigma, and rights. Policy evaluation (CRPD/ADA), anti-stigma interventions, and research on social determinants (poverty, housing, transport) are central to translating rights into participation.

9. Intersectionality, equity and decolonizing approaches. Inquiry into how disability intersects with race, gender, indigeneity and socioeconomic status shapes targeted interventions and more ethical research methods.

How Do Mental Health Issues Relate to Disability?

Mental-health conditions and functional disability have a complex, often bidirectional relationship:

- Higher prevalence and greater distress. Population studies show adults who experience functional limitations report higher rates of frequent mental distress and common mental disorders than those without limitations; this is driven by social isolation, unmet health needs, discrimination and barriers to care.

- Mental illness as a source of disability. Conditions such as major depression, bipolar disorder or schizophrenia can themselves be disabling when they limit daily activities, employment or social participation—thus qualifying as psychosocial disabilities in research and policy.

- Comorbidity and care fragmentation. People with intellectual disabilities frequently experience under-recognised mental-health needs; conversely, people with chronic physical impairments face higher risks of depression and anxiety. This comorbidity increases complexity for assessment and care planning and calls for integrated nursing and mental-health approaches.

Practice example (nursing assessment): a nurse performing a comprehensive physical assessment on a patient after a stroke should routinely incorporate brief mental-health screening (validated tools or observational prompts tailored to cognition), because untreated depression will impair rehabilitation participation and functional recovery.

What Is the Impact of Disability on Employment Opportunities?

Research consistently shows that people who experience functional limitations face persistent labour-market disadvantage:

- Lower participation and a measurable wage gap. International analyses report lower labour-force participation rates and, where employed, average wage penalties for people with disabilities. Recent ILO analyses document both lower employment rates and a meaningful “disability wage gap.”

- Barriers are structural, not individual. Inaccessible workplaces, poorly implemented accommodations, employer attitudes, and mismatches between education/training and job design are primary drivers of unemployment or underemployment among disabled candidates. Policy protections (e.g., anti-discrimination laws) help but are insufficient without enforcement and proactive accommodation practices.

- Evidence on solutions. Supported employment, job carving, workplace adjustments, and employer-focused interventions (training, consultation) show promise in trials and programme evaluations—but outcomes vary by context and require employer buy-in plus tailored supports.

Example (return-to-work pathway): For a nurse returning after a spinal-injury rehabilitation, a coordinated plan involving occupational health, workplace modification (adjustable workstation), phased hours, and an on-site ergonomic assessment increases sustained return-to-work compared with ad hoc approaches.

How Does Accessibility Affect Quality of Life for Individuals with Disabilities?

Accessibility—physical, digital, communicative and attitudinal—directly shapes participation and well-being.

- Link between accessibility and QOL. Systematic work on quality of life in developmental and other disabilities shows that environmental supports (transport, housing adaptations, accessible education and workplaces) correlate with improved participation, mental wellbeing and life satisfaction. Lack of access amplifies isolation and economic marginalization.

- Multiple environments matter. Accessibility in the clinic (ramps, exam tables that lower, accessible communication), the school (assistive tech, captioning), the workplace, and the home all combine to determine daily functioning. Small barriers (e.g., inaccessible appointment booking systems) can cascade into missed care and poorer outcomes.

Practice vignette: A visually impaired university student gains measurable improvement in academic performance and wellbeing when the campus provides screen-reader friendly LMS content, captioned lectures, and a course-level accommodation plan—demonstrating how digital accessibility links directly to quality of life and opportunity.

What Are the Effects of Policy Changes on Disability Rights?

Policy has a demonstrable, though uneven, impact—both enabling and revealing ongoing gaps.

- Legal frameworks change the terrain. Instruments like the CRPD have reframed disability as a rights-based issue and driven national commitments to inclusion, accessible services and nondiscrimination; evaluations find important advances in law and policy adoption but variable implementation on the ground.

- Implementation gaps persist. Research into long-running civil-rights legislation (e.g., the ADA) highlights improved access in some domains but persistent inequities in health care, transport and employment—often because regulations lack enforcement, funding or provider training.

- Policy as an intervention to test. Disability-focused research increasingly treats policy changes (telehealth expansion, school inclusion mandates, accessible procurement rules) as natural experiments: researchers measure whether legal changes translate into quantifiable improvements in access, employment, education and health outcomes. Recent reviews urge stronger monitoring, participatory implementation and data systems that disaggregate results by intersecting identities.

Example: COVID-19–era expansions of telehealth and remote work created a real-world test of flexible access. Early evaluations show telehealth lowered some barriers for people with mobility limitations, but also highlighted digital divides that left others behind—emphasizing that policy gains must be paired with digital-inclusion efforts.

What Methods Are Used in Disability Research?

Disability research employs a wide methodological spectrum, reflecting not only the heterogeneity of disability topics but also the need to capture both measurable outcomes and the nuanced lived experiences of people with disabilities. No single approach can fully address the complexity of disability in society, which encompasses clinical, educational, social, and policy domains. Researchers therefore rely on a combination of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods designs, each offering distinct strengths and limitations.

Qualitative methods

Qualitative approaches are central to inclusive disability studies because they allow researchers to document and interpret the voices of individuals with disabilities in their own words. They are particularly effective for exploring:

- Subjective experiences and identity formation. Through interviews or focus groups, researchers can uncover how stigma, assistive technology, or access to health services shapes everyday life. For example, a study of older people with mobility impairments might reveal how inaccessible public transport restricts social interaction despite the presence of formal accessibility policies.

- Cultural and institutional meanings. Ethnographic observation in schools, workplaces, or healthcare facilities can expose how institutional practices either enable or hinder disability inclusion.

- Hidden barriers. Narrative inquiry may bring to light subtle forms of ableism or negative attitudes that are often invisible in numerical surveys.

By centering disabled individuals as experts of their own experience, qualitative research challenges dominant medicalized models of disability and highlights the social determinants of participation, access, and equality.

Quantitative methods

Quantitative research provides the statistical backbone of disability studies, making it possible to track prevalence, outcomes, and disparities across large populations. Its contributions include:

- Epidemiological surveillance. Population-based surveys estimate how many individuals live with intellectual disabilities, physical disabilities, or sensory impairments, informing policy and funding priorities.

- Outcome evaluation. Randomized controlled trials can test whether new rehabilitation programs, assistive technologies, or education programs improve functional status, employment, or quality of life for people with disabilities.

- Predictive modelling. Statistical analyses help identify risk factors (such as poverty, gender, or comorbidity) that predict negative outcomes like unemployment or poor health, guiding targeted interventions.

- Policy assessment. Large datasets allow researchers to evaluate whether disability rights legislation—such as the Americans with Disabilities Act—has translated into measurable improvements in access to services or employment rates.

Quantitative studies are therefore critical for demonstrating systemic inequities, providing a strong evidence base for advocacy, and ensuring accountability in disability inclusion strategies.

Mixed-methods approaches

Mixed-methods research integrates the depth of qualitative data with the breadth of quantitative evidence, offering a comprehensive view of disability issues. This approach is increasingly valued in the research community because it acknowledges that disability is both a measurable phenomenon (e.g., functional limitation, employment rates) and a lived experience shaped by social interaction and policy contexts.

- Sequential designs might begin with surveys of students with disabilities to quantify barriers in education, followed by interviews to explore the meaning behind those barriers.

- Concurrent designs can integrate ethnographic observations with clinical outcome measures to create a holistic picture of disability and health.

- Transformative designs are explicitly guided by disability rights frameworks, embedding participation of disabled individuals throughout the research process and ensuring findings support social justice goals.

For example, a study on access to healthcare for visually impaired patients could combine quantitative data on appointment attendance and treatment outcomes with qualitative interviews that reveal the communication barriers patients face in navigating hospital systems.

Towards inclusive and responsive research

This methodological diversity reflects broader calls within inclusive disability studies to value multiple ways of knowing and to reject one-size-fits-all approaches. Rigorous disability research is not only about counting prevalence or testing interventions; it is also about amplifying voices, addressing stigma, and shaping policies that promote equal access on an equal basis with others. By integrating methods, researchers ensure their findings are both evidence-based and responsive to the lived realities of individuals with disabilities—whether in the clinic, classroom, workplace, or community.

How Do Qualitative Methods Enhance Understanding of Disability?

Qualitative methods provide a powerful way to explore the subjective and relational aspects of disability that numbers alone cannot capture. Disability is not only a matter of impairment or functional limitation; it is deeply embedded in social contexts, institutional practices, and individual identities.

- Exploring lived experiences. In-depth interviews with people with intellectual disabilities or students with disabilities can reveal how everyday interactions with teachers, healthcare providers, or employers affect self-esteem and opportunities. For example, qualitative research with children with disabilities may uncover how subtle negative attitudes in school environments shape participation even when official policies promote inclusion.

- Capturing cultural meaning. Ethnographic studies in hospitals or community centers allow researchers to analyse how organizational culture influences the treatment of disabled individuals. Observing how nurses assess patients with physical or mental impairments can uncover both good practices and areas where ableism is unintentionally reinforced.

- Documenting systemic barriers. Focus groups with women with disabilities often highlight intersectional challenges such as reproductive health access, which remain overlooked in traditional disability research. Similarly, research with visually impaired students may reveal how inaccessible course materials hinder learning, even when assistive tools are available.

- Advancing inclusive research practice. By using participatory action research, disabled people are not just subjects but co-researchers, shaping research questions and data collection. This aligns with rights-based approaches, ensuring that disability research topics are rooted in lived realities rather than imposed frameworks.

Qualitative inquiry thus amplifies marginalized voices, exposes the social and institutional dimensions of disability, and generates insights crucial for designing inclusive education programs, healthcare services, and policies.

What Role Do Quantitative Methods Play in Disability Studies?

Quantitative methods are indispensable in disability research because they provide systematic, generalizable evidence to guide policy, service design, and advocacy. While qualitative work reveals depth, quantitative approaches give scope, allowing researchers to answer large-scale research questions about prevalence, disparities, and outcomes.

- Measuring prevalence and trends. Population surveys conducted by agencies such as the CDC or WHO quantify how many individuals experience physical disabilities, learning disabilities, or psychosocial conditions. This data helps governments estimate resource needs and monitor whether disability inclusion strategies are achieving progress.

- Identifying predictors and disparities. Statistical analyses reveal patterns, such as the higher risk of unemployment faced by people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, or the elevated mental-health challenges reported by individuals with physical or sensory impairments. For instance, regression models can show how stigma and discrimination contribute to gaps in employment or health access.

- Evaluating interventions. Randomized controlled trials test whether specific education programs improve outcomes for learners with disabilities, or whether new assistive devices reduce impairment-related barriers in daily living. Quasi-experimental designs allow evaluation of policy shifts, such as the Americans with Disabilities Act, by comparing outcomes before and after implementation.

- Standardizing assessment tools. Quantitative research validates instruments that nurses and allied health professionals use to assess functional ability, quality of life for people with disabilities, or attitudes towards inclusion. Psychometric testing ensures these tools are reliable across diverse populations.

In short, quantitative methods provide the evidence base for disability rights, highlight inequalities in access to services, and inform sustainable development goals that emphasize equal access on an equal basis with others.

How Can Mixed-Methods Approaches Provide a Comprehensive View?

Mixed-methods research bridges the divide between qualitative depth and quantitative breadth, producing a holistic understanding of disability that neither approach can achieve alone. This is especially important in disability studies, where both statistical patterns and lived experiences are essential for meaningful analysis.

- Sequential explanatory designs. A researcher might first use survey data to show that disabled individuals have lower rates of employment compared to those without disabilities. Then, through interviews, they can explore the personal and structural reasons—such as workplace ableism or lack of accommodations—that explain the numbers.

- Concurrent triangulation. Studies can simultaneously combine focus groups with disabled children and statistical data on education outcomes. This cross-validation ensures that research findings are both credible and grounded in real-world experience.

- Transformative and participatory designs. Mixed-methods can incorporate the active participation of disabled individuals in both phases, ensuring that research aligns with the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and disability inclusion strategies.

Example: In healthcare research, a mixed-methods study might measure how many patients with cerebral palsy attend routine preventive checkups (quantitative), while also interviewing families to understand why attendance is lower (qualitative). The combined results offer both measurable evidence and contextual explanations, making recommendations more actionable.

What Challenges Exist in Disability Research?

Disability research faces a set of interrelated challenges that affect the design, conduct, validity and impact of studies. These can be grouped into methodological, access/participation, ethical/regulatory, structural (funding & capacity), and dissemination barriers.

1. Definitional & measurement challenges

- Heterogeneous definitions. Different studies use different operational definitions (diagnostic labels vs. functional measures), which makes prevalence estimates and comparisons difficult. Using the ICF (function-focused) versus diagnosis-based approaches changes who is “counted.”

- Lack of validated instruments across groups. Many assessment tools lack validation for specific populations (e.g., people with intellectual disabilities, culturally diverse groups), reducing measurement accuracy. Psychometric work is still needed to adapt scales for communication or cognitive differences.

2. Recruitment, sampling and representativeness

- Under-representation. Clinical trials and epidemiologic studies often under-sample disabled participants (especially those with complex needs or cognitive differences), limiting generalisability. Federal reviews have noted disability is often omitted from diversity metrics in clinical research.

- Sampling bias introduced by accessibility barriers. Inaccessible recruitment materials, rigid clinic hours, and physically inaccessible sites skew samples toward better-resourced or less disabled subgroups.

3. Accessibility & participation barriers

- Practical access problems (transport, site accessibility, communication supports) and digital divides constrain who can take part in remote or in-person studies. Even conference and dissemination formats can exclude disabled researchers and participants.

4. Ethical & capacity issues

- Informed consent and capacity. Assessing capacity and providing accessible consent is complex for some participants (e.g., people with intellectual disabilities). IRBs and investigators must balance protection against exclusion. Guidance exists but is inconsistently applied.

5. Stigma, mistrust and social barriers

- Stigma reduces willingness to participate. Internalized and enacted stigma—alongside prior negative experiences with services—lowers participation rates and can bias samples toward those less affected by stigma.

6. Structural and funding constraints

- Uneven funding & short project cycles. Disability research (especially community-based or participatory projects) often requires longer timelines and costs for accommodations—requirements that mismatch typical grant budgets and review priorities. Recent funding cuts and terminated grants have illustrated fragility in the field.

7. Ethical dissemination & benefit sharing

- Extractive research risk. Projects that do not involve people with lived experience risk producing findings that are irrelevant or harmful, or that fail to translate into policy and services. Participatory approaches help, but they require resources and time.

How Do Stigmas Affect Participation in Disability Research?

Stigma operates at multiple levels—individual (internalized), interpersonal (family, providers), and structural (policies, public attitudes)—and each affects research participation differently.

1. Lower recruitment and biased samples

- People who anticipate negative judgment or past discriminatory experiences may decline invitations to join studies. This reduces sample diversity and can hide the most marginalized experiences (for example, those facing intersectional disadvantages). Studies show higher levels of enacted and internalized stigma among certain groups, which correlates with lower service use and participation.

2. Data validity and reporting bias

- Stigma can affect disclosure (underreporting of mental-health symptoms, abuse, or functional needs), producing measurement error. Researchers relying only on self-report without trust-building risk underestimating problems.

3. Practical solutions to reduce stigma-related nonparticipation

- Build trust through long-term community partnership. Partner early with disability organisations, advocacy groups, and peer researchers to co-design recruitment and consent materials. Participatory programs like W-DARE demonstrate how inclusive CBPR increases both access and research quality.

- Use accessible, stigma-sensitive outreach. Plain language, easy-read formats, audio/video options, and neutral language about research aims reduce fear. Compensate time fairly and offer multiple modes of participation (home visit, remote, flexible scheduling).

- Train study staff in anti-stigma practice. Project teams should receive training in respectful language, disability rights, and cultural competence to avoid re-traumatization and to encourage sustained engagement.

- Ensure confidentiality & safe reporting routes. Clear privacy protections and options to report concerns bolster trust, particularly for sensitive topics (abuse, mental health).

What Are the Ethical Considerations in Conducting Disability Research?

Ethics in disability research combines general protections for human subjects with disability-specific concerns (consent, capacity, inclusion vs. protection, and benefit sharing). Key points and practical steps:

1. Consent, capacity assessment and supported decision-making

- Assess capacity carefully and respectfully. Capacity is decision-specific and may fluctuate; use validated, adapted capacity tools and consider communication aids (easy-read forms, pictograms, sign language). NIH and IRB guidance provide frameworks for research involving those with questionable capacity. When capacity is limited, ethically appropriate use of lawful representatives, assent, and supported decision-making should be used rather than automatic exclusion.

2. Minimising harm & maximizing benefit

- Risk/benefit calculus must consider social harms. For example, participating in a study that documents stigma could increase immediate distress; researchers must offer supports and referrals. For minimal-risk social research, inclusion rather than exclusion is usually ethically preferred if safeguards are in place. Ethical frameworks such as the Belmont Report and Declaration of Helsinki remain foundational.

3. Respect, agency and co-design

- Inclusion as an ethical imperative. Rights-based approaches (e.g., CRPD informed) call for participation of people with disabilities in research governance, design and dissemination so that the research addresses relevant needs and avoids paternalism. Participatory action research and inclusive methodologies are practical expressions of this ethic.

4. Privacy, data protection and secondary uses

- Sensitive health and identity data require robust safeguards. Researchers must plan for storage, anonymisation, and controlled access—especially where disclosure could lead to discrimination (employment, insurance). Consent forms should transparently describe data use, sharing and withdrawal procedures.

5. Equity in compensation and accessibility

- Pay fairly and remove participation costs. Budget for travel, communication supports, and reasonable accommodations (e.g., interpreters, tactile materials). Ethical review should consider whether budgets realistically fund inclusion.

Practical checklist for ethics review & investigators:

- Use accessible consent materials (easy-read / audio / video).

- Pre-specify capacity assessment and supported decision pathways.

- Budget for accommodations and participant compensation.

- Include people with lived experience on advisory boards.

- Provide referral pathways for mental-health or social needs identified during the study.

How Can Researchers Address Funding Limitations?

Funding constraints are a major barrier—especially for inclusive, participatory, longitudinal and community-based research. Practical strategies to mitigate funding gaps:

1. Diversify funding sources

- Combine federal, foundation, philanthropy and NGO funding. Government toolkits and consortiums list targeted funding streams for disability research and capacity building (e.g., national disability research programs, ACL/ICDR toolkits). Smaller foundations may fund participatory pilots that later support larger grants.

2. Build partnerships that share cost & expertise

- Collaborate with disability organisations, health systems, schools and industry. Partnering reduces unilateral costs (e.g., clinics provide space; NGOs support recruitment) and strengthens grant competitiveness by showing co-investment and community buy-in. Participatory partnerships also increase the likelihood of sustained translation into services.

3. Use phased, scalable designs

- Start with a small pilot or feasibility study and leverage results for larger funding. Funders often prefer staged approaches with preliminary data and community support. Use low-cost pilots (secondary data analysis, focus groups, rapid usability testing) to generate proof of concept.

4. Leverage existing data & secondary analyses

- Use national surveys, administrative datasets or registries to answer initial questions without the high cost of primary data collection. This can produce publishable results that justify more expensive, inclusive follow-ups.

5. Build capacity & advocate for structural change

- Invest in training early-career researchers (including people with disabilities) and in mentorship. Institutional investment increases long-term funding success. Also advocate with funders to include disability as a dimension of diversity and to create targeted funding lines (recent federal reports have urged this).

6. Design budget lines for inclusion

- Explicitly cost accommodations and participatory activities in grant proposals. Reviewers increasingly expect realistic budgets for accessibility, engagement and dissemination to affected communities. Showing costed plans for interpreters, easy-read materials, and travel strengthens proposals.

7. Community co-funding and non-traditional sources

- Crowdfunding, social enterprise models, and local government partnerships can sometimes fund pilot or implementation phases—particularly for small-scale assistive technology pilots or community programs. Use these strategically while ensuring ethical fundraising practices.

Conclusion

Disability research is a dynamic and evolving field that sits at the intersection of health, education, social justice, and human rights. Far from being a niche specialty, it addresses fundamental questions about how societies recognize, support, and empower people with disabilities to live on an equal basis with others. Throughout this discussion, it becomes clear that disability research topics must be approached not only as academic exercises but also as practical pathways to shaping inclusive education programs, improving access to services, and advancing disability rights across diverse contexts.

The field’s richness lies in its methodological breadth. Qualitative studies reveal the lived experiences of individuals with disabilities, highlighting barriers such as stigma, negative attitudes, and ableism, while also capturing stories of resilience and innovation. Quantitative research contributes the statistical evidence needed to track prevalence, evaluate interventions, and assess the impact of policy reforms like the Americans with Disabilities Act. Mixed-methods designs integrate these perspectives, ensuring that findings are both evidence-based and grounded in the lived realities of disabled individuals.

At the same time, significant challenges remain. Persistent stigma, barriers to participation, and funding limitations continue to undermine the full inclusion of disabled people in research. Ethical dilemmas—such as how to balance protection with autonomy for children with disabilities or people with intellectual disabilities—demand thoughtful, rights-based solutions. Addressing these issues requires not only better research design but also stronger partnerships with disability communities, attention to accessibility, and adequate investment in long-term, inclusive research agendas.

The current landscape also underscores the importance of intersectionality and social justice. Disability does not exist in isolation but interacts with gender, race, age, and socioeconomic status to shape distinct experiences of inequality. Whether exploring the quality of life for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, the educational needs of learners with disabilities, or the challenges faced by women with disabilities in accessing health care, research must be attuned to the multiple layers of disadvantage that influence outcomes.

Looking ahead, the future of disability research will be shaped by technological innovation, interdisciplinary collaboration, and policy advocacy. Emerging tools—ranging from assistive devices to digital data collection platforms—offer opportunities to enhance both participation and analysis. Cross-sector partnerships between health professionals, educators, policymakers, and the research community can generate more sustainable solutions aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals and broader disability inclusion strategies. Above all, centering the voices and experiences of disabled individuals ensures that research outcomes translate into meaningful change, supporting equal access, improved quality of life, and the dismantling of barriers that continue to exclude.

Ultimately, disability research is not just about generating knowledge; it is about transforming systems, advancing equity, and affirming the rights of persons with disabilities as full and active members of society. By integrating rigorous methodologies with inclusive practices, researchers can contribute to a world where social inclusion, equal opportunity, and respect for diversity are more than aspirational goals—they are lived realities for children and adults with disabilities worldwide.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the current topics that are good for research?

Current disability research topics include accessibility in digital environments, employment opportunities for individuals with disabilities, inclusive education programs, the impact of the Americans with Disabilities Act on daily life, assistive technology innovations, mental health and stigma, healthcare access for disabled individuals, disability and COVID-19, and intersectionality in disability studies.

What are the challenges faced by persons with disabilities?

People with disabilities often face barriers such as stigma and discrimination, limited access to services, unequal employment opportunities, inadequate education programs, inaccessible environments, negative attitudes in society, poverty, and limited participation in decision-making. They may also encounter challenges in healthcare, transportation, and social interaction, all of which reduce quality of life.

What are 21 types of disabilities?

The main types of disabilities (often overlapping) include:

- Physical disabilities

- Mobility impairments

- Spinal cord injury

- Limb loss/amputation

- Cerebral palsy

- Muscular dystrophy

- Multiple sclerosis

- Sensory disabilities

- Vision impairment

- Hearing impairment

- Speech/communication disabilities

- Intellectual disabilities

- Developmental disabilities

- Learning disabilities (dyslexia, dyscalculia, dysgraphia)

- Autism spectrum disorders

- Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- Psychosocial/mental-health disabilities (depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder)

- Traumatic brain injury

- Chronic illnesses considered disabling (e.g., epilepsy, diabetes complications)

- Age-related disabilities (e.g., dementia, frailty)

- Invisible disabilities (pain, chronic fatigue, etc.)

What are some good action research topics?

Examples of action research topics include:

- Strategies to improve inclusion of students with disabilities in mainstream classrooms.

- Reducing stigma and discrimination in healthcare settings.

- Enhancing accessibility for visually impaired students using assistive technology.

- Improving employment readiness programs for people with intellectual disabilities.

- Addressing barriers faced by women with disabilities in maternal healthcare.

- Designing community-based interventions for disabled children and adults.

- Evaluating the effectiveness of inclusive education policies in reducing negative attitudes.